Most people know the play Pygmalion in its musical comedy version, My Fair Lady.

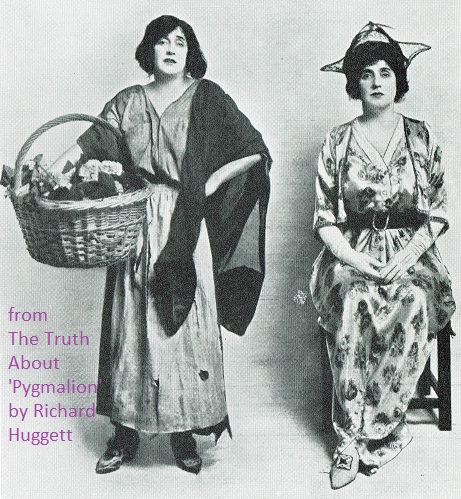

From the jacket of Huggett’s book, The Truth About Pygmalion. Left, Sir Herbert Beerbom Tree as Henry Higgins; Right, Mrs. Patrick Campbell as Eliza Doolittle.

George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion first opened in London in April, 1914. There are lots of photos of this production and of the original costumes.

1914 photos of Mrs. Pat as Eliza Doolittle. She was wearing the costume on the right (in Act III) when Eliza shocked London by uttering the phrase, “not bloody likely!”

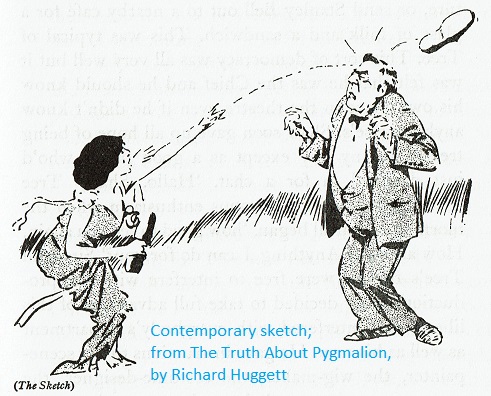

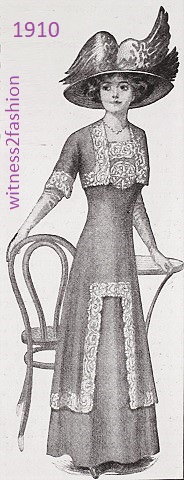

Contemporary cartoons show Eliza wearing a feathered hat more like this one with that printed suit from Act III. Delineator, January 1914

Shaw directed the play himself; the stars were Herbert Beerbohm Tree (a successful actor-producer who owned the theatre where Pygmalion opened,) and Mrs. Patrick Campbell, known as “Mrs. Pat” (or, to Shaw, who was attracted to her, “Stella.”) A very entertaining account of this production is The Truth About Pygmalion, by Richard Huggett. Three massive egos were at work; at 49, the leading lady was much too old to be playing young Eliza Doolittle, which led to insecurity and bad temper; as Henry Higgins, Beerbom Tree hadn’t mastered his lines, so he pinned notes to the backs of furniture all over the set; and since both Shaw and Mrs. Pat were famous wits, the pre-production discussions and rehearsals were rather amusing [if you weren’t involved!] This 2004 article cites some of the backstage details (but does not mention Huggett’s book.) For example, Tree (and audiences ever since) expected a romantic ending for Eliza and Higgins. Shaw, writer and director, was adamant that his play did not end that way.

As Samantha Ellis wrote in The Guardian: ‘…Shaw returned for the play’s 100th performance, but was horrified to find that Tree had changed the ending; Higgins now threw Eliza a bouquet as the curtain fell, presaging their marriage. Now that [Shaw’s] affair with Campbell was over, the romantic ending was particularly galling. “My ending makes money; you ought to be grateful,” scrawled Tree. “Your ending is damnable; you ought to be shot,” snarled Shaw.’ ***

At a time when Shaw and Tree were barely speaking, Shaw sent him a long letter filled with directorial suggestions. Tree wrote, “I will not go so far as to say that all people who write letters of more than eight pages are mad, but it is a curious fact that all madmen write letters of more than eight pages.” Tree was not a bystander in the battle of wits.

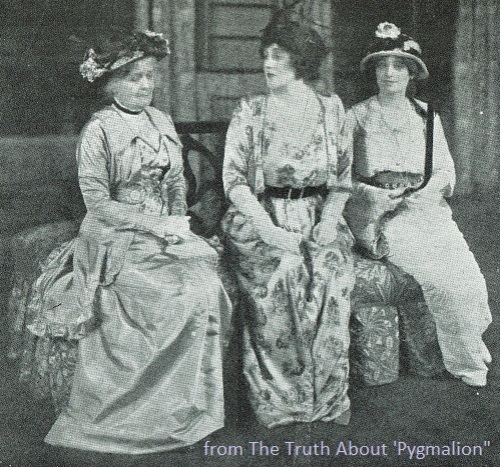

Act III, making small-talk: Eliza (carefully pronouncing her ‘aitches’) is telling Mrs. Eynesford-Hill (left) and her daughter (right) about her suspicions that her gin-drinking aunt was “done in.”

In 2014, a century after that first night, the Guardian newspaper ran a 100th anniversary article showing photos from many productions. Click here.  This photo is from the original 1914 production; it’s interesting because Shaw specified that Eliza is wearing a Japanese kimono when her father comes to call. (He’s actually hoping to extort money from Professor Higgins.) Her appearance in a kimono leads her father to assume that she is Higgins’ mistress. The shocking, undressed, quality of Mrs. Patrick Campbell’s luxurious brocade costume is not obvious from the script:

This photo is from the original 1914 production; it’s interesting because Shaw specified that Eliza is wearing a Japanese kimono when her father comes to call. (He’s actually hoping to extort money from Professor Higgins.) Her appearance in a kimono leads her father to assume that she is Higgins’ mistress. The shocking, undressed, quality of Mrs. Patrick Campbell’s luxurious brocade costume is not obvious from the script:

Shaw wrote:

[(Doolittle) hurries to the door, anxious to get away with his booty. When he opens it he is confronted with a dainty and exquisitely clean young Japanese lady in a simple blue cotton kimono printed cunningly with small white jasmine blossoms. Mrs. Pearce is with her. He gets out of her way deferentially and apologizes]. Beg pardon, miss.

THE JAPANESE LADY. Garn! Don’t you know your own daughter?

DOOLITTLE [exclaiming] Bly me! it’s Eliza!

The photo shows that Mrs. Pat’s costume was not quite the prim cotton kimono which Shaw described!

Two original color sketches for Mrs. Pat’s Eliza Doolittle costumes are in the collection of the V&A museum. They were made by/designed by Elizabeth Handley Seymour. Click here for a color sketch of that Act III [yellow] suit, and here for Eliza’s Act V costume, adapted from a design by Poiret.)

Photographs of Eliza’s first “flower girl” costume could be purchased by fans; this is a costume from later in the play.

Eliza’s evening gown is suggested in this sketch:

Eliza, in evening dress, throws a slipper at Higgins. In rehearsal, Mrs. Pat accidentally hit him. Tree had forgotten she would throw a slipper at him, and burst into tears.

Butterick evening costume made from waist (bodice) 6688 and skirt 6689. Delineator, Feb. 1914.

If you are interested in the long relationship between Shaw and Mrs. Pat, a “two-hander” play called Dear Liar, by Jerome Kilty, is based upon the letters exchanged by George Bernard Shaw and Mrs. Pat at the time when he was in love with her, and for decades after. (She had surprised him painfully by getting married to someone else two nights before Pygmalion opened.) There is a good review of a 1981 Hallmark TV production here.

There are many anecdotes about Mrs. Pat; when she was young, beautiful, and at the height of her success, a playwright who wanted her to appear in his next production made the mistake of insisting that he read his entire script aloud to her. He had not lost all the traces of his Cockney accent. Mrs Pat listened for over two hours. When he finished and asked her opinion of the play, she said, “It’s very long… even without the ‘aitches.’ ”

When she was old and broke, she was devoted to her pet dogs, which she carried everywhere with her. When one of them left a mess on the floor of a taxi, she assumed her most impressive demeanor and said, in a voice that had once thrilled thousands, “It was me!”

Sexually liberated, she is credited with saying (about a notorious divorce case,) “It doesn’t matter what you do [in the bedroom] as long as you don’t do it in the street and frighten the horses.” When asked why she married George Cornwallis-West in 1914, she said, “He’s six foot four — and everything in proportion.” There is plenty of entertaining reading about Shaw, Beerbom Tree, and Mrs. Patrick Campbell.

Eliza Doolittle sold bunches of violets, like this one. Delineator, 1914.

Many people only know the musical adaptation of this play, My Fair Lady by Lerner and Lowe, which was made into a movie with famous costume designs by Cecil Beaton. Beaton was inspired by the “black Ascot” of 1910, when all of high society wore black or white in mourning for King Edward VII. (This also allowed Beaton to avoid the wide-hipped gowns of 1914.) In fact, Shaw finished his original script of Pygmalion in 1911, so setting the play (or musical) a few years earlier than 1914 is perfectly logical. In 1914 it had to look fashionably up-to-date. That’s not a problem any more!

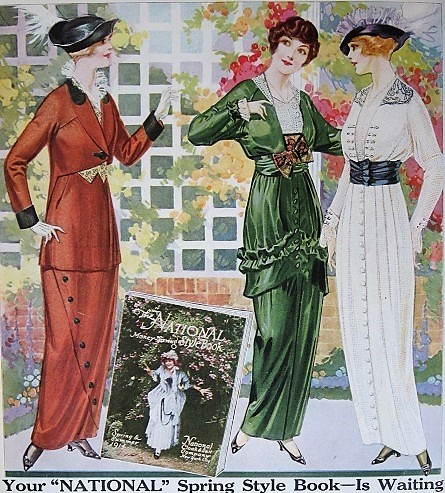

In case you are costuming either the straight play or musical version, I’ll share some inspiration from 1914, although you may prefer the styles of 1910…. It’s up to you (and the director….)

Two outfits from January, 1914. Butterick patterns from Delineator.

One of Mrs. Pat’s Pygmalion costumes had a dark mid-section rather like this one:

The dark “sash” at the waist would flatter a portly figure like Mrs. Pat’s. Butterick coat 667 with skirt 6664, February 1914.

A range of styles from March 1914; National Catalog. (The skirt on the green one? Arrrrgh!)

Below are real fashion photos from 1914. They may make you think twice about those 1914 silhouettes….

French couture fashions in Delineator, April 1914.

Dresses from 1910 are curvy — but perhaps a little stodgy…. On the other hand, those 1910 white lingerie dresses would be quite a transformation for Eliza.

Left, a lingerie dress. Butterick princess gowns “appropriate for dressy wear.” Delineator, January 1910.

1910 gowns and a suit from the National Cloak Co. catalog.

The two on the left could be Mrs. Eynesford-Hill and her daughter. Mrs. Higgins also has to show mature elegance. Butterick patterns, 1910.

In the 1992 production at London’s National Theatre (RNT,) Mrs. Higgins wore a marvelous, artsy teagown that epitomized the “Liberty” fashion reform/Arts and Crafts look (– the equivalent of being a “hippie” in the 1880s.) It made perfect sense that she could have accidentally raised a self-centered man-child like Henry Higgins. (Designer: William Dudley.) As Higgins, Alan Howard flew into tantrums like an overgrown 2-year-old. Very funny. Sadly, I can’t find that photo today.

Perhaps it’s just her pose that looks so self-assured. January 1910. Eliza could wear that skirt with a simple blouse in Act II.

This lace-trimmed ensemble is from a fabric ad: Himalaya cloth from Butterfield & Co. February 1910. Is that Eliza’s facial expression — asserting her independence — from Act V?

*** Once a play opens, the director moves on to other jobs and the stage manager is left to make sure every audience sees the same play that opening night critics saw. Probably my favorite story about the propensity of actors to “improve” the production as time goes by is: After a few weeks, the director returned to watch the play, standing quietly behind the audience. The leading man had expanded his role considerably. At intermission he received a telegram from the director: “Am watching the play from the back of the house STOP Wish you were here.”