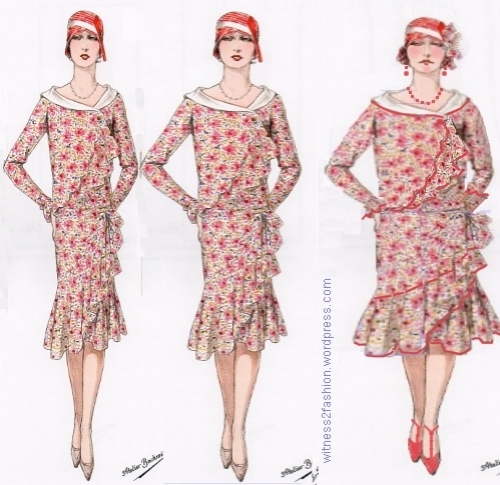

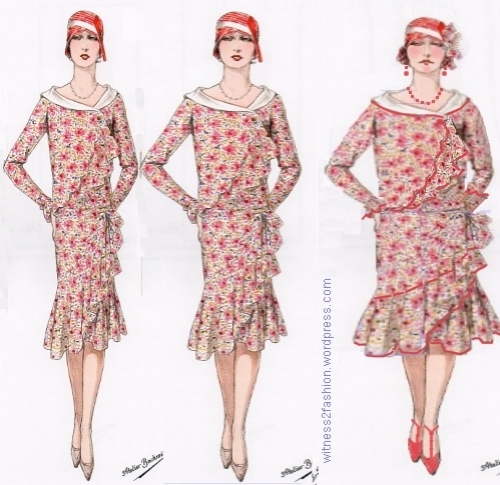

Two plates from Classic French Fashions of the Twenties, Atelier Bachwitz. A Dover Book. Sporty Styles for 1929. Images from this book are used for purposes of review only. Please Do Not Copy.

I have had hours of pleasure studying the images in this book.

My first real design job, in grad school, was a production of The Royal Family, a play about a multi-generational family of actors [any resemblance to the Barrymore family was definitely intended]. It was originally performed December 1927 through 1928. Here are the real Lionel Barrymore and his brother John acting together in the film Grand Hotel, 1932.

Lionel and John Barrymore in Grand Hotel, 1932. Image from Pinterest.

A digression: This generation of the Barrymores successfully transitioned from stage to film: Ethel as a mature actress, her brother Lionel as a character actor; and John, who was the American Hamlet of his era, was a matinee idol in the twenties and also a notoriously successful ladies’ man.

A Shakespeare student, hoping to get some insight into the characters’ motivations, once asked John Barrymore, “Did Ophelia sleep with Hamlet?”

“In my company, always,” Barrymore replied.

Ophelia (Mary Astor) and Hamlet (John Barrymore), 1925. Photo by Albin from Vanity Fair. This Ophelia did, as revealed in Mary Astor’s very frank autobiography.

Now, back to designing costumes for a play set in 1927:

My first meeting with the director was going very well; I hadn’t owned many books as a teenager, but one, which I read over and over, was Vanity Fair: A Cavalcade of the 1920s and 1930s, edited by Cleveland Amory and Frederic Bradlee. I loved the twenties, as I knew them. I “got” the references to popular culture in the play. I knew who the characters were, read “their” biographies and understood the character types. I even knew that a man who appears partially undressed in a 1927 comedy would be wearing stocking garters — good for a laugh in 1980.

I knew how a successful theatrical producer — or actress — in the twenties might be dressed.

Producer Florenz Ziegfeld and his wife, actress Billie Burke, from Vanity Fair, 1927. Photo by Steichen.

I was delighted when the director told me he didn’t want “musical comedy” costumes; he wanted real, authentic-looking 1920’s clothes — absolutely true to 1927-28. And then, just as I packed up my notes and put my hand on the doorknob, he said,

“Just don’t give me any of those dresses with the waist down around the hips.”

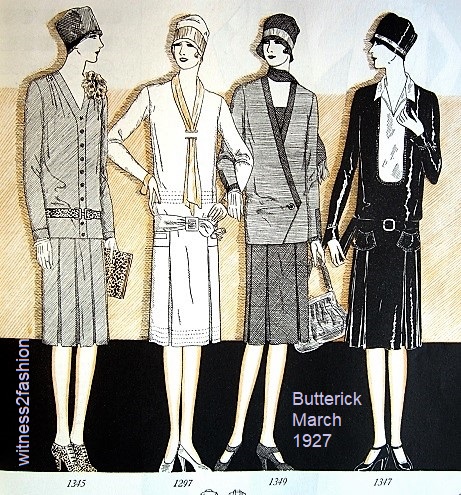

Three Hattie Carnegie outfits from July 1928. Delineator.

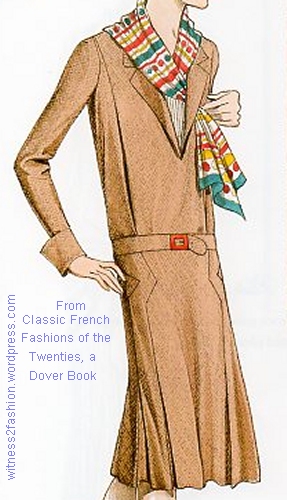

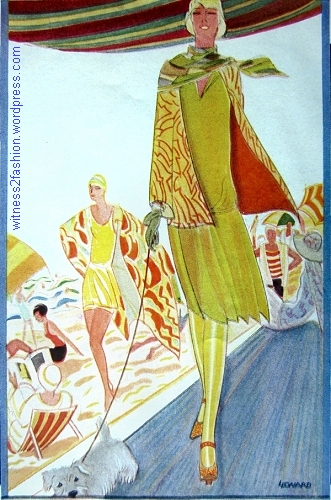

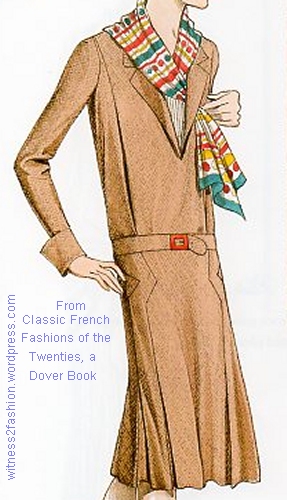

I couldn’t help thinking about this experience while looking through the beautifully illustrated collection of styles from Beaux-Arts des Modes, 1929, which is published by Dover Books as Classic French Fashions of the Twenties. The author credited is Atelier Bachwitz. (Was it a sketch studio or a magazine publisher? The Met has another Atelier Bachwitz publication.) The fashion plates, with each design given an entire page in full color, are lovely, and so detailed that you can study their construction. From sporty outfits like those white pleated dresses at the top of this post, to afternoon dresses, fabulous coats, and evening wear, you can dream about an entire 1929 wardrobe — and how you’d make it — while studying these pages.

Plate 31 from Dover’s Classic French Fashions of the Twenties. This ensemble has a 3/4 length coat to harmonize with the dress’s asymmetrical hem. The sleeve cuff echoes the pocket.

I’m glad I bought this book, just for the pleasure of analyzing lovely renderings like this one. The vertical seam lines down the back of the coat are a slenderizing touch….

…Which just goes to show that the costume designer probably studies them with a skewed viewpoint. For one thing, you are “Shopping in Character,” trying to think like the characters in the play or script, and choosing appropriate clothes for them. You think about their age (and how they feel about their age,) and their personalities. You think about what happens in the play to the woman wearing this dress. You think about her budget (the women who could afford these dresses were not shopgirls or schooteachers.) And you think about the actor’s figure, and how the audience will perceive her clothes. After all, “Costume Communicates” is a First Principle, and the audience will have a smaller style “vocabulary” than a costume historian. You try to remain true to the period, while keeping audience expectations –based on modern clothing — in mind.

I’ve shown this picture before, and asked, “If you were an actress — whose next job might depend on being shapely — which would you prefer to wear?”

These three outfits from a 1917 catalog not only express different personalities — the girl on the right seems super-feminine, compared to the less fussy clothes on the left — but only the center outfit would not make the actress look overweight to modern eyes. [It has a long, vertical jacket opening, and the belt doesn’t create a horizontal line across the semi-fitted waist.]

That problem — making the star attractive to modern eyes — is always at the back of your mind when designing for real bodies, especially when looking at research from the 1920’s. I think it’s natural to look through a book like Classic French Fashions of the Twenties searching for ways the original designers dealt with the same problem.

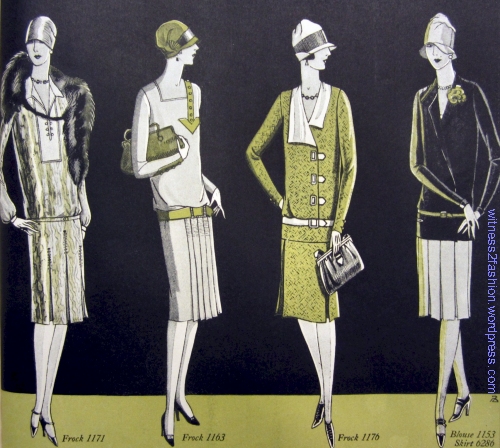

One way was to introduce vertical design lines:

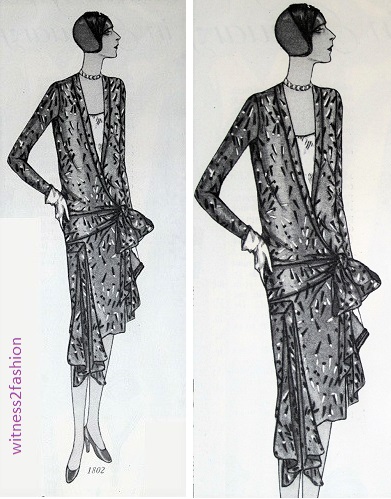

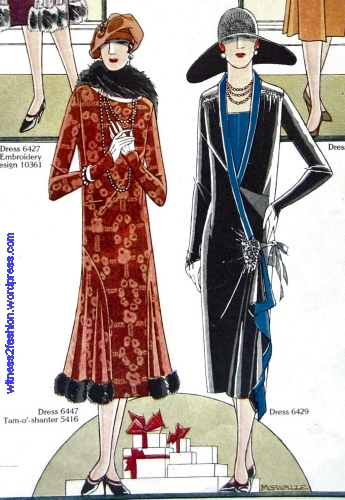

Authentic 1929 designs with strong vertical lines. From Classic French Fashions of the Twenties.

Another good idea, especially for actors and singers, is to attract attention upward, toward the face.

Plates 9 and 39 from Classic French Fashions of the Twenties. The center of interest in these dresses is close to the face, not the hip.

The seam lines on the left dress are ingenious, literally pointing toward the center of the body, away from the hip width.

“Focus on the face” is the reason we see so many bright scarves and contrasting collars on 1920’s and 1930’s clothing.

On the two dresses below, the area near the face and shoulders is much lighter than the area near the hips. Cleverly, in front the designer has avoided “cutting the body in half” with a horizontal color change at the waist or hip.

Plate 44 and plate 14 from Classic French Fashions of the Twenties. The top part of each dress is lighter than the bottom part. Again, the eye is led toward the face. The dress on the left doesn’t have to be made in red….or have such a wide buckle.

I was delighted to find this very similar dress — via Instagram (thank you, Vintage Traveler!) — from the NYUCostumeStudies site. It has a strong family resemblance to these dresses, which bridge the seams between dark and light fabric with coordinating embroidery. The evening dress from Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens belonged to etiquette maven Marjorie Merriweather Post. Their online dress collection is superb.

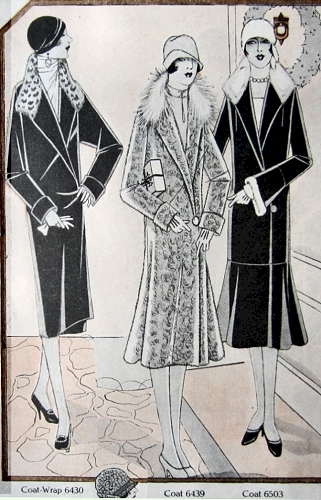

I just have to share this Art Deco coat design. It is much simpler to make than it looks.

This coat is made of “silk rep, with incrustation forming scallops. Open sleeves, shawl collar.” 1929.

“Incrustation?” Also used about other designs in the book, “incrustation” appears to be a translation meaning “applied trim.” The “scallops”, which I would call zigzags, would be absolute hell if they were seam lines. But this coat is not pieced together; the lines appear to have no structural purpose (see its back view) except, perhaps, on the collar. Again, look how tall and slender she appears in the back view. (Vertical lines….) And there is no “waist down around the hips,” either. Unfortunately, I didn’t have this book in grad school, but I did solve my problem back then by asking the director to move the date of the play to 1929! By then, some dresses had belts at the natural waist.

Another thing to keep in mind: If a dress seems too frilly, too silly, or too fattening for the leading lady, it might be perfect for another character — like the 50-ish matron who wears clothes that are too young for her, or the scatterbrained socialite who moves in a cloud of fluttering chiffon. Classic French Fashions from the Twenties has plenty of ideas that might not be right for everybody, but which may be perfect for somebody.

Three versions of a frilly chiffon dress: Left, as drawn; center, on a more realistic figure; and right, as it might look on a character who overdoes everything.

I wasted way too much time playing with that in a photo program!