Vionnet , 1936. Metropolitan Museum photos

In Part 1, I shared bits of a marvelous lecture about Vionnet, given by Sandra Ericson in 2010. I recently looked at Sandra Ericson’s site online, The Center for Pattern Design, (click here) and found that there have been many changes — she has relocated from northern California to Oregon, she now sells patterns and specialized books online, and she offers lectures and seminars all over the country. (Back in 2010, she was getting ready for a seminar/workshop on Balenciaga. See her two-day seminars. Vionnet is not her only specialty, but is the topic for a five day seminar/workshop.)

Her site says, “Each seminar and the instructor, Sandra Ericson, meet the qualifications for university level instruction for degree or non-credit fashion programs. If inclusion in an accredited program curriculum is desired, please contact us for further compliance information.”

You can also watch her free online class in patternmaking “from sketch to pattern.” ) On my computer it took a very long time to load, but a long-ago class — in grad school — when I first learned about “pattern manipulation” was one of those life-changing moments.

“The Most Expensive Gown in the World:” by Madeleine Vionnet, in a Pebco toothpaste ad. Delineator, Sept. 1931. “Though apparently simple, its classic loveliness is founded on the most intricate cutting and molding to the body lines. By courtesy of Bergdorf-Goodman.”

When Ericson lectured at the de Young museum, she said the only way she publicizes her draping workshops is via her newsletter, so please visit her website if you want to subscribe to her mailing list. (click here, then scroll down to bottom of page.)

The lecture included plenty of visual material, with slides and half-scale versions of Vionnet designs from the early 20’s through the end of the 1930’s. Obviously, it’s hard to to do her lecture justice without her slides, but Ericson also recommended some books on the life and work of Madeleine Vionnet, especially Madeleine Vionnet by Betty Kirke (available from Amazon for as little as $76). Another, Madeleine Vionnet by Pamela Golbin, is also available for $75 or so, used.

Betty Kirke also wrote a “must read” article about Vionnet for Threads Magazine, which you can read online (illustrated). It has some amazing pattern layouts!

Velvet gown by Vionnet, photographed by Edward Steichen. Advertisement in Delineator, 1925.

Also just a click away is an article in Threads Magazine which shows half-scale reproductions of Vionnet designs. To read read “Vionnet in Miniature” (click here).

Vionnet draped on half-scale mannequins so that she could see the whole design at once. (Click here to see her at work.)

(Where can you get an affordable half-scale mannequin? Ericson ingeniously makes them from My Size Barbie dolls — and sells a pattern for turning a Barbie figure into a human figure for about $13. (See it here.) The doll is not included — they cost about $60 online.

These are notes I took at Sandra Ericson’s 2010 lecture on Vionnet — any errors are mine. The patterns used for illustration are not by Vionnet, but show her influence. My drawings are pure conjecture.

What I Learned in Two Hours

Ericson divided her lecture into “6 Principles of Elegant Cutting” – “epiphanies” she had while studying Vionnet.

Vionnet as Architect: Vionnet thought of herself as an architect or geometrician. Her design goal was simplicity and integration. Integration: nothing is added that isn’t part of the whole (no trims, etc., that don’t have a function) and Simplicity: achieve the most design excellence with the least amount of “work” – that is , the fewest seams/cuts possible.

Vionnet gown photographed by Irving Penn. This dress is four rectangles, worn on the bias. Collection of Metropolitan Museum

Vionnet’s Fabrics: Ericson also gave a list of fabrics that work best for Vionnet’s approach: those that have a balanced thread count, a loose weave (not synthetic, usually), twisted yarns, less friction (so they flow over the body), less dimensional stability (seek fabrics that do NOT keep a square well) and weight: Rayon, silk, wool, crepe chiffon, georgette, twills, nets.

Anatomy and Style Lines: Vionnet stressed the importance of the geometry of the human body: Style Lines – places where the seams go – should coincide with the direction of the muscles.

Vionnet thought seams should follow the lines of our musculature. Anatomical drawing by Hugh Laidman in his book Figures/Faces; Vionnet gown photo from Metropolitan Museum.

Ericson’s Analysis of Vionnet’s Six Principles of Elegant Cutting

Principle 1: Cut geometrically. Vionnet based her cutting on circles, squares, triangles, rectangles, and especially on the quadrant (quarter) of a circle.

Vionnet often began draping with a quadrant, sometimes with the tip cut off.

Some of her early dresses were cut on the straight, seamed on the straight grain, and worn on the bias. Other gowns were formed from four identical pattern pieces, often cut as rectangles, worn on the bias. (See one by clicking here.) Sandra Ericson reproduced one and wore it: a timeless design.

This 1920’s dress is tucked on the straight grain and worn on the bias:

Vionnet dress, 1926-1927. Metropolitan Museum photo. Click image to enlarge.

Some of her most influential gowns were based on a quarter circle, slashed to create a V neckline or an armhole, shaped by triangular inserts at waist or hip. . . .

Vionnet nightgown with triangular inserts, 1930. Photos: Metropolitan Museum.

An astonishing number of 1930’s dresses are shaped by geometrical inserts which use bias stretch to achieve their fit — even these dresses from Sears.

Dresses from the Sears, Roebuck catalog, 1932.

It’s tempting to think this dress is simply a quadrant with a halter, but that was just the beginning.

Vionnet evening gown, 1936. Collection of Metropolitan Museum.

Drawing: A quadrant wrapped around the body and seamed below the waist at center back. However, Vionnet shaped her gown with a side front seam, just visible in the photo.

Principle 2: Weight creates fit and form. (Rayon double crepe and 4-ply silk crepe are recommended.) Vionnet’s dresses won’t hang properly unless there is enough weight to pull the bias fabric down over the body. The weight of the fabric will usually do this on a full-length gown, but a knee-length dress will skim and stand away from the body, unless you find a way to add weight. However, Vionnet did this by integrating the added weight into the design, not by weighting it with chain.

Chiffon gown by Vionnet, 1926. Metropolitan Museum photo. The trim weights the light chiffon.

She might use many tucks or applique to add weight on a light fabric, or fur at the hem, or a pattern of fringe.

Fringed evening gown by Vionnet. 1936. Photos: Met Museum.

Principle 3: Any part can extend – into twists, ties, folds, loops. Think of a halter dress which is one long strip of fabric, covering the bust, twisting into a ‘knot’ below the breasts, continuing around the back and returning to the front to form the sash…. The folds and twists of fabric become the ‘ornamentation.’

Vionnet evening dress and jacket, wrapped and tied. 1935. Photos: Metropolitan Museum.

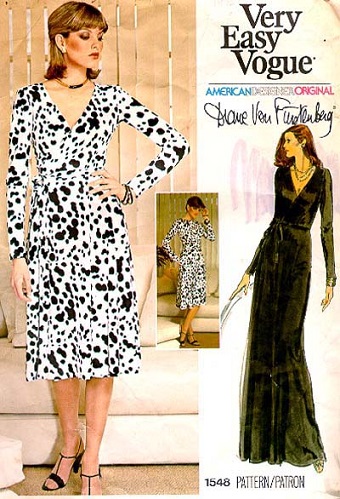

Butterick patterns 4199 (1931,) 4222 (1931,) and 4587 (1932) show the twisted fabrics pioneered by Vionnet.

Butterick 4546: “…the cape shoulders, the twisting that Vionnet has made famous, and the wrapping and tying that is very ‘last-wordish’ here now.” Delineator, June 1932.

Twisted effects: gown in a Kotex ad and a Butterick pattern, 1932.

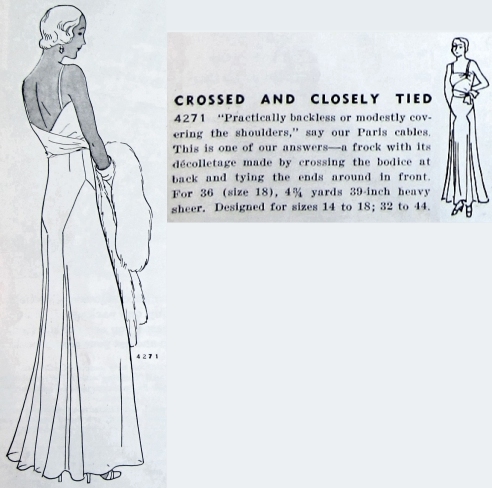

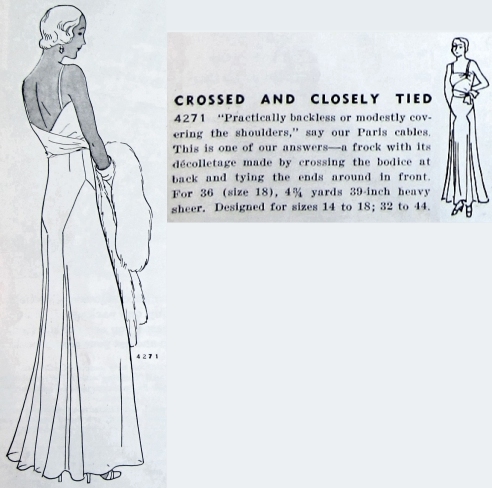

Butterick pattern 4271, “Crossed and closely tied.” January 1932. “A frock with its decolletage made by crossing the bodice at the back and tying the ends round in front.”

Note how many of these thirties gowns use panels based on quadrants in their skirts.

Principle 4: The design should integrate the closure. Vionnet liked closures to be part of the design, not added later. Often a pattern piece extends to become a draped collar, wrap behind the neck, and fall as a scarf or cape over the opening, so that there is no need for a closure.

Vionnet, 1920. The collar extends into a long scarf, whose weight helps keep the wrap bodice in place. Met Museum, NY

Betty Kirke’s pattern taken from this dress can be seen here. Another view of the dress, showing a rectangular insert in the left side, can be seen here. One Vionnet ‘suit’ which appeared to be a dress and cape was actually a single piece.

Principle 5: Decorative details create silhouette, fit, and finish. Work them on the straight grain. Examples: several rows of pintucks on a crepe day dress appear to form an X from shoulders to hips. They are stitched on the straight, but worn on the bias, and contribute to the structure of the dress.

Detail of two Vionnet dresses from the 1920’s. The fabric was tucked on the straight grain, but used on the bias. Metropolitan Museum Photos.

She also used fagoting (connecting pieces of fabric with openwork stitching ) – a square worked on the straight – which formed diamond shaped neckline and sleeve details in the (bias) finished garment. (This black silk dress from a private collection is not attributed to Vionnet, but it uses this technique.)

Black silk vintage dress with squares set on the bias and connected by fagoting.

Principle 6: Use inserts for specific shaping.

Suit, Butterick pattern 4316, Feb. 1932. The inserts at the hips, and the skirt beginning above the waist, show the influence of Vionnet.

Can you visualize the skirt of No. 4316 beginning as a straight-grain section of a circle, with straight-grain squares inserted on the bias? (The squares seem to be incorporated into the bodice.) This dress fits closely over the hips without any visible darts to shape it, although there is a bust dart in the bodice.

Think of a satin 1930’s evening gown, very full at the hem, with triangular or rectangular inserts, with the points toward the center of the body. With the sides of the rectangle on the straight grain, the panel stretches horizontally. (Click here for illustration.)

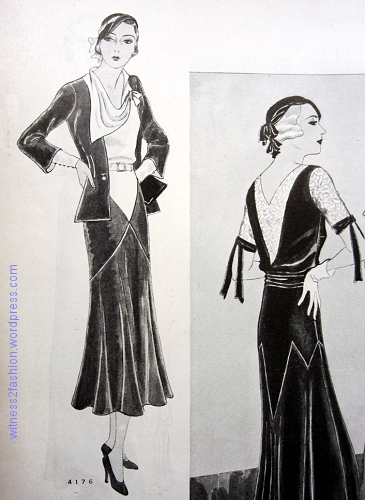

Butterick evening patterns , from 1931-32.

The dress on the right has inserts over the hips; the dress in the center seems to have a triangular insert in the bodice. Like the dress on the left, it follows Vionnet’s rule about seams following the muscles of the body. Pure genius!

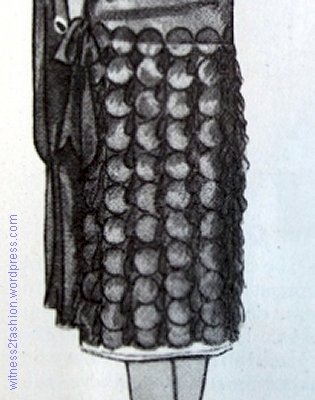

Butterick 3949. Delineator, August 1931. The skirt is based on quadrants and inserted squares used on the bias.

This Butterick pattern is clearly influenced by Vionnet. Here are some others: Butterick 3559 from 1931, Syndicate 201 from 1932, McCall 6316 from 1931, Vogue S-3453 from 1931.

Vionnet’s fabric was custom made, in widths up to 100 inches! However, you can create your own fabric by piecing straight to straight – just remember that Vionnet would want the new seams to be integral to your design!

Madeleine Vionnet never re-opened her couture house after World War II, because she knew that her body-conscious clothes were not suited to the military-influenced, shoulder-padded, boxy styles of the 40s, nor to the “New Look” with its elaborate understructures, which depended on reshaping the body rather than working with the body. However, she lived and continued teaching into her nineties, and it’s amazing to realize how much the “look” of the twenties and thirties owes to her – and how much later designers continued to incorporate her genius into the couture.

This lecture by Sandra Ericson was truly inspirational. Check out her classes, etc., at The Center for Pattern Design