A curling iron like this one was not heated with electricity. Illustration from Delineator, February 1934.

A curled hair style with ringlets over the ears, from 1838. From La Mode, in the Casey Collection.

Novelist and fashion historian Mimi Mathews has written another wonderful post about Victorian women’s hairstyles and beauty products. Click here for her latest, and then follow the links at the bottom of that post for the answer to many other “how did they do that?” questions about beauty and hair styling products from the 1800s.

In 1920, Silmerine hair curling liquid, applied with a toothbrush, was used to set curls in women’s hair.

Ad for Liquid Silmerine hair setting lotion, 1920. It could probably be used to set hair in rag curls.** The chemicals it contained varied, but some would have been cousins to the Victorian hair preparations Mimi Matthews researched.

The Silmerine ad says that “You’ll never again use the hair destroying heated iron.”

I have personal knowledge of the heated curling irons — sometimes called curling tongs — like the ones below, because my mother used them on me almost daily until I was about eight years old.

An old fashioned curling iron (in three sizes) from An Illustrated History of Hairstyles, by Marian I. Doyle.

Ad for the Lorain gas stove, 1926. The stove we had in the 1940s was similar.

This kind of curling iron didn’t plug into an electric outlet; my mother turned up the flames on one burner of the gas stove in our kitchen and stuck the metal part of the tongs into the fire for a while. (Our curling iron had wooden handles.) I was sent to the bathroom to bring her several sheets of toilet paper. I sat on a stool in the middle of the kitchen. If the curling iron curled the paper, but did not burn it, it was ready for my hair. (Our toilet paper was not soft and quilted.)

I hated the ordeal of the curling iron, and I hated having to wear a bow in my hair to school every day, too. This picture is probably 1952 or 1953 — and these curls were not in style!

Girls in the combined 2nd & 3rd grade class, Redwood City, CA, 1952-53. Only one (me) with long sausage curls. My best friend, Arleen, wasn’t fussed over; her Mom had 5 daughters to get off to school.

Once I started school and discovered that other girls — like my friend Arleen — did not have long ringlets, this daily ordeal became an ongoing battle. I hated it. But my mother’s idea of how her perfect child should look was unshakeable. We fought, I cried, I begged, but I was only allowed to leave for school once — that I remember — without being curled with that hated hot iron. (I remember skipping with joy, and then feeling the ringlets bounce into their usual shape before I had gone half a block.)

My mother frequently told me, “You have to suffer to be beautiful.” I doubt that the saying originally referred to curling irons.

[I should make it clear that I wasn’t especially afraid of getting burned, although my squirming must have made it more likely. Getting snarls combed out of my hair was worse, as my mother got increasingly exasperated with me. It was the whole, time-consuming, pointless (to me) process that I hated. At least I often got out of the house with just a brushing and a barette on the weekends.]

Once, I was allowed to stay overnight with my Uncle Mel and his beautiful wife, Irene. Aunt Irene had naturally bright red hair that fell in waves to below her waist. She coiled her thick braids on top of her head for the office, but one night Uncle Mel brought me to her house just after she had washed her hair. She was sitting on the sofa in a pale blue satin robe, brushing her red hair as it dried. It was so long she could sit on it. She told me about having her hair set with rags when she was a girl my age, and that night she offered to give me rag curl.** In the morning, when she brushed my hair, I was amazed and happy to have curls without any pain! I told my mother about this wonderful way we could stop using the curling iron. She wasn’t impressed — and I was never allowed to stay overnight with Aunt Irene again.

My mother as a teenager, with her own Mary Pickford curls.

Maybe Mary Pickford was to blame for our battles about the curling iron. And Shirley Temple.

I was an only child, born after twelve years of marriage to parents who were forty years old. My mother had had a long time to dream about the child she hoped for. I honestly don’t think it ever occurred to her that her child, and especially her daughter, would not be exactly like her — a perfectible extension of herself. She was always surprised — and saddened or angered — by every sign that I was my father’s daughter, too. I remember her disappointment when she discovered that my skin, even where the sun never touched it, was not as milky white as hers, but halfway between the whiteness of hers and the cream-white of his. And the lunch when she suddenly exclaimed, “Dammit, Charles! She’s got your mouth!” (instead of her shapely one.) My mother was so worried that I would take after his family and be taller than the boys in my class, that she lied about my age and enrolled me in first grade instead of kindergarten. I heard her tell a friend that she had decided to do it after driving past a school and seeing my older cousin in the playground with other children: “She looked like a G**-dammed giraffe!” So instead of being the youngest child in kindergarten, I was (secretly) the youngest child in first grade and in every grade until high school. It was lucky that reading came easily to me, and I had plenty of experience in being quiet and obedient, so my first teachers never realized that I was so young in other ways.

My mother had been pretty and popular; she loved to dance; so she never noticed that I was bookish and uncoordinated. I certainly never asked to be entered in a Beautiful Baby contest!

“Crowned Supreme Royal Princess Better Baby Show, Dec. 7, 1947.” I hope I didn’t wear the cape and tinsel crown to the contest! (She was sure I’d win.)

I came in second, but she made this outfit and put this picture on her Christmas cards. (The trophy said that I was “99 1/2 % perfect….)

She was certainly proud of me — or, proud of herself for having me. Relatives have told me that she treated me like a doll. She kept me dressed in frilly dresses that she washed and ironed and starched, and changed twice a day. (I got my first pair of jeans when I stayed with her mother, because Uncle Mel said Grandma was too old to cook and clean and look after a child AND do all that extra laundry.) I was completely happy at Grandma’s house. And Grandma didn’t try to turn me into Shirley Temple or Mary Pickford.

Mary Pickford shows her famous long curls in this ad for Pompeiian face cream. Delineator, November 1917.

In the 1920s, movie star Mary Pickford played little girls with long curls well into her thirties. Here she is in “Little Annie Rooney” in 1925. Pickford was born in 1892, and was only five feet tall. (She was also a formidable movie producer.) It was big news when she finally bobbed her hair in 1928, partly because she wanted to play an adult role for a change.

She would have been a megastar when my mother was a teenager. (Pickford made 51 silent movies in 1910 alone!) These pictures of hairstyles for girls from 1917 show the kind of ringlets Pickford wore, probably achieved with a curling iron. Did my mother always dream of having a child who looked like these girls?

Hair styles for girls, Ladies’ Home Journal, November 1917.

Hair in ringlets; Ladies Home Journal, November 1917.

Girl with ringlets, Ladies’ Home Journal, November 1917.

The disadvantage of curling irons was that you couldn’t curl the hair closest to your scalp — the hot iron would burn you.

My 1920s’ curling iron ringlets, done in the late 1940s.

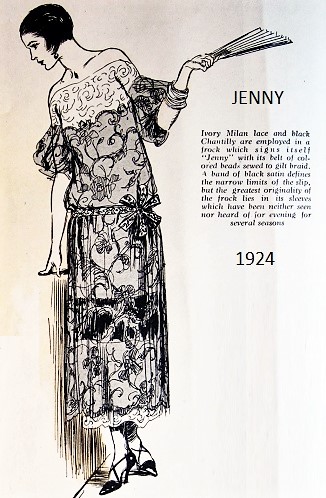

Ringlets from 1924. Delineator, May 1924.

The Pickford influence can be seen in these fashion illustrations from 1924, when my mother was twenty.

Fashion illustrations of girls, Delineator, February 1924.

Perhaps my mother formed her idea of the perfect little girl back then, although she was forty when she finally had a baby. That’s a long time, but she still had her curling iron and knew how to use it….

My curling iron curls, late 1940s.

By 1933, when my parents were married, there was a new super-star named Shirley Temple, age 5. Shirley was famous for her curls, although hers were shorter than Mary Pickford’s.

Shirley Temple in Rags to Riches, 1933. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

Shirley Temple could sing. I could sing. Shirley Temple could tap dance. I suffered through lessons in “Tap, Ballet, and Acrobatics.” Shirley Temple had a full head of curls. Click here for a picture of Shirley Temple in Curly Top (1935.) And I was given a permanent wave as soon as the beautician said I was old enough ….

These curls were the result of a permanent wave, although they needed to be kept in shape with a curling iron.

What I remember about this trip to the beauty parlor was how incredibly heavy the rollers were.

This is what getting a permanent looked like in 1932. The process was similar when I was a child in the late 1940s.

This Nestle home permanent machine had only one curling device. It took “a few” hours!

But the professional Nestle machine could curl a whole head in an hour … or three….

Professional Nestle permanent waving machine, from An Illustrated History of Hairstyles, by Marian I. Doyle.

I was fortunate that the home permanent arrived around 1950. The smell was so terrible that my mother once took me to the Saturday matinee show at the movies just to get that smell out of the house! Ah, Peter Pan in 1953! My one happy memory associated with those hated curls.

There were other, much more serious problems poisoning our relationship, but I sometimes wonder: if my mother had known that she would die when I was nine, would we still have spent morning after morning after morning fighting about my hair?

[Sorry to write such a personal post, but I mention this as something for other mothers to think about….]

** Putting your hair up in rags required some strips of clean cloth four or five inches long. You wrapped your moistened hair around a finger, slid the finger out, put the rag strip through the center of the coil, and tied it. No hairpins were needed. And you didn’t have to sleep on wire rollers, as we did in the 1960s. Sleeping on rollers should have proved that suffering doesn’t guarantee beauty!)

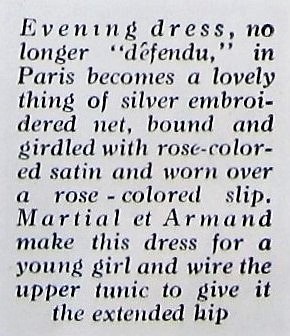

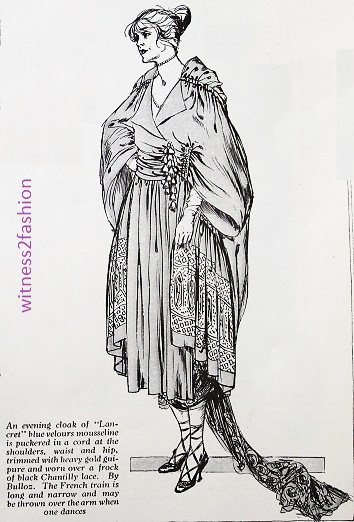

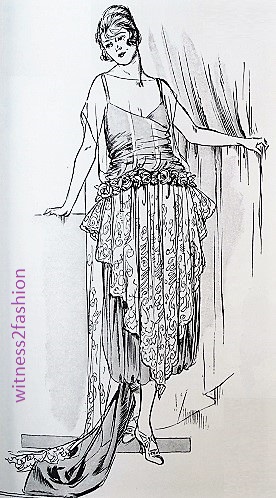

Of course, the coat to wear over a dress like this will not produce a slender silhouette, either:

Of course, the coat to wear over a dress like this will not produce a slender silhouette, either:

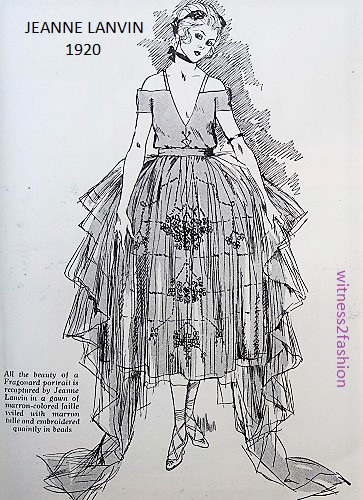

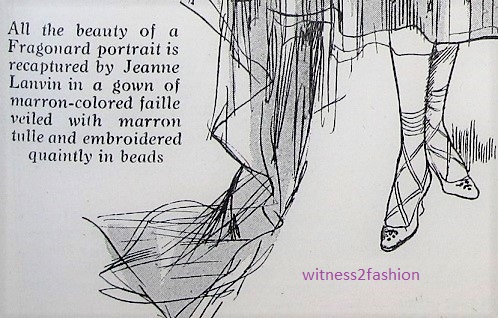

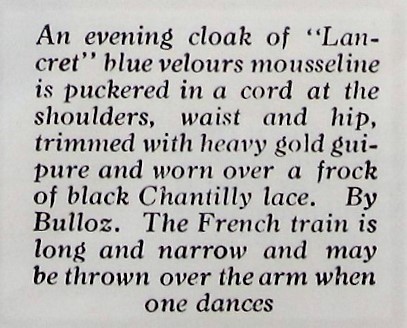

So that’s what you do with it…. Or them…. This gown has two dragging “French panels,” one of fragile lace and one of silk:

So that’s what you do with it…. Or them…. This gown has two dragging “French panels,” one of fragile lace and one of silk:

One pleasant surprise: a 1907 monthly feature illustrated by fashion photos instead of drawings!

One pleasant surprise: a 1907 monthly feature illustrated by fashion photos instead of drawings!

This photo is from the original 1914 production; it’s interesting because Shaw specified that Eliza is wearing a Japanese kimono when her father comes to call. (He’s actually hoping to extort money from Professor Higgins.) Her appearance in a kimono leads her father to assume that she is Higgins’ mistress. The shocking, undressed, quality of

This photo is from the original 1914 production; it’s interesting because Shaw specified that Eliza is wearing a Japanese kimono when her father comes to call. (He’s actually hoping to extort money from Professor Higgins.) Her appearance in a kimono leads her father to assume that she is Higgins’ mistress. The shocking, undressed, quality of