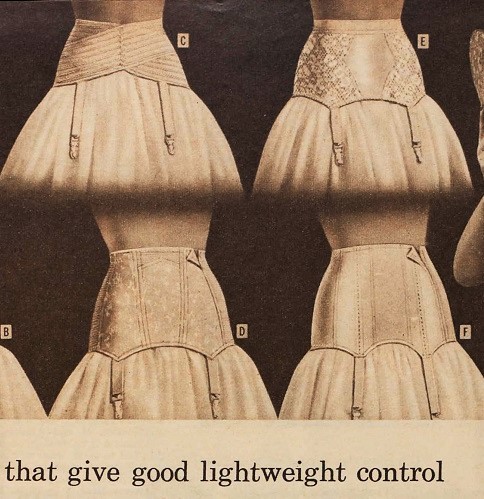

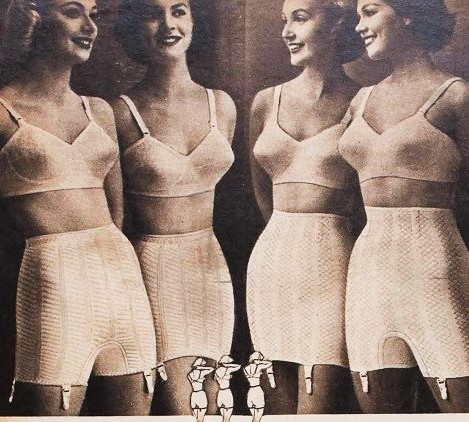

Girdles from Sears Catalog, Fall 1958.

Costume researchers of the future, given only this image, might deduce that girdles were worn on the outside of our clothes…. And that the stocking suspenders/garters were purely decorative. There was a time when manufacturers who wanted to use the same ad in “family newspapers” and in women’s magazines had to be careful how they showed women’s underwear, lest they incite lustful thoughts and corrupt the young….

I’ve mentioned before that I was a “motherless child” — raised after her death by a loving father. We managed very well, except when it came to my clothing. Luckily my Aunt Shirley, and old (female) friends of our family, and sometimes the mothers of my school friends stepped in. Mrs. Betty P., who helped me sort through my mother’s closet when my father couldn’t bear to do it, eventually told him that it was long past time for me to start wearing a bra. (Fathers are often reluctant to admit that their little girls have grown up.) She was right. She took me to a department store (along with her own daughter) to have us fitted. My first bra (age 11) was a 34 B.

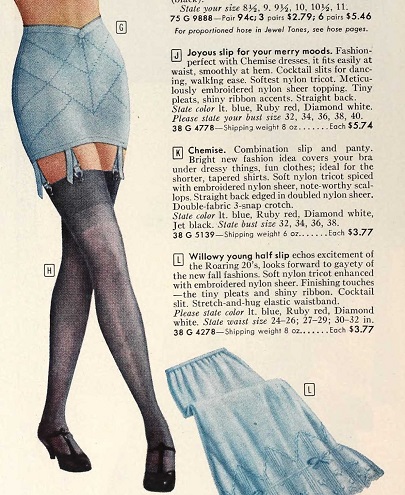

However, Betty’s daughter Janie and I used to puzzle over the lingerie ads in the backs of magazines, trying to make sense of them.

If the garters attach to your stockings, and you wear the garter belt over your bouffant petticoat…. How could that work? Sears catalog, Fall, 1958.

Full circle bouffant petticoat from Sears catalog, 1957. Janie and I knew you couldn’t bunch that up to make your garters reach your stocking tops….

This was 1957 or so — when huge crinoline petticoats were all the rage. Girls wore them in layers –preferably two bouffant petticoats at a time.

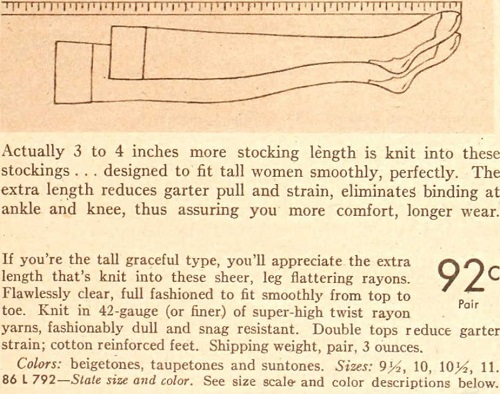

But this was also before pantyhose were available — women wore stockings held up by a garter belt, if they didn’t need “more control.”

Garter belts, 1958. Sears Fall catalog.

If you were going to wear a very fitted dress, a girdle or panty-girdle was needed so you would have a (relatively) smooth line from waist to thigh without bulges that outlined the garter belt.

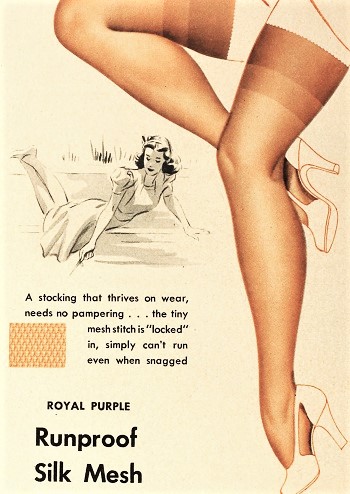

But: my 11 year-old friends and I looked at ads like this one …

“How could this work?” my 11 year old self wondered.

… and asked each other how the garter belt could reach your stocking tops, if you wore it over your bouffant petticoat?

Advertising Undies Without Offending….

In the 1920s, advertising underwear was a tricky business. What did you do about that awkward top-of-thighs area at the bottom of the corset? Should the advertiser show the long bloomers (sometimes called knickers) which most women wore?

Ladies’ bloomers (also loosely called knickers or drawers), 1925. Butterick pattern 5705.

Would a family newspaper run an ad showing underpants? Or worse, a woman’s thighs or crotch? And isn’t it possible that, however they were shown in corset ads, women sometimes wore their long underpants over their corsets, so they could be pulled down for a visit to the toilet (or outhouse, or chamberpot?)

Corsets illustrated as worn over bloomers, as shown in Sears catalogs, From Blum’s Everyday Fashions of the 1920s.

Well, 19th c. bloomers or drawers were often two separate legs, attached only at the waist. You could say Queen Victoria wore crotchless panties….

Open drawers, circa 1860, illustration from Ewing’s Fashion in Underwear. You could wear these under a corset and still answer the call of nature.

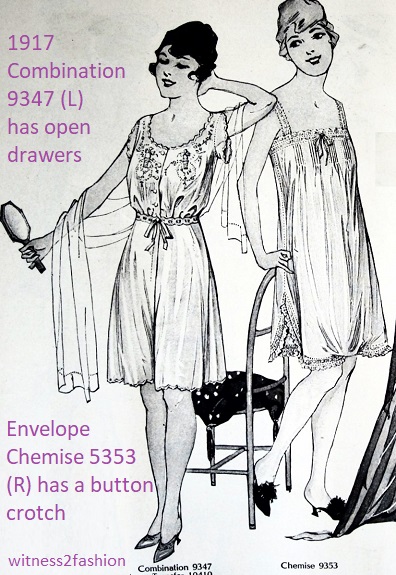

In the 20th century, many women’s underpants/drawers/knickers were made with an open crotch, or a crotch that opened with tiny buttons, so those could be worn under the corset/girdle. Awkward, but do-able.)

1917 underwear choice: open-crotched drawers (left) or a long “envelope” chemise with a button crotch. Delineator.

Pretty vintage lingerie with a button crotch.

Lingerie from Delineator, June 1924. Left, a “step-in;” right, a button crotch “chemise.”

Keep in mind that the 1930s Motion Picture Production Code in the U.S.A. had been written by men who said, “If it’s objectionable to a child, it’s objectionable, period.” (My 12th grade term paper was about movie censorship — so I’m quoting from memory.) Among other forbidden things (as reported): the inside of a woman’s thigh could never be shown in films. (An idea parodied here.) For context, here’s the article accompanying that image.

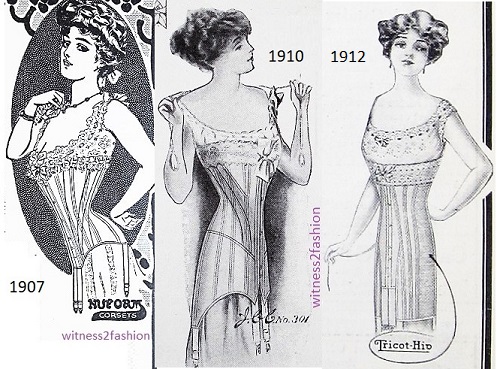

Too hot for the Motion Picture Production Code? Corset illustrations from Delineator, 1929

That nervousness about female anatomy made it difficult for advertisers show exactly how corsets and stockings were worn. Often they were shown as if the garters were purely decorative, and had nothing to do with holding up your stockings.

Message: “There are suspenders attached to our corsets.” Women would know the suspenders were for holding up stockings, but the ads didn’t show how.

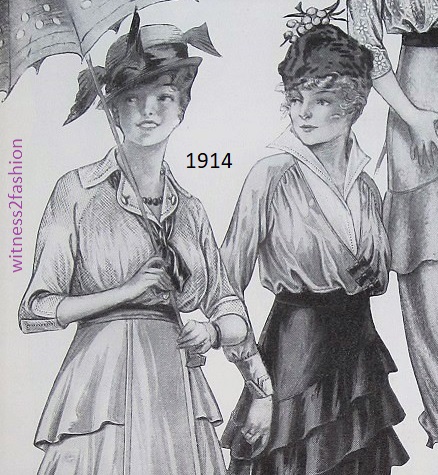

Some advertisements showed the corset superimposed on a clothed figure.

Corsets over clothing, in ads from 1912 and 1924.

Note to the future: Ordinary 20th century women did not wear their corsets over their dresses. (Although a few performers and young women with a desire to shock eventually did….)

For corset ads, a nebulous frill or draped fabric was also useful for propriety.

Sketchy lace frills or a delicate drapery avoid showing bare thighs between corset and stocking.

Some ads did show suspenders attached to stockings — but, does this mean women tucked their underwear into their stockings, as shown?

Thighs covered by long bloomers or drawers. 1926.

More voluminous undergarments tucked into stocking tops, 1922.

This company went bold — The photographer blurred out the crotch area: (Yes, photos were being altered almost as soon as they were invented.)

The area at the top of the model’s thighs has been blurred in this photo. 1926. She may have been wearing tight knit undies to start with.

Remember, in the Fifties, TV wouldn’t allow a married couple to occupy the same bed (see The I Love Lucy Show.) (And Lucille Ball, who really was expecting a child, was “Enceinte,” not “Pregnant.”)

But the 1958 Sears catalog wasn’t censoring its pages — some photos are realistic, with bare thighs appearing between girdles and stockings, as they were worn in real life. I suspect that it was up to the manufacturer to decide whether his customers were easily upset by women’s bodies…

Sorry, boys. Nothing titillating to see here!

… or not:

Models wearing bras and girdles, Sears catalog Fall 1958.

Girdle worn over bare skin, although the photo is poor quality. Inside of thigh visible! Sears catalog, 1958.

A Sears model shows how a girdle and stockings were really worn. 1958 Sears catalog.

Some slim women wore a girdle or corset with a brassiere…

Some slim women wore a girdle or corset with a brassiere…