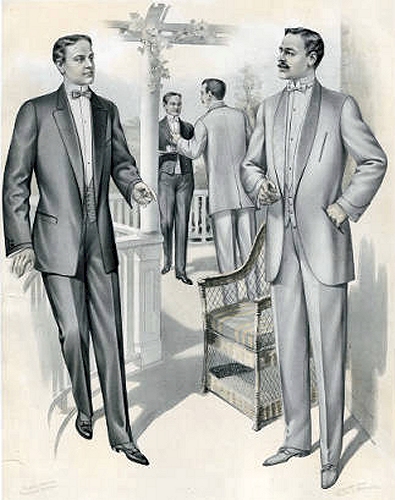

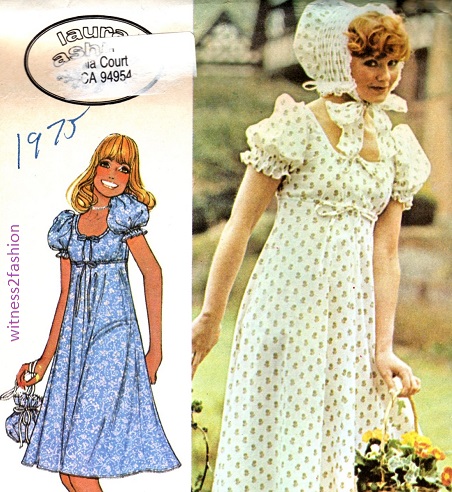

Youthful puffed sleeves, McCall’s pattern 4547 circa 1975.

Last month, I received a letter which posed some interesting questions about fashion and age:

“I would like to ask you a question: In which era did the idea develop

that women after a certain age are not supposed to wear very feminine

designs such as puffed sleeves, slim waists, lots of lace, pastel

colours or patterns with flowers? As far as I know, there have almost in

every era been ideas about what women are supposed to wear at which age.

I know designs from the 1930s and 1940s showing dresses for different

ages, with wider waists for elder ladies. But I guess this just

corresponds to larger sizes, and probably a slim lady of 70 years could

then have worn dresses with slim waists.“Anyway, it must have been an era when feminine designs were considered

attractive and youthful – perhaps the 1950s?“I am 39 years old and I cannot imagine myself not wanting to wear these

designs anymore, when I will be older….”

Well, I can start by noting that men have been making fun of older women who didn’t dress their age for a long time.

Padded bottoms from Pinterest. 18th c. cartoon.

Historically, and in cartoons and literature (mostly made by men,) older women who dress as if they were sexy young things are ridiculed. The British expression (going back at least 200 years) for such a woman is “Mutton dressed as lamb.”

(A mutton is a fully mature sheep. Mutton chops have a strong, gamy taste and smell that lamb chops do not have. On the day when Lizzie Borden did or did not murder her parents, her breakfast was cold mutton soup….)

I.e., mutton dressed as lamb is not a good thing to be.

The old woman at left is ridiculed for attempting to dress as a young woman. Note the old man with a young beauty at far right….

The blog “Americanagefashion” is devoted to the topic of clothing for American women over 55.

“Dressing your age” is a thorny problem. The goal of using makeup and dressing to express your personality is always to look like your current self at your best. If we cling to the fashions and hair and makeup styles that made us look our best when we were 18 or 25, eventually we will look ridiculous to people who are actually that age.

Do Adjust Your Makeup

The idea is NOT to look like Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

Maybelline ad, April 1929. My Aunt Dot still had a marcel wave in 1980.

In the 1980s, I used to see women on the bus who were still applying their makeup as they did in 1929.

Maybelline ad, December 1929.

Thinly penciled dark eyebrows (unrelated to hair color,) coal black eyeliner and tons of mascara (often applied badly, because they couldn’t see well without glasses [I now have this problem, myself,] dark red lips in a Cupid’s bow (extending far above their upper lip line) — these were women who were living in the past, and sadly oblivious to the changes in their faces and to the fact that “the fashion in faces” changes, too.

After teaching so many actors how to do an “age makeup” (including one actor in his 60s who was playing a 90 year old man,) I’m all too aware of the changes that come with age. Cartilage continues to grow, so old people’s noses are often larger than they once were. Our lips tend to turn in with age, making them appear thinner. The space between the nose and upper lip may seem longer, and our eyebrows get closer to our eyes. The flesh above the eyes gets puffy and sometimes sags until it touches our eyelashes. In some cases, it impairs our vision. Some of us get under-eye bags or dark areas. Uneven skin tones and blotches may appear. (And I haven’t even mentioned how hard it is to apply eye makeup to wrinkled skin….) At 75, I currently need a 15X magnifying mirror to see what I’m doing, and that means I won’t see both eyes at the same time until I finish and put on my glasses. Often, I have to do some correcting to make both eyes look symmetrical!)

In short, we have to take a fresh look at ourselves every few years, and learn to apply makeup to the face we have now, not the face we remember.

Do Rethink Your Wardrobe Occasionally

As for dressing at sixty as you dressed at 27, well, if you always preferred classic styles and modest hemlines, you’ll probably be fine. (And I do consider jeans and shirts or knit tops to be as classic as suits and dresses.) However, extreme fashions don’t always age well.

Really wide padded shoulders from Givenchy. Vogue 2303, 1989.

I had some really flattering clothes in the 1980s & early 90s. But I gained 12 lbs one year, and by the time those clothes fit again, their huge shoulder pads were laughable. I could not possibly wear them to work — not when my job was telling other people — actors — what to wear!

On the Other Hand

We’re probably lucky to be in an almost-anything-goes fashion era now, when hem length is not rigidly fixed, and mixing vintage and new is OK. Also, a woman with confidence and joie de vivre can often break the rules and look fabulous.

Twenty years ago, I was was waiting for a light to change when I saw a man and a woman walking together with their backs to me. She was wearing a black, brimmed hat (maybe crocheted?) with a black mini-dress, black hose, and knee high black suede boots. Her shining platinum blonde hair hung half-way to her waist. She was the embodiment of prosperous Hippie chic, circa 1967 -68. Suddenly she took a few dance steps, flung out her arms and twirled around. When I saw her face, I realized that her hair was not platinum. It was silver-white. She was a happy, smiling woman in her sixties. She was lively, flirtatious, and beautiful. She was breaking some of the “rules:” ‘dress your age, not younger’ and ‘don’t wear the styles that you wore when you were young.’ She was very attractive — because she was confident and joyous. Ari Seth Cohen would have photographed her if he saw her.

When and Why Dress in Black?

But to get back to the “when” part of the question, I have a lot of conjectures, and allowance for different cultural attitudes must be made. (E.g., are widows allowed to remarry in your culture? Is wearing trousers modest or immodest behavior in your country? Etc.) Also, many people are uncomfortable thinking of their parents and grandparents as sexually active….

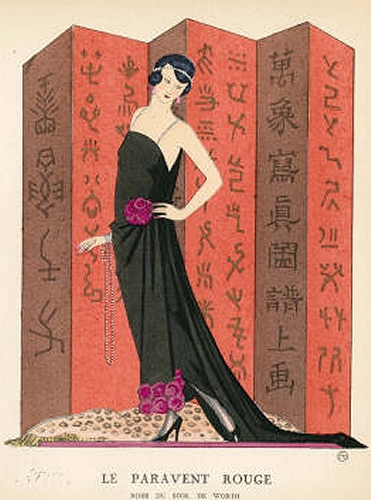

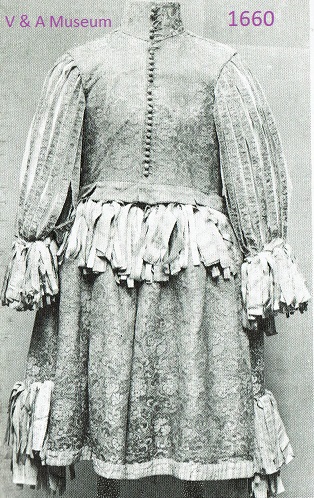

Discouraging older women from wearing pastel colors or brightly flowered textiles may go back to Victorian/Edwardian mourning customs. By the time a woman was fifty, there was a very good chance that someone in her immediate family had died within the year. Grandparents, parents, aunt & uncles, possibly her husband…. Since wearing plain, black clothing for a year after the death of a close relative was customary, some women never got out of mourning. First a grandparent, then a parent, perhaps a sister or a child, …. Consequently, many older women just wore black all the time. I attended a church-sponsored Greek Picnic in the 1960s, and all the older women were wearing black. So were some teenagers.

[Lavender was the one pastel worn by Victorians and Edwardians while transitioning from black mourning to normal dress. But “lavender and old lace” were associated with age.]

Poor women don’t have a lot of clothing, so once they dyed all their clothes black after a death, they wore them until they wore out.

As for slim waists, I don’t think older women ever padded them! However, our bodies do change, and a thickening of the waist and loss of height are common. Multiple childbirths will also change a woman’s figure. Lynn Mally at Americanagefashion.com has written a lot about “half sizes” for aging female bodies.

When you’re older and you lose weight, it may come off in unexpected places. Even though I dropped many pounds a few years ago, my formerly hourglass waist is now bigger in relation to my hips and bust than it ever was before age 60 — but I had to alter some sagging trousers in back because my butt had disappeared!

Short puffy sleeves from Woman’s Home Companion, March 1936.

As for sleeves, many older women are self-conscious about our “bat wings:” just read a bit of this blog and you’ll know why older women prefer longer sleeves to sleeves that show our upper arms. When I lost 40 pounds at age 13, my skin shrank to fit immediately. Ditto when I lost weight at 40. But after a lifetime of gaining and losing weight, we can’t expect that automatic skin shrinkage in our 60s and 70s. Now, if I want to fill out the loose skin on my arms, I need to build some muscles! So — short puffy sleeves lose their appeal. And elbow length puffy sleeves just remind me of the 1980s….

Laura Ashley pattern 8432 for McCall’s, dated 1983. Been there, done that….

Of course, sex appeal comes into this problem. I’m old, now; but I have never consciously dressed with the hope of picking up a stranger and having sex with him that night. In fact, whenever a clearly intoxicated man “hit on me” at a party or in public, I usually wondered what I had done to send the wrong signal. (I usually concluded that he must have been wearing “Beer Goggles,” because I generally wore clothes that were entirely appropriate for office work or teaching school. My rare low-cut dress was strictly for parties at friends’ houses.) So, how does a woman in her 60s or 70s dress “sexy” without seeming ridiculous? Well, I didn’t try to dress sexy in my 20s, so I’m not qualified to tell you how to do it at 75! That said, good grooming, a positive attitude, and a sincere interest in the other person are always attractive…. but those qualities attract friends. Sexual attraction may be a different problem.

A book that helped me adjust to my changing role was Ari Seth Cohen’s Advanced Style. I loved the first book he did, although by the time he made the film, some of his favorites (women with plenty of money) became stars who started to overshadow the many women who looked fabulous on a limited budget. Wearing fabulous and massive jewelry isn’t an option for most of us.

But a positive attitude doesn’t cost a cent.

In the mid-twenties the uplift brassiere was invented, which supported the breasts from the shoulder (with the combination of bra straps and an elastic band below the breasts.)

In the mid-twenties the uplift brassiere was invented, which supported the breasts from the shoulder (with the combination of bra straps and an elastic band below the breasts.)

It’s 1920 — not yet what we think of as “the Twenties,” but the “boyish” figure is already starting. (“Boyshform” was another punning brand name like “Flatter-U.”)

It’s 1920 — not yet what we think of as “the Twenties,” but the “boyish” figure is already starting. (“Boyshform” was another punning brand name like “Flatter-U.”)