Stockings and a girdle from Sears catalog for Fall 1958.

When I started high school around 1958, we wore stockings for dress-up occasions. Usually, those stockings had a seam up the back.

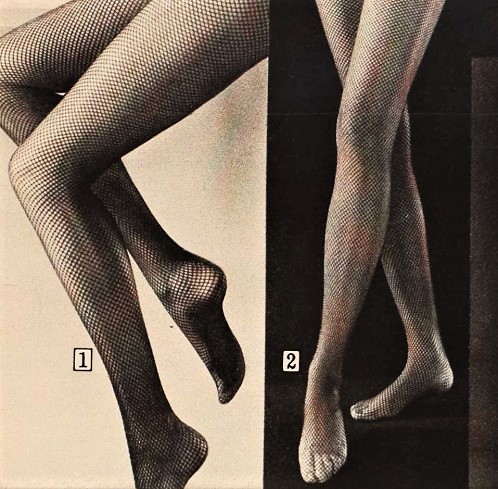

Seamed stockings from Sears, Spring 1960.

(Pantyhose became available in 1959, or so the internet tells me. Seamless nylon or rayon stockings were available — briefly — in the 1940s, but in 1958, seams were the norm for me and the adult women I knew.)

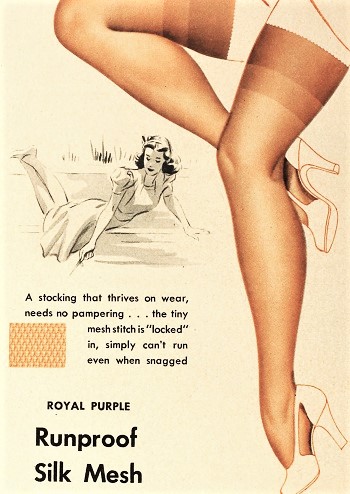

Seamless stockings advertised in Vogue, Aug. 15, 1943.

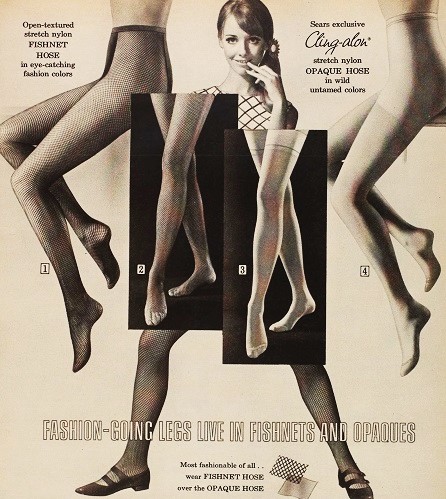

Of course, stockings are still available and worn by many women, but pantyhose have dominated the market for about 50 years now.

So, for those who never had the dubious pleasure of buying stockings in the 1950s….

A run in her stocking; Lux soap ad from October 1937. Runs looked the same in 1960: a hole with unraveled knit stocking above and below it.

At the Stocking Counter

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about stockings circa 1958 was how many choices you had to make. Faced with the stocking counter — at a department store or even a “five and dime store” — you would see rows and rows of distinctive shallow boxes, each originally holding 6 pairs of stockings. The pairs were separated by layers of tissue; you could buy one pair, incurring the barely concealed scorn of the clerk who waited on you, or two or three pairs of matching stockings (if you could afford them.) Buying the whole box was a wonderful extravagance. Stockings were so fragile that the clerks sometimes wore gloves.

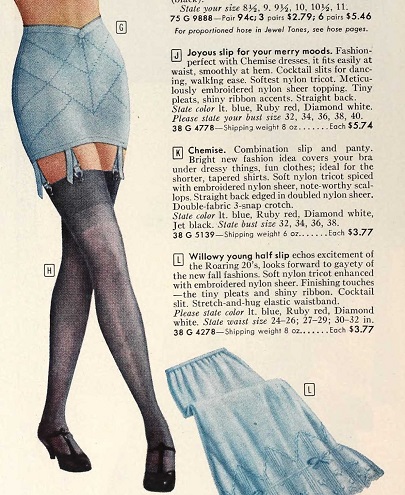

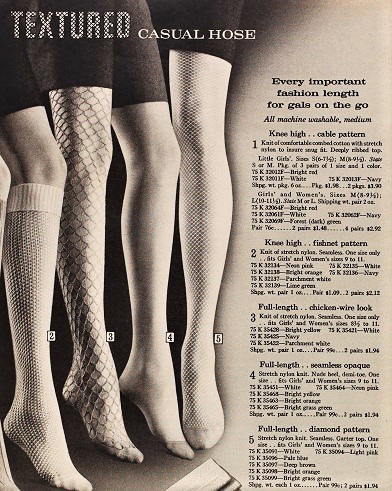

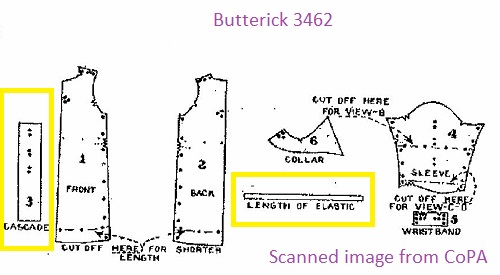

For a young teen, it was a confusing process. You needed to know your size, your “proportion,” the denier, the color, “seam or no-seam,” reinforced heel and toe or sandal foot, knit or “run stop”mesh….

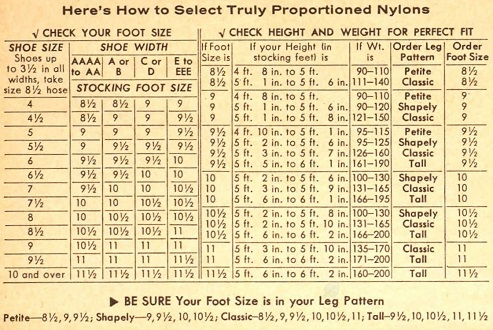

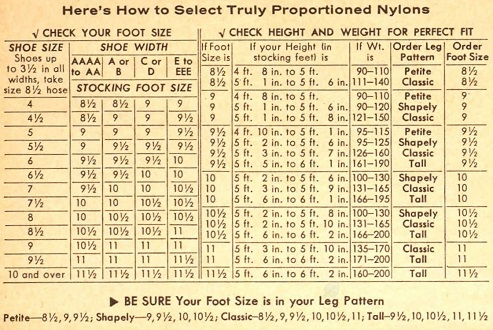

1958 stocking size chart from the Sears catalog.

“What size?” Stockings came in seven sizes. Your stocking size was related to your shoe size, but it wasn’t the same as your shoe size. [Shoes used to come in many sizes and widths, from AAAA (very narrow) to EEE (very wide.) I wore a shoe size 7 1/2, B width, with a (double) AA heel [Yes, you could buy a wide shoe size with a narrow heel, or many other variations.] As you can imagine, shoe stores had to carry almost as much stock as stocking counters.]

In 1958, your stocking size depended on your shoe size and your shoe width: shoe size 7, width B = stocking size 10.

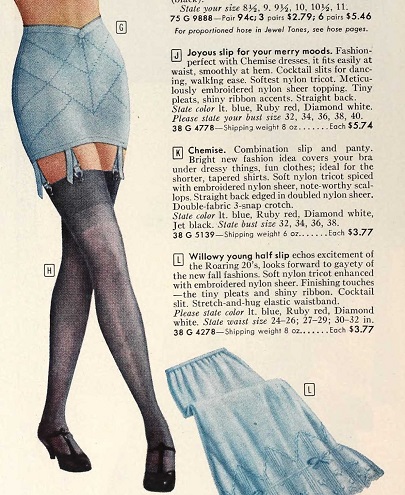

However, stockings were usually held up by garters (aka suspenders) attached to a garter belt or girdle.

Garter belts, Sears 1958. Also (more accurately) called suspender belts in England.

Top left is a girdle; all the others are panty-girdles. Notice that your stocking top would need to come quite high on the thigh to attach to these garters.

Stockings attach high on the leg, with one garter in front and one in back on this panty-girdle. Sears, 1958.

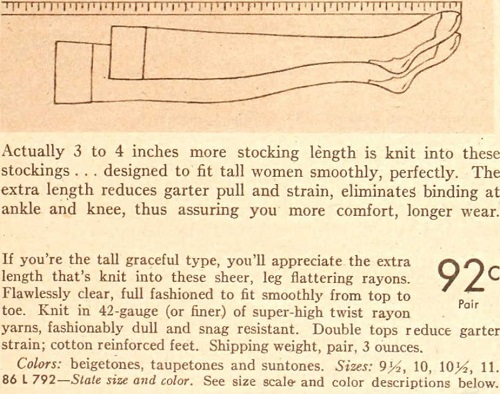

The suspender part was somewhat adjustable in length, but you had to buy stockings that were long enough to reach the garter comfortably.

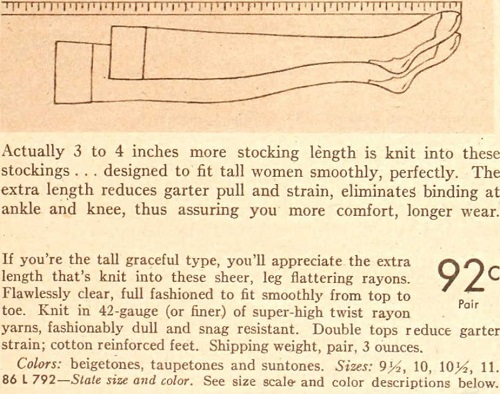

Proportioned Stockings for tall women; Sears, 1958. “The extra length reduces garter pull and strain…”

Finding the right proportioned stocking for your height and weight. Sears chart, 1958. At Sears, your four proportion choices were “petite, shapely, classic, or tall.” (7 sizes x 4 lengths = 28 choices!)

There were so many size variations because 1950s’ stockings did not have much “stretch.” To answer the question “What size?” you needed to know your stocking size and your “pattern” or proportion. (Or you could tell the clerk your height and weight.)

If you wanted long enough stockings, you might have to pay more.

Sears, 1958. The cheaper stockings came in 15 or 30 denier weight, but only one length.

College memory: A friend named Mary was standing in the doorway when my roommate said, “Mary, your stockings are all wrinkled around your ankles.” Mary said, “I’m not wearing stockings. My ankles are sagging.”

Before modern stretch knits, stockings might bag or sag. Worse, if the reinforced top wasn’t high enough, when you knelt down the pull of the suspender could put too much strain on the knee, and your stocking would run or “pop.” Cheap stockings didn’t come in a full range of lengths, so I sometimes came out of church with one or both knees bulging out of big holes in my stockings. All those sizes were necessary because stockings were not very stretchy.

Stocking runs: a tiny hole would unravel the stocking both up and down your leg. This was still true in the 1960s. Lux soap claimed to improve stockings’ elasticity. Ad from 1936.

The stocking clerk might ask, “What weight?” This meant, not your own weight, but the amount of sheerness or strength you needed in the stocking. Light weight 15 denier was very sheer. 30 denier was more durable for everyday wear, and even thicker stockings were available.

“Seams or seamless?” My first stockings had seams, but the seams on the soles of my feet sometimes gave me blisters, so once I discovered seamless stockings, I always bought those. Seamless stockings were available in 1958, but I didn’t discover them for a couple of years. (A vertical seam up the back would have been more flattering to my sturdy legs, but limping on blisters didn’t improve my looks or disposition, so I chose comfort over vanity.) Besides, it’s maddening to be down to your last two intact stockings when you’re dressing for work and find that one of them has a seam and the other doesn’t.

Seamed stockings with reinforced heel and toe (and a seam under the ball of your foot.) Sears, Spring of 1958.

“Reinforced toe and heel? Sandal heel? Sheer foot?” If you wore pumps, then you could buy longer-lasting stockings with reinforced heels and toes. (Toenails or rough heels were hard on stockings.) However, by the 1940s many women wore open-toed or strap-heeled shoes, making the less durable options necessary.

Nude heel or reinforced heel in seamless stockings, Sears, 1958.

“Run stop or regular?” Runs were always a problem. A tiny snag from a chair or a fingernail would start a run racing up and down your leg. Many women kept a bottle of clear nail polish in their purse or desk drawers, because it was the only thing that could stop a run from progressing. If you dabbed a bit on the run before it passed the hem of your skirt, then the stocking might be salvaged enough for future wear. Otherwise, sheer stockings couldn’t be mended. One reason for always buying several identical pairs at the same time: as long as you had two stockings that matched, you could wear them. Once you were down to one stocking, you would probably never find a matching color or knit again, (too many brands, too many choices) so the final stocking might as well be tossed out.

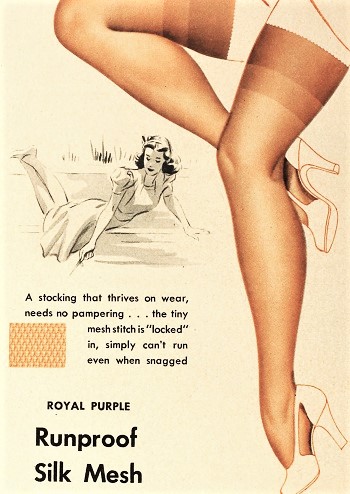

Rayon mesh stockings from Sears, 1944. “Lockstitch resists runs, snags.”

Run-proof stockings were usually a mesh knit. They did get holes, but they didn’t get runs. The holes, however, kept getting bigger….

Mesh stockings did not run, but they did get holes. And the weave was rather coarse and noticeable. Sears’ seamless mesh stockings from 1942.

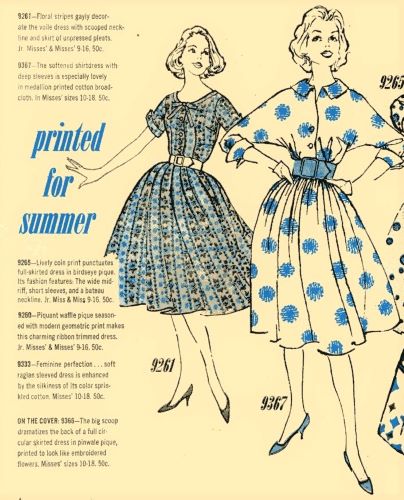

“What color?” Stocking manufacturers and fashion magazines urged women to buy stockings to match every outfit. However, the woman on a budget often stuck to one or two shades. We all had drawers full of not-qute-matching stockings (usually kept in a padded box within the drawer.) Sticking to just one color matching your skin tone (or the healthy tan color you wished your legs were) was the economical choice. However, those black or dark stockings for evening were so temptingly glamourous….

Stockings from Sears to match your skin tone or your dress. 1959 catalog.

If you bought the last pairs of stockings in the box, or the whole box (six pairs,) you would be given the box itself, and therefore you would know the brand and color when you needed to buy more stockings a few weeks later. Otherwise, stockings were simply wrapped in tissue. It was easy to forget where you bought them, the brand, and the name of the color, so your supply of single, unmatched, surviving stockings continued to grow. (One maker’s “nude” or “taupe” was rarely the same as another’s, and “suntan” could mean anything from light golden brown (in expensive brands) to orange (cheaper brands) ….

One Christmas in the Sixties, my father gave me a nightgown set that I didn’t need, so I took it back to Macy’s and exchanged it for a dozen pairs of stockings — two whole boxes! I had several blissful months of not worrying whether I had a pair of stockings that matched. Such luxury!

Next: The Pantyhose Revolution and Supermarket Stockings.

“Fashion is Spinach.” — Elizabeth Hawes.

“Fashion is Spinach.” — Elizabeth Hawes.