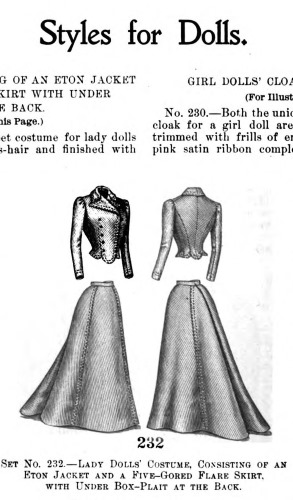

1899 Butterick suit pattern for a “lady doll.” Delineator magazine, November 1899, p 572.

Dolls and doll clothes patterns usually appeared in the November and December issues of magazines like Delineator. I have seen “Fashion Dolls” in museums, but the “Lady Doll” is new to me: an 1890’s version of Barbie — a doll with an adult figure and a wardrobe of current fashions. Butterick patterns made for these dolls were close copies of Butterick patterns for women.

1899 Butterick pattern for a woman’s “tailor” suit. Delineator, December 1899 p 629.

Butterick Patterns for lady doll” clothes from November 1899, Delineator.

Making this in a doll size would be a challenge:

Doll’s suit pattern from Butterick, 1899.

“Dolly” would be wearing a suit very similar to this one for real women:

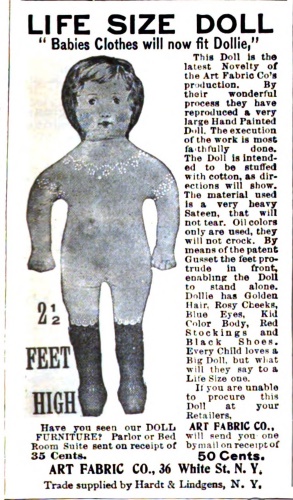

I had a hard time imagining a doll with the tiny waist, large bust, and rounded hips of that year’s corseted figure, but Butterick also sold patterns for the doll herself.

The doll on the left has a very adult figure, with narrow waist and long legs. The porcelain head would be purchased separately. The jointed rag doll on the right has a painted face.

Unlike the “lady dolls,” this 30″ rag doll with painted face was made to wear actual baby clothes.

A very large hand painted doll — but not a “lady doll.”

Lady dolls and fashion dolls, on the other hand, were not intentionally childlike. Like a 20th century doll with a stylized woman’s figure, the whole point of a lady doll was that girls could dress her in grown-up clothing, This fashion doll even wears a corset:

This fashion doll from the Barry Art Museum collection is also described as a lady doll. 17 inches tall, French, circa 1880-1885.

I have always been amazed by the details on Fashion Dolls, and the patterns Butterick sold for lady dolls would require painstaking craftsmanship, especially if the doll was only 16 inches tall!

Lady Doll patterns fit dolls from 16 to 28 inches in height (including head).

This fashion doll is just 17 inches tall. Look at the detail in her ruffles and lace!

French Fashion doll circa 1875, from Barry Art Museum Doll collection.

So I guess it’s not surprising that the clothing patterns for lady dolls assume considerable sewing skills to make such realistic outfits.

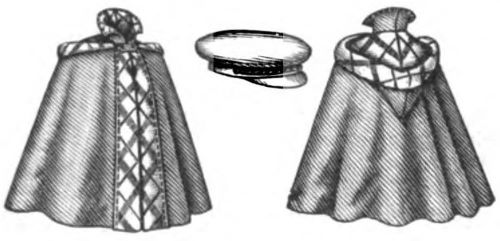

A “Yachting costume” for your lady doll. A yachting cap pattern was included.

Butterick doll pattern for cape, December 1899.

This doll cape pattern is very similar to a Butterick pattern that was available for women:

Woman’s “golf cape” with optional hood, Delineator, November 1899.

A similar cape pattern was available for Misses and girls:

A cape pattern in Misses’ and Girls’ sizes. December 1899, Delineator.

I was delighted to find that a lady doll could also wear a Cycling outfit:

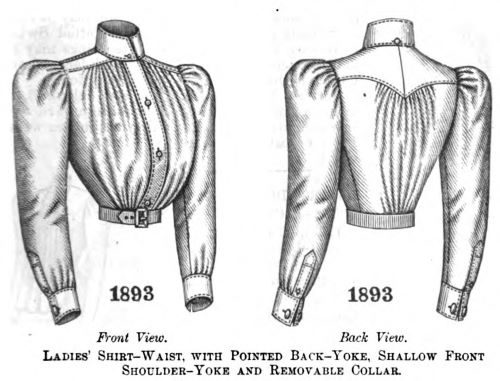

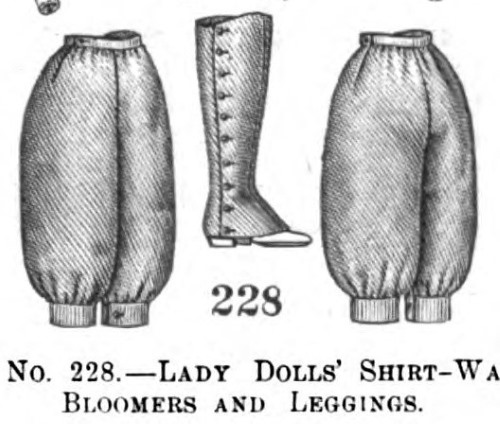

Shirt-waist, Bloomers or Knickerbockers, and gaiters, for a lady doll, resembling the clothes a lady might wear while riding a bicycle.

They are very similar to these real patterns for cyclists:

Butterick pattern 3083 for women’s knickerbockers, Delineator, August 1899.

The knickerbockers would be worn under a cycling skirt. This one is for women:

Woman’s cycling outfit, Butterick 3131 from Delineator, Sept 1899. The skirt is shorter than a normal adult lady’s skirt and has a deep pleat at the back.

Cycling suit for ladies, Sept. 1899.

Because the skirt is shorter than a woman’s walking skirt, buttoned gaiters (here called leggings) prevented legs from being exposed — or splashed with mud.

Gaiters or Leggings covered the rider’s legs to the knee.

Bloomers (or Knickerbockers) and Leggings (or Gaiters.)

Can you imagine finding doll buttons that small, and making those doll-sized buttonholes? The lady doll’s cycling jacket is also rather elaborate:

Lady Dolls’ set no. 227 Consisting of a 3 piece Cycling Skirt, Eton Jacket, and a Tam 0′ Shanter cap. for Dolls 16 to 28 inches. December 1899, Delineator.

Of course, a lady doll’s complete wardrobe would include underwear, a nightgown, a robe, petticoats, etc.

For dolls 14 to 28 inches. Notice her tiny waist and generous bottom!

Lady doll’s nightgown, Delineator, December 1899.

Above, a doll’s robe or wrapper, to be made of flannel.

Lounging-Robe and petticoat, chemise, and drawers for a lady doll.

In 1899, evening and ball gowns often consisted of a separate bodice and skirt. For formal affairs, the neck and arms could be exposed; for dinner parties or formal afternoon events, a separate guimpe was worn under the bodice and provided a high collar and long sleeves.

The combination of bodice (waist) and guimpe would supply 2 different formal looks for a lady (or a lady doll.) Butterick patterns from Delineator, December 1899.

In a series of articles about jobs for women, Delineator interviewed doll dress maker Ernestine Pomroy in December, 1899. She makes it clear that lavish doll wardrobes were a high-priced luxury item for the children of the wealthy. Considering the details on the patterns above, it makes sense that this was a job for the professional seamstress, especially in an era when many women who could afford it also chose their own dress patterns and took them to a professional seamstress to have them made up.

The Interview: “Miss Ernestine Pomroy, looking around for some way whereby she might earn a living, was impressed with the expensiveness of dolls’ cloths [sic] as sold in the New York stores. She made several complete outfits, took them to one of the leading toy merchants and asked for orders. That was her beginning, just a little more than two years ago. To-day she employs four assistants regularly, and in the Autumn, before the holiday season, is forced to employ twelve additional ones for several weeks.When visited in her work-rooms on East Ninth Street the other day, Miss Pomroy, speaking of her work, said: “Of course, I am not the first person who ever made doll clothes for the New York trade, but I believe I am the first person to make it a profession and devote one’s whole time to it. I began just as you have been told, by making a few gowns for children dolls, that is, dolls which are dressed like little girls eight or ten years old. Now, we make them for all ages, though I still prefer to make for dolls of that age.

“While most of my clothes are made to fill orders from the large toy dealers, I have many regular customers among children. They have parents who can afford to humor every whim, and their dolls are brought to me and the season’s outfit ordered, just as its little mistress is taken to the tailor and modiste. In such instances our charges are proportionately large, as no two of the garments are alike, and often the mother of our little customer wishes exclusive designs and will pay for such privileges. This is, as a rule, the case only where the pet is a “lady doll.” Then the costumes of exclusive designs are wished for parties, dinners, weddings or some child’s entertainment. In these outfits we are expected to furnish every article of apparel from their shoes and stockings to their hats. The shoes we buy ready made, or, I should say import, for there is no factory for dolls’ shoes in America; but the hats are made by our milliner and copied after the latest French models.“Doll’s gloves, rubber capes and mackintoshes are made by regular factories in this country, so I have nothing to do with them beyond supplying them to our customers, though in some instances I have designed them for the manufacturers.

“I think there is an opening for such a business as mine in every large city, and I have certainly found it remunerative. It requires, in my judgment, about the same qualities that make a good dressmaker; but I selected it because I found that while one field was over crowded the other was untouched. The result has been highly satisfactory, as my work is both pleasant and profitable.”

If you are interested in dolls, I highly recommend a visit (online, unless you live nearby) to the Barry Art Museum in Norfolk, Virginia. On the campus of Old Dominion University, the Doll and Automata Collection is only one of the museum’s collections. Other departments include Fine Arts and Glass. If you can’t visit in person, visit the Doll Collection online here.

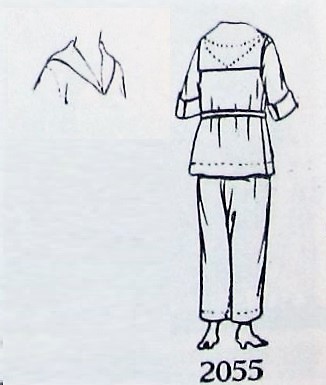

A bit like a masquerade costume is this Asian-influenced pajama set:

A bit like a masquerade costume is this Asian-influenced pajama set:

However, “In war more men die from exposure and illness than from wounds. Every hour that you waste, you are throwing away the life of one of our soldiers.” “Don’t say you are too busy to knit — it isn’t true.”

However, “In war more men die from exposure and illness than from wounds. Every hour that you waste, you are throwing away the life of one of our soldiers.” “Don’t say you are too busy to knit — it isn’t true.”