Butterick pattern 2690, evening gown with camisole top, Delineator, December 1920. This pattern was featured two months in a row.

Evening gowns for misses aged 14 to 19; Butterick patterns from February 1920. Delineator.

The 1920 name for these gowns, bare-shouldered and supported only by straps, was “camisole top.”

Paris fashion by Georgette, illustrated for Delineator in February 1920.

Actresses and couturiers introduced these very bare evening looks before 1920, but I am surprised by how many 1920 examples I found when I started looking — and in just one source, Butterick’s Delineator magazine. [I did find a Standard pattern from 1919 with a straight top, simple straps, and optional sheer, cape-like sleeves at the Commercial Pattern Archive: Standard 391, archive No. 1919.65 BWS]

There aren’t even visible straps holding this bodice up, just the beaded hem of the sheer drape:

Butterick evening waist pattern 2083, Delineator, January 1920.

Digression: Serendipity — here is a surprising discovery I made while reading the text of a 1924 corset ad:

Unfortunately, this corset ad mentioned a strapless brassiere but did not illustrate it. Bien Jolie ad, Delineator, September 1924.

The earliest strapless brassiere I found in the Sears catalog was Fall, 1939.

Only slim strands of beads are supporting this gown from 1920. Delineator, March 1920, p. 128.

The text for this photo concerned the “coils over the ears hairstyle,” and didn’t even mention that very revealing dress. Nor did this photo of a messy “houpette” hairdo have much to say about the beaded straps of this young woman’s gown:

This photo caption did mention “braces over the shoulders,” but was really focused on the “houpette” hairstyle.

“We only meant to show her ‘houpette’ coiffure, but from the braces over her shoulders to the ribbons on her feet she is so utterly engaging that we could find no place to draw the line.”Delineator, March 1920.

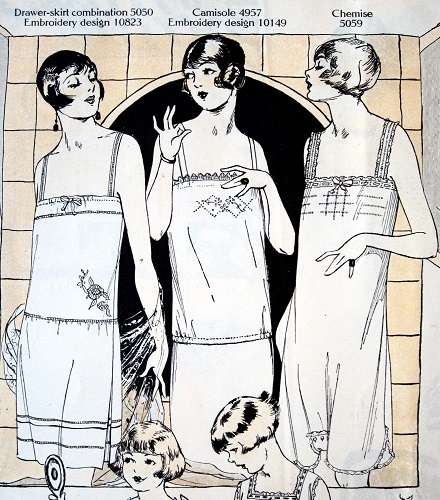

While I recover from that admiring description, perhaps I should mention that the 1920s’ “camisole” was sometimes an undergarment for the top of the body, but also referred to the simple bodice that many 1920s’ skirts hung from.

Later 1920s’ skirts didn’t necessarily hang from the waist; a simple bodice (“camisole”) could be basted to skirts so they hung from the shoulder. Butterick skirt patterns 6601 and 6588, 1926; Warren’s camisole skirt foundation ad, 1924.

One thing “camisole” seems to mean is “a bodice/undergarment suspended from [narrow] straps.” (In 1920, the word “chemise” might also describe an undergarment with narrow straps.)

The narrow straps of these French couture gowns are really minimal: just a strand or two of beads:

Don’t be distracted by her necklace; her dress is ends just above the bust and is suspended from strands of beads. By Drecoll, sketched for Delineator, May 1920.

Evening gown by Beer. Sketched for Delineator, October 1920.

Butterick patterns followed suit:

Butterick 2690, illustrated in November of 1920.

This camisole topped dress came in sizes 32 to 46 bust, and the skirt, embroidered with a spiderweb pattern, seems “vamp”-ish to me.

Butterick embroidery design 10741 is a pattern of spiderwebs.

[Lanvin showed a lacy spiderweb design like this in 1922 (French Vogue, January 1.) ]

The same 1920 issue of Delineator showed a more modest alternate version: sleeveless, with V-neck.

Butterick evening dress 2690, in a more covered-up version; illustrated in Delineator, November 1920.

Yes, this is the same dress as the black, very bare version at the top of this post; that illustration was from December 1920.

Butterick 2690 with the camisole top and the “pleated panels” skirt. December 1920. It seems to be black, but might be any dark color.

Delineator showed women how to make “Paris” trims for evening dresses:

“Making Paris Trims” article from Delineator, March 1920, p. 147. [Several of the dresses for misses have this high waist and a strap top.]

These very bare dresses for misses have beaded straps:

Butterick 2067 for young women aged 14 to 19, February 1920.

Butterick dress 2702-B is a camisole top dress. For misses 16 to 20. Delineator, November 1920, p. 127.

Butterick 2702-B next to a V-necked dress more usual in the evening wear of the mid-1920s. Actually, they’re the same pattern…!

The “conservative” dress pattern (2702-A) also included a camisole top version (B); what’s more, No. 2702 is the “size 16 to 20 years” version of Butterick 2690! Butterick was really committed to these styles.

Butterick 2702 is a teens’ 16 to 20 version of 2690, illustrated in two camisole versions and a pale blue sleeveless one earlier in this post! 2702-A is like the sleeveless version of 2690, but with an optional sheer sleeve.

Straps didn’t have to be beaded:

Butterick 2181; February 1920. Two different straps.

Party looks for “debs and sub-debs,” Delineator, Feb. 1920.

The contrast between the covered-up and very bare dress is striking, and reminds me that young men returning from war were more accustomed to the #2151 kind of party dress (above left) than the “nothing under this dress but me!” #2181 (center.)

Two dresses with strap tops, and a slightly more conservative one, right. #2130 is actually pretty revealing, too, since it has a very sheer layer over a camisole top.

The sheer-over-camisole-top versions were probably chosen by girls (or their mothers) who were not ready to show off so much bare skin. All these alternate views include a sheer sleeve.

Paris designer Elise Poret showed a sheer layer over her bare, camisole-strapped bodice in February 1920.

Party dresses for 14 to 19 year-old women. Butterick 2107 and 2238, March 1920.

The dress at left has a gathered sheer layer over a camisole top. Most 1920 evening dresses were not bare, camisole topped fashions. This pattern is another from February 1920.

Butterick evening waist pattern 2172 with skirt 2166. February 1920. The horizontal line of the camisole layer is partially covered by the V-shaped top layer.

This dress, Butterick 2682, does not have the dropped waist of the later nineteen-twenties, but the V-neck and sleeveless bodice are very typical of those years.

However, the popularity of camisole-topped dresses — bare, revealing dresses — is shown by their appearance in these ads:

Ad for Woodbury soap, for “the skin you love to touch.” Delineator, March 1920.

From an ad for Cuticura soap, November 1920.

From an ad for Cutex nail polish. September, 1920. Two different straps.

From an ad for DeMiracle hair remover, “every woman’s depilatory.” Delineator, January 1920.

Detail, cover of Delineator Magazine, October 1920.

The initial shock of dancing with young women in scanty, revealing clothing didn’t happen in the “Roaring Twenties.” It began with the “lost generation” right after World War I. ” …Members of The Lost Generation had survived World War I but had lost their brothers, their youth, and their idealism.” They didn’t “discover” sex, but they certainly discussed it more frankly than their grandparents had.

A bit like a masquerade costume is this Asian-influenced pajama set:

A bit like a masquerade costume is this Asian-influenced pajama set: