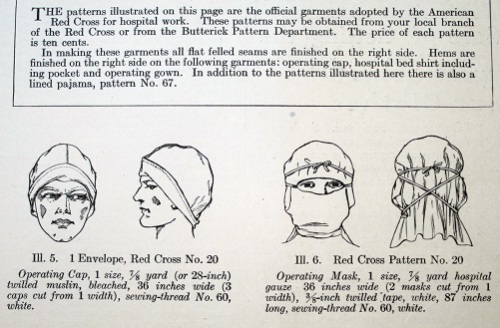

The appalling carnage of World War I is often given in statistics; these Red Cross patterns and instructions for volunteers — making hospital gowns, bandages and wound dressings, surgical masks and gowns, etc. — also remind us (and those Red Cross volunteers) of the suffering it caused.

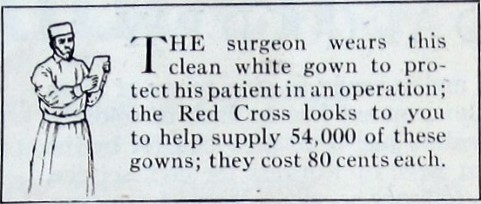

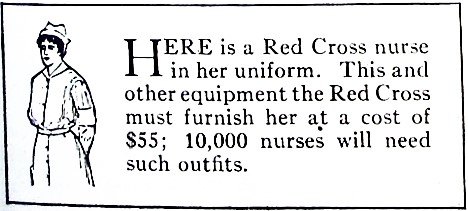

Women’s magazines like Delineator and Ladies’ Home Journal published government information as well as encouraging volunteer work. The patterns above are for operating room personnel.

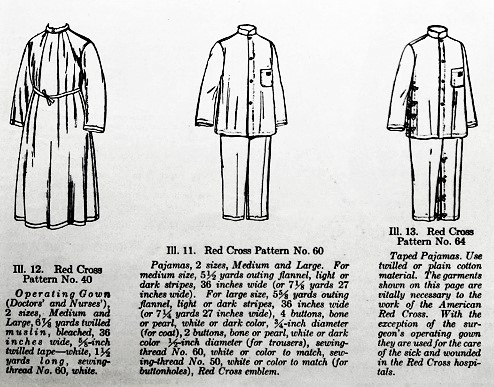

A surgical gown for doctors and two kinds of pajamas for hospital patients. Delineator, Nov. 1917.Red Cross patterns were available for sewing groups or individual volunteer stitchers.

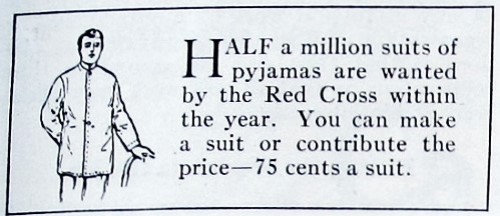

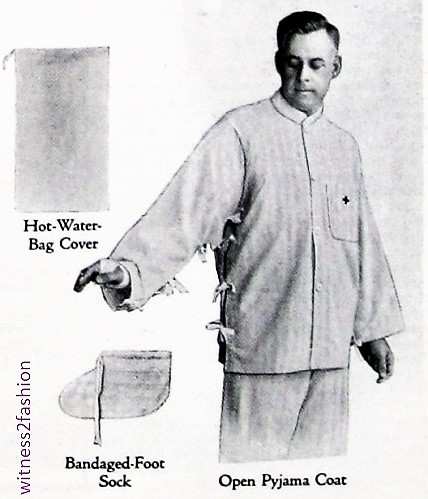

Operating room gear — like surgical gowns and sterile shoe covers — could be made using regulation Red Cross patterns. Pajamas for patients were also in demand. The “taped” pajama below opens so the injured soldier need not be moved for his wounds to be inspected and dressed.

Red Cross regulation “taped pajamas” for the wounded and socks for injured feet; Ladies Home Journal, Dec. 1917.

Making these garments must have reminded civilians that soldiers were receiving terrible injuries.

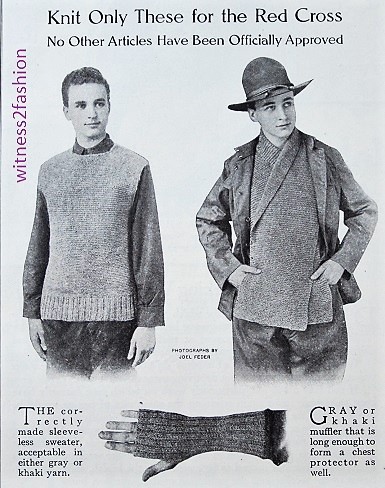

Women and children were encouraged to knit Red Cross regulation sweaters, socks, and even “helmets” that kept heads and faces warm.

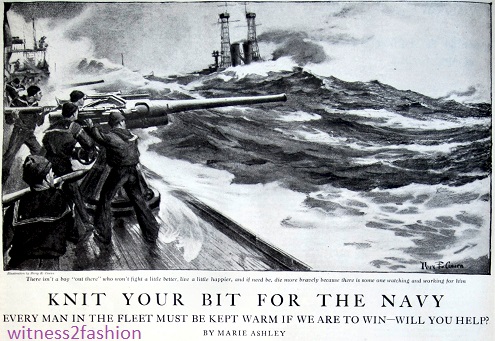

“Knit Your Bit for the Navy” article, Delineator, August 1917. “Every man in the fleet must be kept warm if we are to win — will you help?”

Delineator, November 1917.

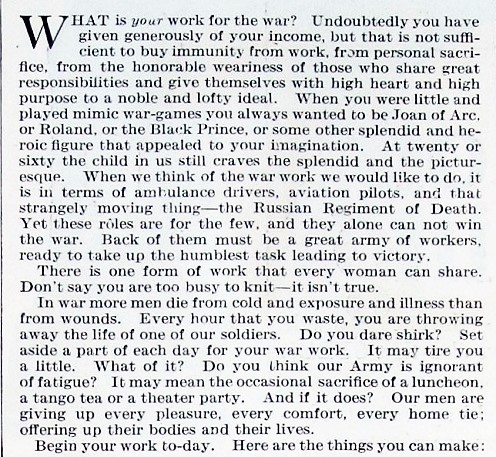

Red Cross volunteers also made:

Not just knitting: List from Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1917. The same information ran in several women’s magazines, but each magazine formatted it differently.

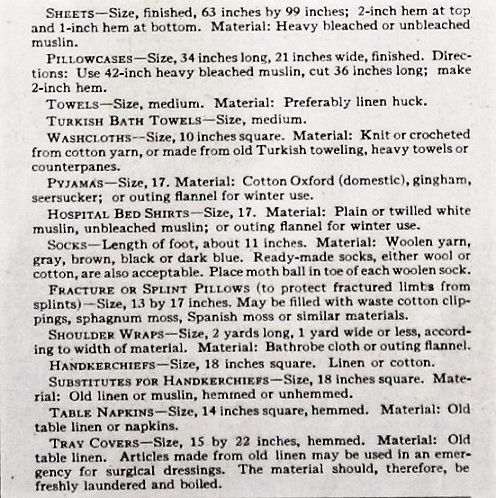

Many women imagined themselves doing “glamorous” war work, like nursing or ambulance driving. (They had no idea of the horror those women faced daily.)

However, “In war more men die from exposure and illness than from wounds. Every hour that you waste, you are throwing away the life of one of our soldiers.” “Don’t say you are too busy to knit — it isn’t true.”

However, “In war more men die from exposure and illness than from wounds. Every hour that you waste, you are throwing away the life of one of our soldiers.” “Don’t say you are too busy to knit — it isn’t true.”

Items to Knit for the Red Cross, LHJ, October 1917.

Initially, there was such an outpouring of knit garments — many totally unsuitable for the Front — that the Red Cross used women’s magazines to explain why regulation colors and instructions had to be imposed.

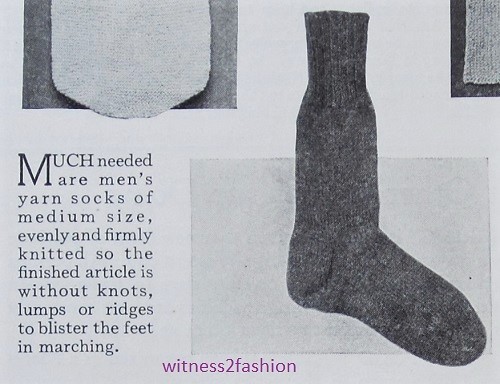

A poorly knitted or fitted sock could have a serious impact on a soldier. Blisters and foot infections sent many to the hospital. LHJ, Oct. 1917.

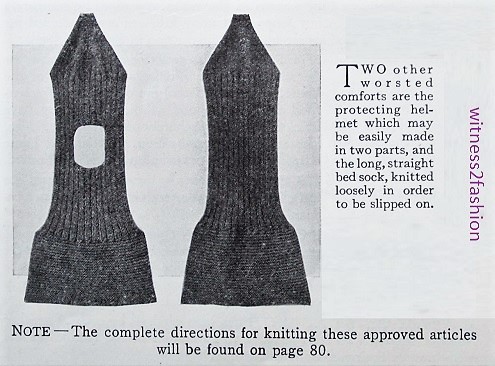

The front and back of a knitted “helmet.” LHJ, Oct. 1917.

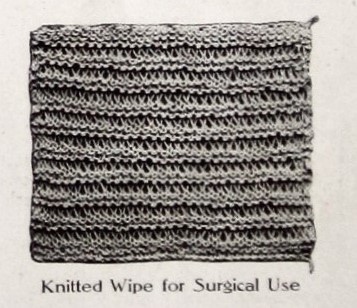

More disturbing knitting supplied the operating room:

Knitted Wipe for Surgical Use, LHJ, July 1917.

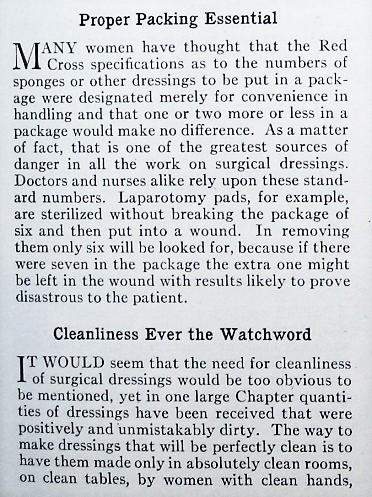

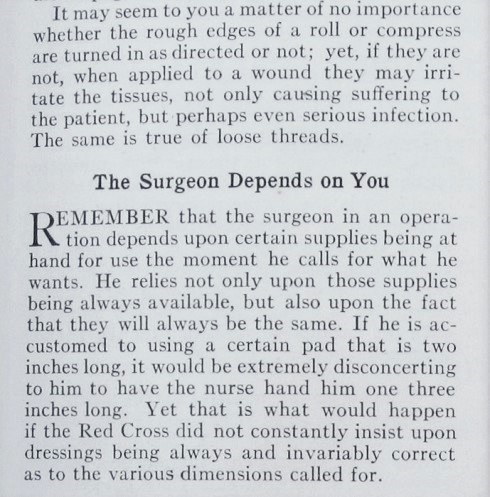

Some volunteers chafed at the Red Cross rules, so regulations had to be explained and justified — repeatedly.

LHJ, October 1917. (Laparotomy is an abdominal surgery procedure.) Sterile dressings needed to be made in supervised rooms, not at home.

LHJ, October 1917. Even a loose thread could cause infection.

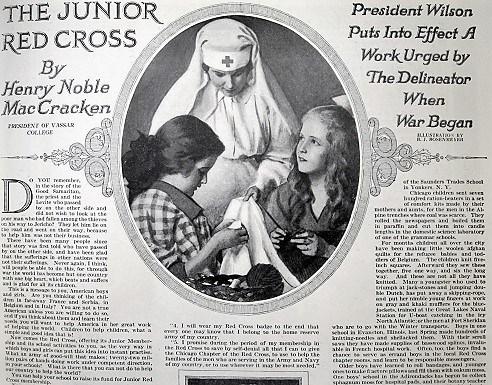

Children were also encouraged to knit for soldiers and sailors:

Article recruiting members of the Junior Red Cross, Delineator, November 1917. Even beginning knitters could manage to make mufflers and wristlets.

Junior Red Cross war work suggestions. Delineator, Dec. 1917. “Uncle Sam needs a million sweaters NOW. There are twenty-two million of you [children.] If you work, every soldier under the Stars and Stripes will have his sweater.”

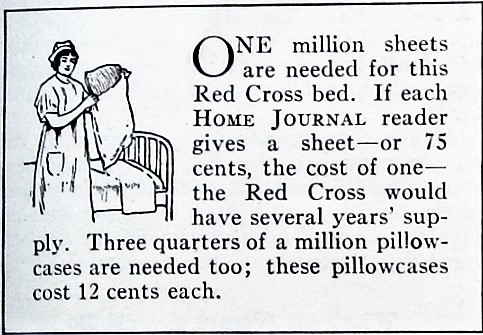

LHJ, August 1917.

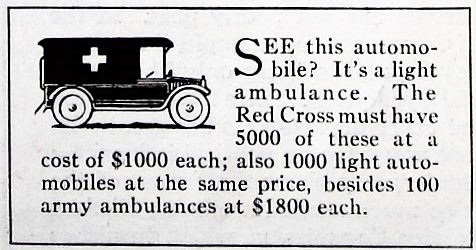

LHJ, October 1917. All these “boxed” images are from the same article.

The Armistice treaty which concluded “the War to End All Wars” came into force at 11 a.m. Paris time on 11 November 1918 (“the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.”) — Wikipedia.

About 8,500,000 soldiers had died. Over 21 million were wounded.