After the U.S. declared war in April of 1917, there was a great outpouring of volunteerism. Women were eager to support “our boys,” and magazines aimed at female readers were a perfect, pre-existing medium for the government to communicate with millions of households all over the country. Official articles like the ones quoted here appeared in both Butterick’s Delineator and Ladies’ Home Journal, among others.

Women Wanted to Wear Uniforms, Too

So many women wanted to wear some type of official uniform while doing “war work” that cautions were repeatedly issued.

Official Red Cross policy statement by William Taft, Chair of Central Committee, August 1917 issue of Ladies Home Journal.

The new, authorized Red Cross Corps uniforms (pictured above) were described in September, but the problem of unauthorized used arose again in October:

Clearly, there were unscrupulous people “raising money for the Red Cross” but not turning over all the proceeds to the charity. “Red Cross Bazaars” had to have prior approval at the local level or use of the name was not permitted. And only members of the Red Cross who had taken a loyalty oath and met other requirements could wear Red Cross uniforms.

There was a difference between being a Corps Member and being a Red Cross Nurse — only women who had completed two years of nursing training, who had an additional two years practical nursing experience, and who were registered nurses in their own state could apply to be a Red Cross Nurse. However, there were many other vital ways for a woman to serve through the Red Cross. Wearing any of these Corps uniforms required a permit.

American Red Cross Supply Corps Uniform & Clerical Corps Uniform, 1917

Supply Corps Uniform

“In this division of Red Cross Work the service of the members is to prepare surgical dressings, hospital garments and all other Red Cross supplies. The uniform is a white dress, or a white waist [i.e., blouse] and skirt, with dark blue veil and white shoes. Small Red Cross emblems are worn on the veil and on the left front of the dress. The arm band is dark blue, with a horn of plenty embroidered in white.” [Her scalloped collar gives the impression that she is wearing white clothing she already owned with the uniform head covering and armband.]

Women who wondered why they had to wear a head covering while making bandages and dressings were reminded that this was necessary “for sanitary reasons;” “she must also wear an apron for the same purpose.”

The Demand for Bandages: “The Red Cross could send all its available supply to Europe for instant use there and start all over again. . . .Wounded soldiers in France to-day are being bandaged with straw and old newspapers.” — William Howard Taft in Ladies’ Home Journal, August, 1917.

The official Red Cross patterns for making pajamas, surgeon’s gowns, etc., were available from pattern companies, stores, or Red Cross Chapters for 10 cents each.

Clerical Corps Uniform

“This service is designed to include the women who do the large amount of clerical work in an active Red Cross Chapter — the volunteer stenographers, bookkeepers, etc. The uniform consists of a one-piece gray chambray dress, a white, broad collar, white duck hat with yellow band, and white shoes. The Red Cross emblem is worn on the hat and on the left front of the dress, while the arm band is yellow, with two crossed quill pens embroidered in white.”

By October, the national headquarters of the American Red Cross was receiving 15,000 letters per day. To cope, it was decentralized, with thirteen divisions spread to large cities throughout the U.S. When you consider that women all over the country were being asked to roll bandages, to make hospital garments and supplies such as sheets and pillowcases, to knit warm scarves, sweaters and socks for servicemen, and to supply 200,000,000 “comfort kits” for soldiers, you can imagine the logistical nightmare of shipping and sorting that had to be done by the Supply Corps and the Clerical Corps. Shipping companies agreed to deliver packages addressed to the thirteen Red Cross collecting centers for two thirds the usual price, but all shipments from local Red Cross chapters had to have separate notices of shipment mailed, as well.

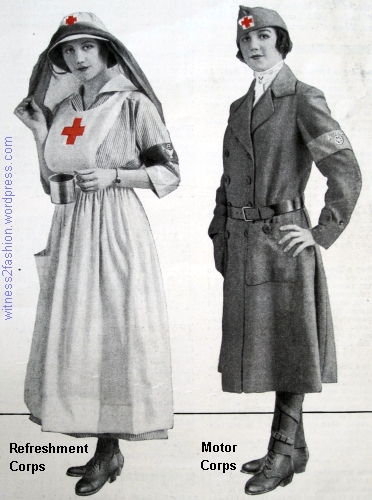

American Red Cross Refreshment Corps and Motor Corps Uniforms, 1917

Refreshment Corps Uniform

“The Corps feeds soldiers passing in troop movement or en route to a hospital, or furnishes lunches in the way of extras to troops in near-by camps. The uniform is a dark blue and white striped chambray dress, long white apron with bib, white duck helmet with dark blue veiling, and tan shoes. The arm band is dark blue, with a cup embroidered in white. A large Red Cross emblem is worn on the apron bib and a small one on the helmet.”

Presumably because of the dangers of fraternization, “no person under 23 years of age may be a member of the Refreshment Corps.” Also, because attempts had been made “to injure our soldiers through tampering with Red Cross articles,” all foodstuffs had to be prepared in supervised kitchens and “by persons whose devotion to the United States can be vouched for.” (Taft, October 1917.)

Motor Corps Uniform

“All women volunteer drivers for Chapter work are included in this service. Members may or may not furnish their own cars. The uniform is a long gray cloth coat with a tan leather belt, a close-fitting hat of the same material, riding breeches, tan puttees or canvas leggings and tan shoes. The Red Cross emblem is worn on the hat. The arm band is light green embroidered in white.”

Although her riding breeches are modestly covered by the length of the coat, this is a variation on a male chauffeur’s uniform. Most cars were open (and cold) in 1917. Whether or not you supplied your own vehicle for transporting troops, this uniform had to be purchased, not home-made. It cost about $25.

Who Can Wear These Red Cross Uniforms?

American Red Cross Nurses Uniforms

Alessandra Kelley, who writes the blog Confessions of a Postmodern Pre-Raphaelite, found a 1918 copy of The Red Cross Magazine with pictures and descriptions of the official uniforms for Red Cross nurses at home and serving overseas. She kindly photographed it in detail for the use of historians and re-enactors. Click here for a link to her great post about Nurses Uniforms.

I have also written about the U.S. Food Administration Uniform, 1917.

Well, it’s hard for me to imagine this fascination for uniforms. I can see why people working in the field would want to be seen as part of a group, but office workers? But I love your documentation, and especially the wonderful red of all those red crosses.

Pingback: “Original and Becoming” Work Clothes, 1917 | witness2fashion

Pingback: Butterick Fashions for August, 1917 | witness2fashion

Pingback: Red Cross Motor Corps, Washington D.C., 1917 | Colorem

Pingback: “Service Suits” for Girls, Boys, and Women in 1917 | witness2fashion

I’m sure it had to do with this great national feeling of unity that developed in the country to support, be like as much as possible, be “one” with “our boys,” and to wear a special, distinct uniform of any kind that would put their patriotic fervor on display to as many others as possible.

It was likely the female version of “I’m joining up TODAY, to go right ‘over there’ as soon as possible to fight the Hun, beat the Kaiser, and win the Great War!!” Men who didn’t qualify for military service, and who had to stay home in civilian clothes were frequently looked down upon on sight alone, no matter what they really did, and were harassed and sometimes even pushed around, by the men who WERE in uniform. NOT condoning any of it, mind you, but still, it did happen.

The women who were just itching to serve in any way possible, frequently joined the most visible and publically respected organization of the time, The American Red Cross, which was an official, all-uniformed organization. To allow one or two groups to have special uniforms, and be highly visible to the public, and the not others, would have cut a wide swath through the morale of that great group, who were anxious to do their own bit, whether it involved making surgical bandages, hospital “pyjamas” [sic], doctors surgical gowns, sheets and pillow cases, etc., or pouring coffee and delivering doughnuts to hungry troops passing through town, or handling the seemingly unending stream of “official” Red Cross paperwork and documentation that was required to send anything anywhere.

Some portions of those uniforms were actually functional, as well. For instance, the hair covering veils worn by the women who made Surgical dressings, kept their hair from becoming trapped within the folds and layers of those dressings. Cleanliness was paramount in an age which did not include antibiotics!

And, to differentiate between the nurses and the other groups of non-nursing staff was important, for the benefit of the public, and other Red Cross staff themselves. Knowing who did what, simply by observing their uniforms was quite helpful when seeking out someone to do a specific task. Wearing street clothes would tend to make the staff who wore them seem somehow less important.

Yes, it would be important to recognize which Red Cross workers were clerical and which were medical personnel. But it’s also obvious from the many warnings that some women wanted to “look the part” without actually being qualified or prepared do do the work. But there was an outpouring of volunteers — American women had been reading about the war for years, before the U.S. was officially at war.

Yes, WWI, which never had anything to do initially with us, and which was begun over something which should never have triggered such a bloody conflict to begin with, had been going on since 1914, and it took three whole years to include us in the “guest list.” So, plenty of publicity and propaganda was already embedded in the American press before we ever got busy “over there.”

And, I think the bit about some of the women who had to be repeatedly warned about not looking the part if they weren’t prepared to play the part, isn’t all that terribly surprising for the times. Up to that point, few if any women really had any official role to play in any real way, in which they would be specially recognizable outside of the rest of the general population.

Nursing, and it’s recognizable, specially designed uniforms and caps, had only been officially established and recognized in the very last portion of the 1800’s, and so had very little time in the American consciousness, and only involved single women, as married women were not accepted for training in the schools that existed at the time. It took WWI to really put the active, publically participating woman in the forefront of the American home front at that time. Especially munitions plant workers and other jobs that had been exclusively men’s jobs prior to the Great War.

A fairly large book has been researched over a period of several years, written and recently published about a very large community which sprang up almost overnight near Williamsburg, Virginia, called Penniman, during the last part of the war years, which gathered together almost all the employees of a DuPont owned munitions plant, to house, feed, employ and care for its employees, a high percentage of which were women, and then within less than five years, had disappeared all together. No houses, other buildings, the plant itself – nothing is left there to mark its previous existence.

Many of the houses weren’t torn down – they were sold to business owners involved in real estate in different ways, and lifted up, and moved to other locations! Some even were transported on barges down the Elizabeth River, where many have been discovered, still extant, and identified in Portsmouth and Norfolk, and a few buildings including some of the houses, had been moved to nearby College of William and Mary (as known then), and Williamsburg proper, and reused for many years. It’s quite a book, and contains a great deal of information which took years to track down. The contribution of the women there, many of whom put their own lives at stake, not only working in a highly explosive environment, but also through sustained contact with some very deadly chemicals in the process, wasn’t something to be brushed aside as insignificant.

Thank you for this interesting information about Penniman! If you can find a copy of Ladies’ Home Journal for November 1917, there is a long article about women working in factories to produce ammunition, uniforms, etc. It’s “What Are These War Jobs for Women?” by Dudley Harmon, LHJ, Nov. 1917, page 39 and many other pages. (Page 92, “Where the War Jobs Are,” lists hundreds of jobs for women on a state by state basis. But Penniman wasn’t yet listed in Virginia.) Also in November 1917, Delineator ran a long article (beginning on p.50) in a series of “Women’s Preparedness” columns — it was called “What Can I Do to Help?” and offered a variety of suggestions and places to send inquiries. I’m not sure researchers have always realized how much can be found in so-called “women’s magazines.”

Thanks for that! Penniman wasn’t a latecomer to our War Effort of the time, because they were already in operation by summer of 1916, making dynamite for E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company of Wilmington, Delaware on 6,000 acres of choice Virginia farmland, but DuPont (as later known) spent over $11 million to create a “world-class” munitions plant when we entered the fracas on April 6, 1917. They eventually had just four shell loading plants in the country, and only two government financed shell loading plants in the summer of 1918, Penniman being one of the two. They of course picked their locations based on shipping convenience. The convergences of the York River and the Chesapeake Bay provided that location. For most of the War, the Great Atlantic Fleet of the Navy was anchored at their very front door.

Their shells didn’t contain shrapnel, but high explosives, TNT and Amatol, and were designed to take out trenches, fortifications and inanimate objects. The TNT was heated in massive hot kettles, heated to 105°C and then poured into the empty shell casings. By the end of the War, 2.8 million shells had been produced at Penniman. They made 75mm and 155mm shells, both bullet shaped casings, the smaller weighing around 15 pounds, and the larger over 100 pounds!

In October of 1918, just barely before War’s end, an enormous explosion occurred at the other Government financed shell loading plants in northern New Jersey, killing over 100 people, and it took three DAYS for all the explosives to blow themselves up, raining down explosive debris within a two-mile radius of the plant!

The women, which you might be most interested in, comprised 90% of the “operatives” on the shell loading lines at Penniman. Nationwide, about 50% of all the munitions workers of all companies were female. Here’s a bit of information you will NOT find in your ladies magazines, or likely anywhere else, except the Lancet, the UK’s Medical Journal, or much more contemporary sources produced since then. The women who worked these lines had eventually been nicknamed “Canaries,” and here’s why. The women, who worked with the powdered TNT, even though it was so toxic that it caused not only sneezing, coughing, sore throat, sinus pain and watery eyes just on initial exposure, but after one 8 hour shift, many women experienced “colic” (diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.) After a couple of weeks, their skin and hair turned “a dirty, awful yellow,” and their lips were a lilac blue, because the TNT damaged the bone marrow’s ability to produce red blood cells, which carry oxygen!! It also depressed production of white blood cells, and otherwise compromised immunity. In some plants, their appearance was so alarming, they were segregated at mealtime. [The Spanish Influenza epidemic ran rampant through Penniman in October, 1918, with a mortality rate so high it was considered barely credible at the time. The morticians ran out of caskets, and bodies were stacked in trucks waiting for burial. All the while, in nearby Williamsburg, no deaths were reported from the flu at all.]

The Lancet did an in-depth story on the problem, but it was completely hidden from publication in the main stream media, because of (the quite obvious) belief that if the real truth got out, it would decimate the employment rolls already existing, and thoroughly discourage potential ones! (Do ya THINK?? HIDE the truth – it will scare the daylights out of the women who want to work here and do this dirty, toxic, deadly job!)

Penniman, as it turns out, had existed in and disappeared from, my back yard growing up! And that was right on the shipping and harbor location in the biggest natural harbor in the world, on the Chesapeake Bay. Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock ports, both for private and for the United States Navy, have been located there since the late 1880’s, and that location in Newport News, VA was a major embarkation and return point for the East Coast during both big wars, as well as a major shipping producer for them both as well. “Hilton Village”, a historically marked and still preserved and occupied housing development on the edge of the old City boundaries, was one of the very first government planned and established “planned developments” during the latter portion of WWI, and is still beautifully preserved and occupied today! It’s quite a desirable area for their homes, and historic prominence. Many photographs of it’s original building are available on their own website.

There is a small version of the Arch de Triómphe (?? Well, “Arch of Triumph”, in my much better English!) very nearby the point where the soldiers and sailors would leave their ships there, and they would traditionally march right under and through it (it’s smaller than the original, but it’s not a tabletop size!) on their way to their parades of valor through the streets! I lived in this area for the first 20 years of my life, and consider myself still a native Virginian, even though I have lived in Indiana for the last 40 years since then!

(I always attribute my sources, when information has come from other sources, therefore – All descriptive and sociological data given here regarding Penniman, comes strictly through my reading of the book, “Penniman – Virginia’s Own Ghost City” Rosemary Thornton ©2016; Gentle Beam Publications, Portsmouth Virginia.)

It’s good that the sacrifice of these patriotic women is finally being made public. There is a lot about WW I that was not known by the public until much later; truth was suppressed to protect morale. We who were born later have seen the film footage and still photographs of the trenches, but the public, at the time, did not. In fact, the stage production of Oh! What a Lovely War in 1963 was an extraordinary history lesson for most of us, in the form of a musical review using real songs from the war. The movie based on the musical had the songs, but not the impact.

Well, here I am, two years later. I stumbled back across this post just now, from a Pinterest post. Reread everything, and tried using the links to “Alessandra Kelley, who writes the blog Confessions of a Postmodern Pre-Raphaelite,” and the link to her article about nurses uniforms, 👩🏻⚕️, only to find that neither of them function any longer. I am sad now, as I was really looking forward to rereading them! 🙇🏼♀️ It’s a shame that such things just disappear from sight!🤷🏼♀️

Ah well, maybe I can dig it up on the archive.org “Waybackmachine”! 🙋🏼♀️

Sorry about that! A genealogy book suggested that, when a link doesn’t work, trying shorter and shorter bits of it sometimes gets you to the original source — like cutting off a segment of the “tail” till you’re down to the basic site address. I haven’t tried to follow up this way — just a thought.