Andre Studio Collection: Reefer Coat design by Pearl Levy Alexander, 1939. Image Copyright New York Public Library.

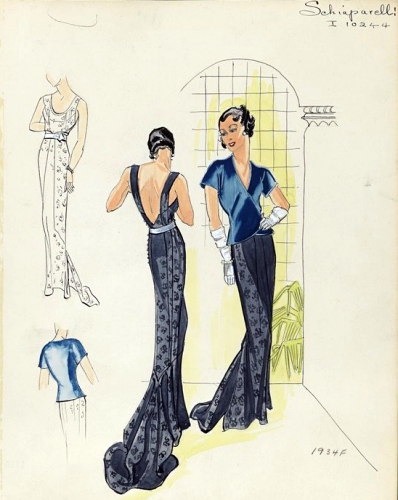

Andre Studios in New York was a business which produced sketches of French couture, with variations for the American market, selling the sketches to clothing manufacturers from about 1930 on. A collection of 1,246 Andre Studios sketches from the 1930’s is now available online from New York Public Library and from the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA.) The name on most of the sketches is Pearl Levy Alexander, and that is the best online search term.

NOTE: please do not copy or republish these images; their copyright belongs to the New York Public Library and they have been made low resolution as required by NYPL.

An excellent article about the Andre collection can be found here as a pdf. (The name of the article’s author is missing!) It explains how (usually unauthorized) sketches of couture wound up in the hands of dress manufacturers, to be copied or modified as they worked their way down the economic scale, eventually reaching the cheapest parts of the mass market.

In fact, Pearl Levy Alexander signed/designed many hundreds of sketches which included Andre Studios’ suggested modifications and variations of current designs.

The designs in the Andre Collection may include adaptations suitable to the American market, but some have attributions to known couturiers — e.g., “Import R” was their code for Patou — as on this red wool siren suit (for wearing in air raid shelters) designed by Jean Patou in 1939.

Andre Studios’ sketch of a red wool “siren suit” by Patou. 1939. “R” was the import code used for Patou. Image Copyright New York Public Library.

You can recognize Andre’s “Import Sketches” of original couture because they were done in black and white; the modified designs, suitable for U.S. manufacture, are more elaborate drawings and use some gouache — white or colored watercolor. This “black marocain” suit is an actual sketch of a Chanel model; in the lower right corner you can see “Spring/Summer 1938; Import Code J = Chanel.”

This sketch says “Designed by Pearl Alexander” but acknowledges that it is “after Molyneux” — not an exact copy.

“Boxy coat after Molyneux” 1940, designed by Pearl Alexander, is Alexander’s modification of a Molyneux design. Image Copyright NYPL, Andre Collection.

On the other hand, this suit, dated 1/30/39, simply says it is designed by Pearl Levy Alexander. The sketch is highlighted with white opaque watercolor (gouache) and has a pink hat and blouse.

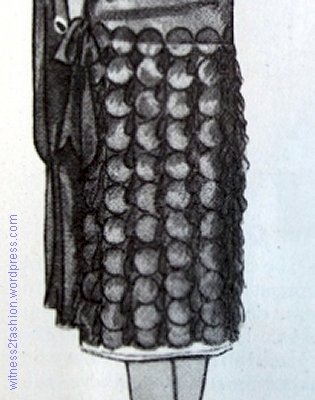

This black and white sketch is a 1938 suit by Schiaparelli (Import Code AO):

Andre Studios’ sketch of an original Schiaparelli suit, with a note about the embroidery. (1938) Copyright New York Public Library.

If you are looking for designs by particular couturiers, look at the last two images in the collection. They are lists of designers’ names; the “Import Key” for Spring/Summer 1938 is a long list of designers whose work was sketched for Andre’s manufacturing customers, including Chanel, Heim, Lanvin, Vionnet, Nina Ricci, Redfern, Mainbocher, Patou, Paquin, Schiaparelli, Worth, and many less remembered designers, like Goupy, Philippe et Gaston, Bernard, Jenny, et al. You can see it by clicking here. A search for these individual names may (but may not) lead to a sketch. (There’s also an Import Key for 1939-40.)

World War II momentarily cut off free access to Parisian designs, and this particular NYPL collection of sketches ends in 1939-40. However, Andre Studios continued to produce sketches into the 1970’s.

Three Sources for Andre Studios Research

In addition to the portion of the Andre Studios collection donated to New York Public Library — over 1,200 sketches made available online — the Fashion Institute of Technology (NY) and the Parsons School of Design also received parts of the collection of Andre Studios’ sketches and scrapbooks, photos, news clippings, etc., which were donated by Walter Teitelbaum to (and divided among) all three institutions.

The Parsons School has information about its Andre Studios collection here, including this sketch of four coats designed by Dior in 1953. Parson also supplies information about other places with Andre Studios and Pearl Alexander archives.

FIT has not digitized its part of the collection, but researchers can visit it. For information, click here.

Bonus: More Thirties Designs in the NYPL Mid-Manhattan Collection Online

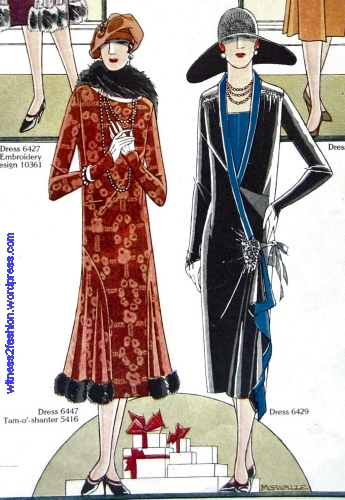

Image from New York Public Library’s Mid-Manhattan Collection. Copyright NYPL. “Dormoy’s Frock, Agnes hat, Chanel, Molyneux, Mainbocher.”

Another, completely different collection of fashion sketches from the 1930’s — many in full color — can be found here, at the NYPL digital collection, in the Mid-Manhattan Collection. [Note, when I asked it to sort “Costumes 1930s” by “date created,” images from 1937 came before images from 1935, so don’t assume it’s chronological.]

Nevertheless, if you explore the alphabetical list at the left of the Mid-Manhattan Collections page, scroll down, down down under Costume, and you’ll find many images by decade, before and after the nineteen thirties! I was surprised by this 1850’s bathing costume cartoon:

![1916 designs by Gabrielle Channel [sic] from Doris Langley Moore’s Fashion through Fashion Plates, cited by Quentin Bell.](https://witness2fashion.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/chanel-1916-bell-plate-39-from-fashion-through-fashion-plates-doris-langley-moore.jpg?w=500)