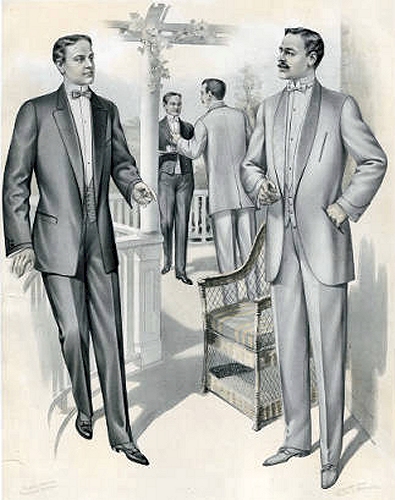

How did men go from wearing suits like this:

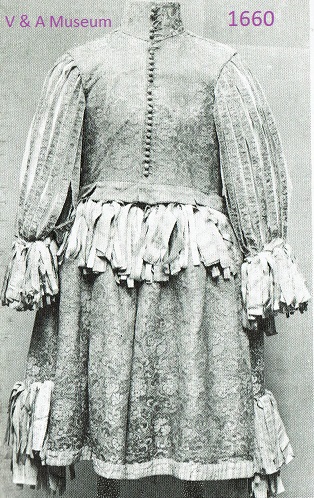

Petticoat breeches, British, 1660. Victoria and Albert Museum; image from Boucher, 20,000 Years of Fashion.

… to wearing suits like this?

Man’s three piece suit illustrated in Esquire, Autumn, 1933.

Suit with petticoat breeches, from Boucher; 1666. You couldn’t have too many ribbons….

There aren’t many changes in fashion which can be dated to a specific moment, but the change from petticoat breeches to the trio of coat/jacket, matching breeches, and a matching or coordinating vest was inaugurated in England on Monday, October 15, 1666. It is considered to be the birth of the Three Piece Suit.

When Charles II was restored to the throne of England after years of Puritanical rule, the king brought with him the extravagant styles worn in European courts.

English King Charles II with his queen, 1662. Source: Cunnington: Costume in Pictures.

In October, 1666, Charles declared his intention to start a new fashion for men. Diarist Samuel Pepys held an official position in government and was present at the court of King Charles II on that day. When Pepys went home, he wrote in his diary for October 8:

“The King hath yesterday in Council declared his resolution of setting a fashion for clothes, which he will never alter. It will be a vest, I know not well how; but it is to teach the nobility thrift, and will do good.”

NOTE: About the word “vest:” The gulf between British and American English may be more confusing than usual, because clothing vocabulary is very subject to change. (For example, a “bodice,” i.e., the top section of a dress, began as “a pair of bodies,” meaning the two sides of a corset.) In 20th c. England, “vest” came to mean a sleeveless undergarment worn by men, while they called the garment which goes over the shirt but under the coat a “weskit” or “waistcoat.” However, in 1666, even in England, although the vest was worn under a coat, a “vest” was meant to be seen, and through the 18th century, a vest might even have sleeves. Perhaps we should think of Charles II’s “Persian vest” as a “vestment” or “clothing” rather than the waist-length garment the “vest” later became, especially in America.

After a few years in England (and perhaps in a spirit of competition) Charles decided to break with the distinctly un-thrifty French fashions of Louis XIV’s court. (One way Louis kept his nobles from becoming too powerful was by forcing them to live at court and spend lavishly….) Here is King Louis in his petticoat breeches and cropped top:

King Louis XIV receiving Swiss Ambassadors, 1663 painting by Van Meulen. From Boucher’s 20,000 Years of Fashion.

Why a “Persian vest?” The English writer (and courtier) John Evelyn had returned from travels in the East in 1666, filled with enthusiasm for the men’s clothing he saw there. (See Barton’s Historic Costume for the Stage.)

Once King Charles II had declared his intention of starting a new fashion for men, his courtiers literally tried to “follow suit.” On Saturday, October 13, Pepys visited the Duke of York, who had just returned from hunting and was changing his clothes. “So I stood and saw him dress himself, and try on his vest, which is the King’s new fashion, and will be in it for good and all on Monday next, and the whole Court: it is a fashion, the King says; he will never change.”

On Monday, October 15, Pepys recorded “This day the King begins to put on his vest, and I did see several persons of the House of Lords and Commons too, great courtiers, who are in it; being a long cassocke close to the body, of black cloth, and pinked with white silke under it, and a coat over it, and the legs ruffled with black riband like a pigeon’s leg; and, upon the whole, I wish the King may keep it, for it is a very fine and handsome garment.“

A gentleman in knee-length coat, long vest, and breeches, 1670. Source: Cunnington.

Fashion — even by royal decree — doesn’t change instantly, but after about 1670, petticoat breeches and short jackets were being replaced by the knee length coat, less voluminous breeches, and a waistcoat or vest that gradually got shorter — in relation to the coat — over the 18th century.

King Louis XIV and Family, painted in 1711. From Boucher: 20,000 Years of Fashion. The King’s vest matches his brown coat and breeches; the man at right wears a brocade vest with a red coat and matching red breeches.

“Attempts have been made to trace to Persia the origin of the coat which about 1670 ousted the short doublet from fashionable wardrobes. It is true that the first coats closely resembled the contemporary Persian garment, which in its turn had not changed much from the ancient Persian coat …. It is true also that Sir John Evelyn returned from Persia in 1666 enthusiastic about the native costume. (Pepys made an entry about it in that year.) Nevertheless it was four years after that date when the new garment actually replaced the short doublet at both French and English courts…. Be that as it may, here was a coat, and the history of masculine dress from that day to this is largely a record of the changes rung up on that essentially unchanged garment.” — Lucy Barton, Historic Costume for the Stage, page 276.

The progress of the three piece suit introduced by Charles II in 1666 is a gradual evolution. The vest gradually got shorter:

The vest or waistcoat of 1735 was still quite long, although not nearly as long as the coat. Cunnington.

This gentleman’s vest is still thigh length in 1785. (Boucher.)

During the French Revolution and the Directory, vests approached the waist. (Kybalova et al: Encyclopedie illustree du Costume and de la Mode.)

In the drawing above, the coat is cut away to show more of the legs — still in knee breeches. But the radical Revolutionaries were called the “sans culottes,” because they didn’t wear breeches. They wore long trousers (pantalons.)

A “sans culotte” revolutionary drawn in 1793. Note his wooden shoes, or “sabots.” Source: Kybalovna, et al.

An actor dressed as a revolutionary, dated 1792 by Kybalova.

The coat is cut away to show just a bit of vest (stopping at the waist) and to expose tight, pale-colored breeches. (Cunnington) This is the ancestor of the modern “White Tie and Tails” formal wear.

After the revolution, when there was once again a French court, a gentleman might wear knee breeches for formal occasions and pantalons for more casual dress.

Two gentlemen, circa 1810 1811, from Kybalova’s Enc. illustree du Costume. The vest/waistcoat at right just reaches the waist. The pantalons are very tight.

In this illustration from 1872, Charles Dickens (left) wears a short frock coat with a waistcoat of different fabric and long trousers. Benjamin Disraeli (right) is wearing a suit of “dittoes:” a three piece suit made from one fabric.

Victorian gentlemen. The “suit” could be all one fabric (right) or two or three different fabrics. 1872. Cunnington.

These suits from 1933 came with matching vests. Esquire magazine.

But, for less formal or country occasions, a contrasting vest could be worn:

Gray suit worn with contrasting vest. Esquire, April 1934.

The King of Denmark also wore a contrasting vest — in 1785. (Styles worn at royal courts tended to be slow to change. Knee breeches were still worn at the British court in the 1900s, as this cigarette card from 1911 shows.

Clothing actually worn by King Frederick of Denmark, 1785. From Boucher. (museum photo, Rosenborg Castle.)

There’s a very good article about King Charles II and the introduction of the “Persian vest” here.

Sources for images in this blog post:

Francois Boucher: 20,000 Years of Fashion

Phyllis Cunnington: Costume in Pictures

Lucy Barton, Historic Costume for the Stage

Ludmila Kybalova et al, Encyclopedie illustree du Costume et de la Mode (1970)