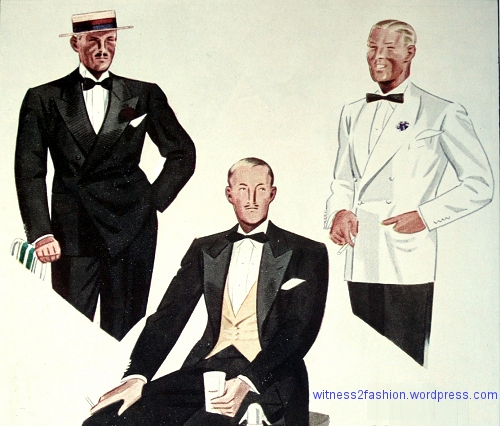

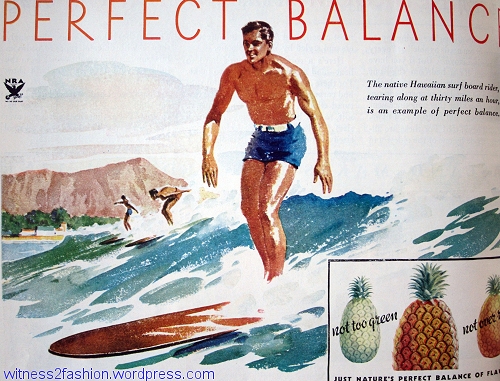

One of many pages of men’s fashions from the first issue of Esquire magazine, Autumn 1933.

A good costume designer is just as interested in men’s clothing as in women’s, with good reason: There are far more parts for men than for women in plays, movies, and television.

But dating men’s 20th century clothing is difficult for a number of reasons, among them a slower rate of change (men don’t buy a new suit for every new occasion, but wear them for years) and the subtlety of the changes (a quarter inch in the width of a lapel or a necktie, two versus three buttons, etc.) And not many theatres can afford a full-time tailor.

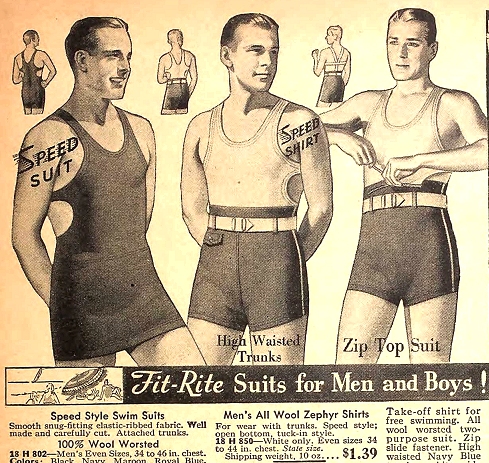

Men’s suits from Sears, Spring 1938 and 1948. Click to enlarge.

Often, for budgetary reasons, “close is good enough” on stage because the audience probably won’t know the difference between men’s suits from 1938 and 1948 — although the difference in women’s fashions from those years would be clear.

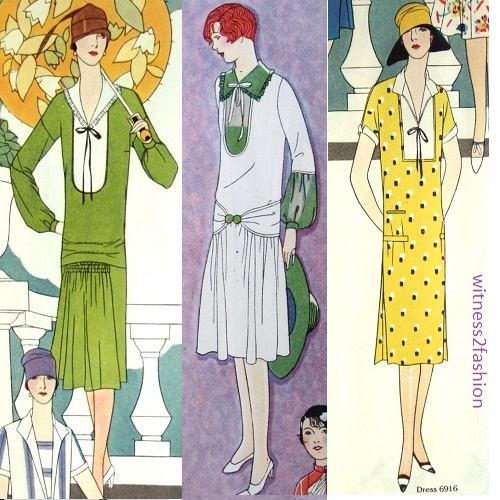

Women’s suit patterns, 1938 and 1948. The silhouette is very different. Click to enlarge.

I feel bad about neglecting men’s fashions in this blog. However, this month I came across the very-first-ever-issue of Esquire magazine. Considering that it appeared in the depth of the Great Depression, when other magazines were becoming shorter (not enough advertisers) and eliminating color pages to save printing costs, who would expect to find 14 full-color pages of men’s fashion in Esquire’s premier issue? But there they were — along with cartoons in color! (Fashion illustrations by L. Fellows.)

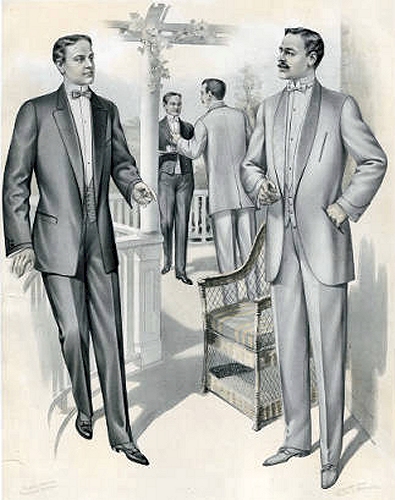

“This Our New York,” cartoon by Howard Baer. Esquire, Autumn 1933. Public transportation brings together a range of ages and ethnicities — all wearing hats and gloves. His flashy clothes (and appraising stare) imply that the man on the right is not a gentleman.

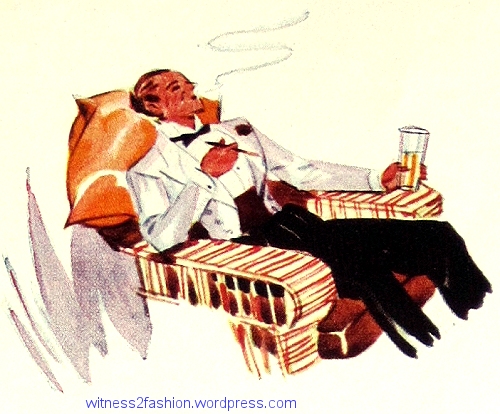

The first issue was a quarterly — Autumn, 1933. In 1934 Esquire became a monthly magazine. Like Delineator magazine, Esquire aimed at a middle-to-upper class reader. Just as Delineator focused on what was worn in Paris, Esquire was focused on successful, East Coast, Ivy League, business and professional men — and those who wanted to imitate them. Many of the clothes are illustrated on older men of distinction; illustrations of sportswear (riding, skiing, and spectator sports like racing) assume that Esquire readers are far removed from breadlines and soup kitchens.

New Looks for Men in 1933

Some trends described as new to men’s fashions in fall of 1933 were the appearance of brown suits in business settings, rougher-textured and harder-wearing wool suits and coats (a nod to the Depression), and the shirt collar fastened by a pin. Colorful — and patterned — business shirts with white collars and cuffs were pictured often. It’s not certain that every fashion Esquire suggested became mainstream — just as few people actually wore Vogue editorial fashion. But the opportunity to see 1930’s color combinations, including advice on coordinating hats and shirts and ties, socks and suspenders and handkerchiefs, makes me very happy! Here’s what I learned from just four pages:

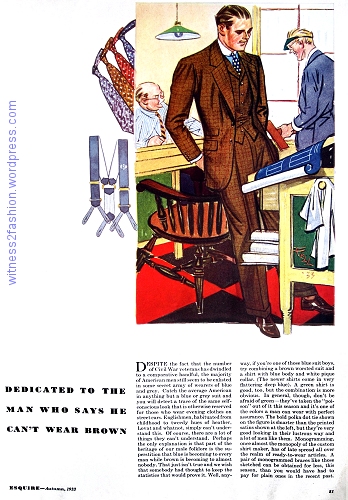

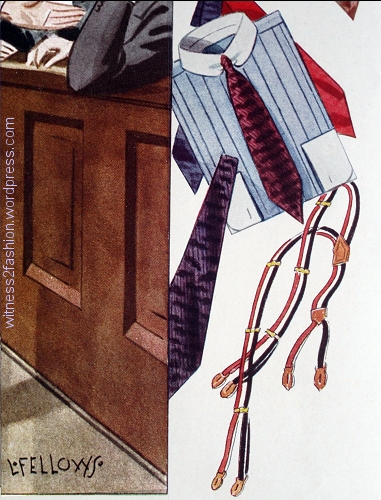

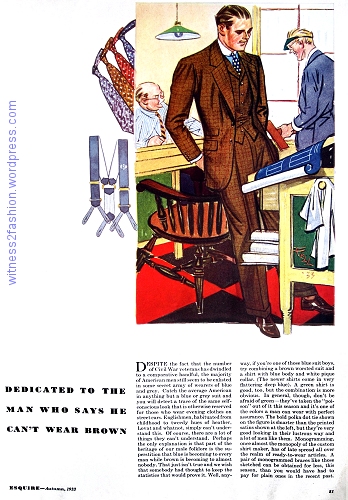

The Lawyer

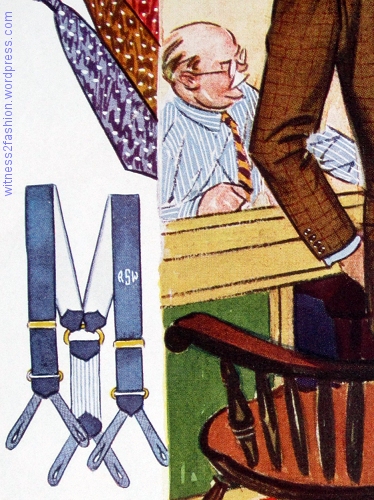

Navy double-breasted suit and accessories, Esquire, Autumn 1933, p. 82.

This traditional double-breasted, navy blue suit “will never get you into the headlines as the Beau Brummel of your time,” but for the man who is not sure that his “taste in colors [is] to be trusted, sticking to plain blue is the most reliable way” to look smart. “You may not be resplendently right, but a least you can’t be clamorously wrong — you can wear almost anything with a blue suit.” Esquire recommends a colored shirt with white collar and cuffs. The one he’s wearing has bold stripes. Colored pocket square.

For wear with the navy suit, “self-figured” ties, gray Homburg hat, and a blue shirt with white pique collar and collar pin. Esquire, Autumn 1933.

“The white pique collar that comes with the shirt should be of the new model that provides eyelet openings for the collar pin.” You can wear any of the self-figured ties sketched in the panel of accessories.” “The hat is the correct gray Homburg.”

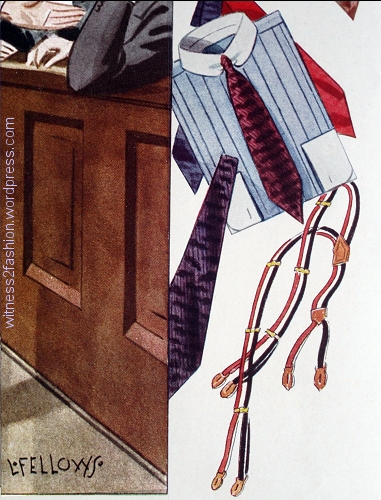

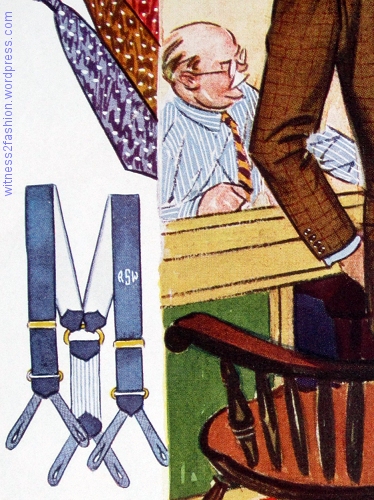

“The newest thing in braces [suspenders] is the double braid in contrasting colors.”

“The newest thing in braces [suspenders] is the double braid in contrasting colors.”

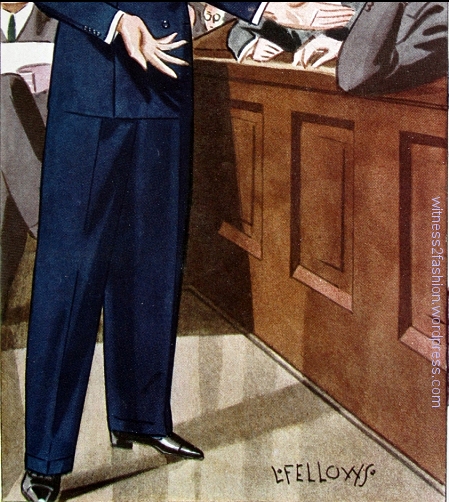

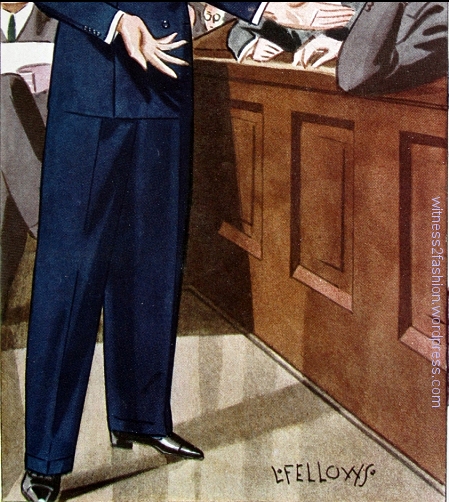

The full-legged, sharply creased suit trousers taper to a cuff.

The full-legged, sharply creased suit trousers taper to a cuff.

Cuffed, tapered trousers, 1933. They are exactly the right length to flow smoothly without a “break” [wrinkle] over the instep. Illustrations are by L. Fellows.

I find it interesting that the man in the navy blue suit is shown pleading a case in front of a jury; in

Dress for Success (1975), John Molloy recommended that trial lawyers wear navy blue suits, because surveys showed that working-class jurors distrusted men in gray suits (too much like bankers.)

The Architect

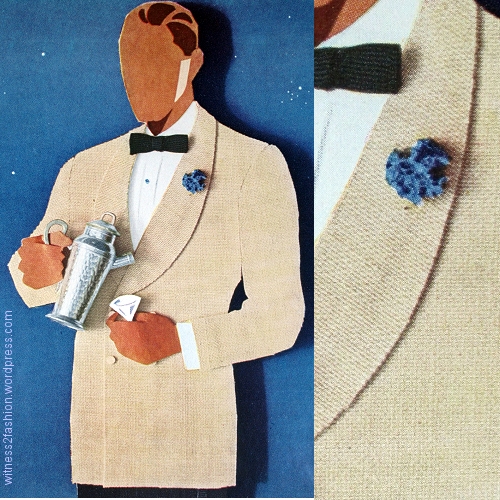

Brown worsted checked 3-piece suit, blue shirt with white collar and cuffs, and polka dotted or printed satin tie. Esquire, Autumn 1933, p. 81.

This young architect is wearing a three-piece brown suit with a small windowpane check. (For comparison, click here to see a 2016 three-piece checked suit — vest sold separately. The fit is very different, and the jacket very short.) Like the 1933 navy blue suit, these rather full pant legs are tapered and cuffed.

Tapered, cuffed suit trousers, Esquire, 1933.

His matching vest has a lapel. His two-button jacket has flap pockets (including a small “ticket pocket.”)

Esquire showed two brown suits in city settings; “Catch the average American in anything but a blue or grey suit and you will detect a trace of the same self-conscious look that is otherwise reserved for those who wear evening clothes on street cars;” Esquire blamed this on the “superstition that blue is becoming to everybody” while brown is not. “If you’re one of those blue suit boys, try combining a brown worsted suit and a shirt with blue body and white pique collar. (The newer shirts come in very flattering deep blue.)” All four suits have very broad, padded shoulders.

Two button suit with matching vest, which has a lapel; worn with blue shirt, white collar, and a selection of ties. Note the collar pin. Autumn 1933.

“The bold polka dot tie shown on the figure is smarter than the printed satins shown at left, …but lots of men like them.”

Monogrammed braces (suspenders.) 1933. Note the striped business shirt and rep tie worn by the older draftsman.

“A pair of monogrammed braces like those sketched can be obtained for less, this season, than you would have had to pay for plain ones in the recent past.”

The Doctor

A doctor wears a rough brown vested wool suit for a more informal appearance. Esquire, Autumn 1933, p. 87. Wide, tapering trousers and very wide shoulders.

More outdoorsy brown suits were recommended “for men whose business or profession makes an easy informal appearance helpful. The doctor, for example…. [Brown suits] resemble, as little as possible, the costume of the average undertaker.”

“With the new trend toward rougher textures, brown suitings … rough weaves, rough almost to the point of shagginess… have come to town.” [As opposed to being reserved for country wear.]

The doctor illustrated is wearing a “two button notch lapel modified drape model.” Notice the high waist and low crotch on the trousers, which are sharply creased and are cuffed at the tapered hem.

Two-button suit with matching vest, high-waisted trousers with cuffs, and “clipped figure” shirts. Esquire, Autumn 1933.

“The accessories … are selected as being especially well suited for wear with the rough suitings. The clipped figure shirting, long outside the pale of fashionable preferment, has come back with this new suiting trend, the slightly raised appearance of the fabric being especially appropriate with a soft rough suiting.”

“Spitalsfield” ties, 1933.

“The Spitalsfield [sic] tie is another revived favorite. In a tie of this type you can get away with bright colors without … gaudiness.” [London’s East End district of Spitalfields was famous for its silk weaving, thanks to an influx of Protestant French refugees after 1685.]

As for hats, the snapbrim is the only suitable model, but to be up to the times it ought to have the rather high tapered crown shown in the one sketched…. It is good in green or brown with a greenish cast.”

The Stockbroker

Gray double-breasted herringbone suit, without trouser cuffs and with a ticket pocket. Esquire, Autumn 1933, p. 93. Men’s waists were high.

This gray herringbone double-breasted suit is not quite traditional. “Town clothes… are undergoing many changes. Here we have the omission of cuffs on the trousers and the addition of a ticket pocket placed just below the line at which the draped model gives a slight waist suppression…. The herringbone pattern is enjoying renewed popularity with the trend toward soft rough fabrics in suitings for town and business wear. A plain shoe, in black or briar brown … with a simple toecap and no punching or pinking…”

With this gray suit, he wears a horizontally striped shirt with white collar and cuffs; matching solid necktie. 1933. Is that a glimpse of a matching herringbone vest?

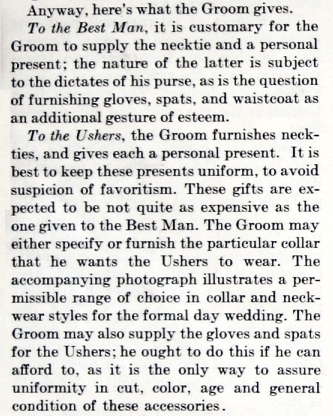

“… a demi-bosom shirt with cross stripes worn with a low front white laundered collar [detachable collars were still being worn]; and a dark solid-colored tie with a plain pearl stickpin — that rounds out … this formula for appearing to good advantage during the daylight hours. [For] men who have formed the habit of wearing foulard ties twelve months in the year, the new printed satin ties “have foulard prints, but wear much better.”

“Vertical striped hosiery” goes well with the suitings in rougher textured fabrics.

Trousers without cuffs (British “turn-ups”) worn with striped socks and suspenders (“braces”) that have “brace clips” to attach to your shirt. 1933

“Brace clips, attached to elastic cords, keep one’s shirt down.”

The number in his lapel, the slips of paper on the floor, the hurrying messenger — all are signs that this man works in the stock exchange. This photo confirms the background scenery, and this one shows exchange members with numbers in their lapels.

More 1930’s menswear to come ….