It would be remarkable to open a grave and find well-preserved clothing from 600 years ago, but the wool blouse, string skirt, and belt of the “Egtved girl” found in Denmark are nearly 3400 years old!

image from Reddit Posted by u/Alexaalexa97

There are many documentaries on YouTube about this wonderfully preserved clothing from 1373 BCE, with an actress wearing and demonstrating moving around in carefully recreated copies of the outfit. [ Note: Some of the speculation about the original wearer’s life and travels has been re-evaluated as more scientific information becomes available. Apparently the soil samples used to trace her origins were based on samples from land contaminated by modern agriculture and modern chemical fertilizers. ]

But seeing these clothes being worn (and danced in) is marvelous. https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-bronze-age/the-egtved-girl/

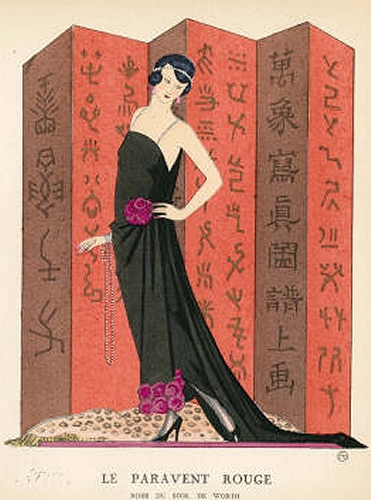

Egtved girl in reproduced clothing, courtesy of Nationalmuseet i København

The outfit, including a decorative belt that wraps twice around her body and has a round shield/sun disk looks surprisingly modern in this era of cropped tops and very short skirts. See a recreation being worn here.

The “see through” wrap skirt is a recognizable descendant of skirts seen on pre-historic “Venus” statuettes. Elizabeth Barber has written about these “Venus’ girdles.”

If you want a close look at the way these clothes were reproduced by experimental archeologists, here are some YouTube videos:

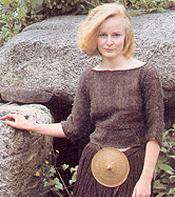

Sally Pointer has posted many videos of her work on prehistoric textiles, including how to make string for cords, nets, and clothing from nettles (!) which are processed much like flax is processed to make linen. If you are interested in prehistoric textiles, subscribe to her YouTube channel. Her videos on reproducing the Egtved girl’s clothing are filled with good images of the historic clothing and her reproductions, being modeled by a modern young woman. Here is a long list of her videos: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL5zgizOgAtq211QucFDShmbK1CieFOClX

My own experience of stinging nettles comes from walks in England, and it’s inspiring to think pre-historic people used this seemingly unfriendly plant for textiles and food! Once archeologist Elizabeth Barber (in Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years) pointed out that half the historic record was long ignored because textiles and wooden objects rarely survive, I became very conscious of the fact that we speak of “hunter-gatherers,” but we find much more evidence of hunting (stone arrowheads, bone fishing hooks) than we find of gathering — which includes baskets, ropes, fishnets, and clothing. If you’ve ever tried to carry ripe blackberries back to your campsite in your hands, you’ll appreciate that prehistoric people had to figure out a way to carry large quantities of fruits and grains! They also had to carry water, probably in leather bags or tightly woven baskets. And of course, they had to carry babies while keeping their hands free. I can’t imagine that pre-modern nomadic people didn’t take their painstakingly made stone tools with them while following herds and moving to summer or winter camps. [In fact, the man who lived about 5000 years ago and was found preserved in ice — now called Otzi — had a leather pouch on his belt. Penn Museum has an excellent article about him — and his clothing.] As important as spears and axes were needles, scrapers, and awls. An excavation in what is now Florida shows that Native American women were weaving textiles from palmetto fibers 7000 years ago. They were buried with their needles and other tools.

If you have time, this article from The Guardian explains how much we have underestimated the skills of pre-historic women.

Experimental archeologist Ida Demant has also reproduced the skirt and Emma Stockley shows you a quick pre-historic top. This top is not based on the Egtved girl, but on the top worn by an older woman buried at Borum Eshoj, Denmark. The oak from which her coffin was made dates to about 1350 BCE. This blouse surprised me because it required a tool which could cut fabric, instead of using rectangular woven pieces stitched together. (And, yes, this video uses scissors and a sewing machine!)

Vintage News has lots of ads but some good photos. The Egtved girl’s clothing was wonderfully well-preserved because she was buried in an oak coffin. Only her hair and teeth remained; she is not a mummy. Her coffin and possessions are in the National Museum of Denmark.

Other YouTube Videos that have cheered me in October:

Other YouTube Videos that have cheered me in October: