I’v been wanting to recommend this little book, Cut My Cote, for a long time, and, since I showed some Victorian era men’s shirts in a recent post, this seems like a good time to share some things Cut My Cote taught me about the evolution of the shirt.

Shirt made by Elizabeth Wild Hitchings in 1816. Metropolitan Museum Collection.

“This shirt was created, from the linen fiber to the finished garment, by the donor’s great-grandmother, Elizabeth Wild Hitchings, for her husband Benjamin Hitchings, a sea captain, in 1816.”

Cut My Cote, by Dorothy K. Burnham, is more of a pamphlet than a book, but its 36 pages are packed with useful diagrams and thought provoking information. For me, it was one of those “whack on the side of the head” books, because I had simply never considered how precious cloth was in the pre-industrial age, or how garment construction was influenced by the size of the handwoven cloth available. Making clothes from Burnham’s diagrams is a real education.

This book expands on some themes from Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, by Elizabeth Barber. Barber, an archeologist and a weaver, estimated that it takes a woman seven hours to hand spin enough thread to weave for one hour. For the woman spinning and weaving and sewing a linen shirt like the one above, every scrap would represent days of labor. You can understand why “zero waste” clothing is not a new idea.

Diagram of 16th c. man’s shirt, by Dorothy Burnham, showing how not a single inch of the handwoven linen was wasted. From Cut My Cote. Please do not copy this image. The cloth was 27 inches wide.

In the shirt above, the sleeves (B) narrow from below the elbow to the wrist. The triangles of fabric (C) trimmed from the lower part of the sleeves are used to widen the upper part. The neckline is slit straight across, and gathered into the collar at front and back. This gives ease across the back. (Modern shirts have a center back pleat for the same reason.) Notice how similar it is to that shirt made by Elizabeth Wild Hitchings nearly three hundred years later.

“I shall cut my cote after my cloth.”

Burnham examines this proverb and finds it true: “I shall cut my cote after my cloth.” ( Haywood’s Proverbs, published in 1546) You may have heard a variant of the proverb:

“You must cut your coat to fit your cloth.”

The size of the cloth often dictates the shape of the garment. Using her measurements of rare surviving garments, Burnham charts their cutting patterns. In examples that trace the development of the European shirt, for instance, you can see how reluctantly the cloth is cut at all, and how every inch is utilized.

The Loom and The Shirt

Burnham explains the various types of looms used from place to place, and how the physical requirements of the loom (width, portability, number of weavers) dictates the width of the cloth. Ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt [all slave-owning societies, as it happens] used very wide, vertical or horizontal looms; some needed two weavers passing the shuttle back and forth. The Greeks wove big, wide pieces of cloth, and wore them sideways, wrapped around the body with one selvage as a hem and the other at the top, usually pinning (rather than sewing) the garment at the shoulders. Excess length was controlled with belts, or by folding the top down, or both (below right.) It didn’t need cutting or sewing.

Greek charioteer, ca 475 BC; Roman dancing girl, before 79 AD.

Nomadic societies had to use looms that were portable and easy to set up. Sometimes a waist strap (or back strap) loom was used (Click here to see one being used.) When fabrics began to be worn vertically, instead of having the selvage as a hem, their width was dictated by the weaver’s reach when passing the shuttle from one side of the loom to the other. Since shirts made from narrow cloth were also worn very long, added width was needed for walking, so the sides had to be open at the hem, or the front and back were slit and godets inserted, as below. The fabric for this 13th century shirt was only 22 inches wide. Fabric (C) left over from the sleeves (B), which narrow toward the wrist, is used for godets (C) to widen the bottom of the shirt.

Burnham’s diagram for a 13th century French shirt. The wedges (C) cut off the fabric used for sleeves have been inserted into the bottom of the shirt front and back. Please do not copy this image.

This drawing of a medieval farm worker shows a similar garment, with tapered sleeves and a very full skirt.

Harvesting barley in a long, belted, shirt-like garment. Late 1300’s. From 20,000 Years of Fashion, by F. Boucher, p. 199.

Shirts for the 1700’s

Late 18th c. shirt in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

I have made late 18th century shirts like this one using Cut My Cote as one source, and, while perfectly authentic, they did not always behave well on sweaty actors and singers. You can see that the shoulders of the shirt are much wider than the shoulders of the wearer, and in the diagram there is no shoulder seam. Even on a motionless mannequin, the shoulders fall forward, twisting the sleeves.

Also, when the neckline is cut as a straight line, like this one …

Shirt, late 16th c. Diagram by Burnham. Please do not copy.

… it doesn’t take into account some facts about the human body. First, flat rectangles of cloth are relatively two dimensional; we are three dimensional. Second, we are not symmetrical when seen from the side.

Left, based on an illustration from Walt Reed’s book The Figure; Right, based on an illustration from Drawing the Head & Figure by Jack Hamm.

Our necks are lower on the body in front than in back. The measurement from the base of the neck to waist (CF measurement) is always shorter than our Center Back measurement (CB). If you cut your shirt’s neck opening in a straight horizontal line, the opening will be forced down in the front, and the shirt will twist on the body. The shoulders of the shirt will want to move forward, while the back rides up. (Actors will be more comfortable with a modern curved neckline on an otherwise “period” shirt.”)

Another problem that had to be solved was the trapezius — the muscle that connects your neck with your shoulder.

Geometrical stick figures (top) and a stick figure adjusted to treat the neck and trapezius more realistically (bottom). Photo from Walt Reed’s book The Figure.

It took a long time for most shirt makers to solve these problems, although this woman’s smock from 1630 has a triangular gusset at the side of the neck; that was part of the solution.

This shirt, which belonged to British banker Thomas Coutts, has triangular pieces at the neck, either side of the collar.

Early 19th c. shirt belonging to Thomas Coutts, Metropolitan Museum Collection.

This 19th century shirt with a neck gusset was collected by a friend.

Linen shirt, 19th century. The collar has a gathered triangular gusset at each side. inserted in the straight, slit neckline.

The triangular gusset is an attempt to solve the problem of the trapezius. It just didn’t go far enough.

The collar, hand sewn, is a finer fabric than the shirt’s body.

This shirt, from the same collection, has a shoulder yoke and a different way of using a triangular gusset:

19th century shirt with a yoke across the shoulders and a gusset below the yoke. Apparently the shirt body was cut straight across, but did not match the shape of the yoke without piecing. The neckline seems to be curved in front.

These collars with a wide gap between the wings were seen from the 1820s through the 1850s, persisting among older men. They could be starched and worn turned up, or worn turned down.

Shirt collars with a wide gap in front: a fashion plate, 1849, a sketch by Ingres, 1826, an older man, 1859, and Ingre’s self portrait at age 79, 1859.

This shirt, also owned by Thomas Coutts, has a yoke. So did the shirts worn by Mississippi boatmen in the 1840’s and 50’s, as painted by George Caleb Bingham; their shoulder seams drop far down the arm. (Shirts were one of the few ready-made garments available. But they were not sized to fit before the Civil War, when statistics that made standard sizing possible were collected.) The boatmen’s shirt size was probably dictated by the width of the cloth available.

The Jolly Flatboatmen, painting by George Caleb Bingham, 1846.

The problem of the too-high-in-front neckline was solved by wearing the shirt unbuttoned at the throat. There are no other buttons, except at the wrists, and shirts were pulled on over the head.

Mississippi Boatman by George Caleb Bingham, 1850.

Another problem for shirtmakers was that, if the sleeves were tight, it was hard to raise your arm.

Photo from Erik A. Ruby’s book The Human Figure. If your sleeve was tight, raising your arm like this pulled your shirt up several inches.

Some cultures — like Japan — left the underarm seam open. Europeans wanting to wear tighter sleeves without losing the ability to raise a sword or a tool, wore a very full sleeved shirt underneath a tight outer sleeve that was attached only at the shoulder, or tied on just at the top.

A young man by Memlinc, and a young lady by Ghirlandaio. Both are late 1400’s. Her sleeve is also open at the elbow, so she can bend her arm easily.

But the best solution was a square gusset (C), inserted in the underarm seams so that the bias stretch would accommodate movement.

Burnham’s diagram of an early 19th century shirt with underarm gussets (C) and neckline gussets (F). Please do not copy this image.

The shirt above, diagrammed by Burnham, was one of several owned by Thomas Coutts (d. 1822); the survival of his large wardrobe is a boon to historians.

Victorian era shirt with underarm gusset. It also has neckline gussets, like the Thomas Coutts shirt Burnham diagrammed.

Neck gusset in a Victorian era shirt.

Neglected Treasures

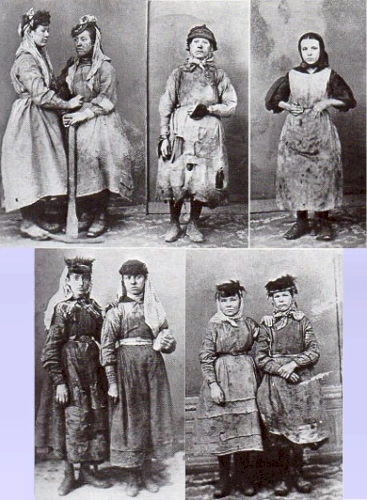

For the most part, shirts are not beautiful; they are not collected; they get worn out and used as cleaning rags; they get passed down to be worn as work clothes, instead of being wrapped in tissue and passed down as heirlooms. That is why very old shirts in very good condition are really, really rare! And a very old shirt with provenance can end up in a museum’s Costume Collection.

This wedding shirt from 1841 has a curved neckline; like a formal dress shirt, it opens down the back. It’s in the Victoria and Albert collection.

I’m not sure whether the dealer who bought my friend’s collection had any idea about how rare documented Victorian era shirts are. Here for example, is a lace embellished shirt that my friend was able to document, because it was made for a wedding and remained in one family.

A wedding shirt of Davenfort Harrold, dated to 1871. The neckline curves and is deeper in front. A separate collar could be worn.

Eureka: Shirts That Fit

I think the ultimate solution to making shirts that fit arrived along with the industrial revolution, when spinning and weaving became mechanized, lowering the price of cloth. Before that, as Dorothy Burnham says, “an extreme economy of material was practised in the cutting of traditional garments…. In ancient times, weaving far outstripped the techniques of cutting and sewing….”

Once people realized that cut cloth will not unravel after it’s been sewn, and that a certain amount of wastage is preferable to a poorly fitting shirt, the problems of the neck and trapezius fit were solved by a diagonally cut shoulder seam and a curved neckline that was cut deeper in front than in back. (The triangular neck gusset was, in a way, included in the new seam across the shoulders, which creates a triangle.)

Using statistics collected for the manufacture of military uniforms, a range of sizes and a closer fit became possible.

Shirt diagram from the Cutter and Tailor. It is essentially a modern shirt.

This heavy cotton flannel shirt, made in Sherborne, England, ended up in California. It is factory made, with a curved neckline, sloping shoulders, and a double layer of fabric for warmth. But its one-size-fits-many sleeve length had to be adjusted with a tuck. (Office workers could shorten their sleeves with a sleeve garter.) Also, like earlier shirts, this one pulls on over the head.

Vintage flannel factory-made work shirt, probably from Sherborne, England. The label says “N. E. Strickland & Co., Shirt Specialists, Sherborne.” Strickland shirts are still being made, but not necessarily by the same company.

There is a good review of Cut My Cote at The Perfect Nose. (Click here). It shows several different illustrations from the book and encourages the stitcher to dive in and use them instead of patterns — “mark it onto your fabric in chalk/ marker and have at it with ruler and rotary tool.”

I have done this (using a #2 pencil and muslin), and I learned a lot about the evolution of the shirt from making smocks, blouses, and shirts from Cut My Cote. My old copy was covered with measurements in pencil! You can find used copies for about $15.00 — Click here. — Or you could buy it new from The Royal Ontario Museum, which has kept it in print since 1973! Cut My Cote at ROM– Click Here.

For serious research into 18th century and early 19th century shirts, follow the links at 18th Century Notebook. An entire list of links to shirts in museum collections can be found by clicking here.

The TwoNerdyHistoryGirls wrote about 18th century shirts (and why the hems were so long — ick!) here.

It’s easy to see why this 1630 embroidered smock at the V & A Museum didn’t end up as a dishrag. And its

gorgeous blackwork embroidery probably saved this going-on-500-year-old Tudor shirt, circa 1540. It’s in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Read more Here.

But spare a thought for the uncollected, hand spun, hand woven, hand stitched, everyday shirts that were made and worn and finally worn out.