It’s always hard to look at a vintage ad or catalog, see a pair of shoes for $6.50, and figure out whether they were expensive or affordable or really cheap at the time. A while ago, I found several articles about living on $18 per week in the 1930’s. Click here to read more about them. I’ll be citing some of the same charts here.

I’ve been looking through JoAnne Olian’s book on the B. Altman catalogs from the 1920’s. I was surprised by how high Altman’s clothing prices seemed, especially early in the decade. Then I remembered that I have some articles about clothing budgets in the 1920’s, which might give me a better idea of nineteen twenties’ clothing prices.

I decided to compare the nineteen twenties’ and thirties’ budget advice, and see if I could follow it by “shopping” at Sears.

I was struck by one similarity: In both 1924 and 1936, a college educated office worker — female — could expect to be paid “$18 per week.” So she probably wouldn’t be shopping from the B. Altman catalog; nevertheless, trying to look nicely dressed for work was a real concern.

This woman earned $18 per week in 1924:

“…It is necessary that I at all times look well. My wages are figured at the rate of forty cents an hour, which usually averages up to eighteen dollars a week.”

This woman earned $18 per week in 1937:

“… For several years I could not expect to earn more than $18 a week, even though … I was a bit above the average beginner. Therefore my small salary would just about pay my board and keep me in lunches and carfare with nothing left. I needed new clothes [for] the office … because my dress was so shabby.”

Woman’s Clothing Budget in the 1930’s

In 1936, this article asked “Can a college girl dress on a dollar and a half a week?”

“What Can A Girl Live On?” Woman’s Home Companion, Oct. 1936. Total clothing budget for the year: $76.55, about one month’s salary.

It concluded that . . .

. . . A college graduate making $20 a week in 1936 could afford to spend just $78 a year — $1.50 per week — on clothes. “By being economical she can live decently and comfortably on seven hundred and fifty dollars.” (In theory, she would also be able to save over $100 per year, and/or take a vacation! Or so they said.)

Woman’s Clothing Budget in the 1920’s

The stenographer who wrote to Delineator magazine in August, 1924, asked how a woman with an office job could live — and dress well enough to satisfy her employers — on $18 a week.

That’s right: The salary of a female office worker was exactly the same — $18 per week — in 1924 and 1936. But in 1924, The Delineator’s experts reached a somewhat different conclusion about her necessary expenditures on clothing.

In 1924, $3.00 per week was allowed for clothing purchases — twice as much as in 1936. But in 1924, she needed much less for food and lodging (50% of her income) than in the thirties (62.5%.)

Comparing a Working Girl’s Budget, 1924 and 1936

I’m not enthusiastic about the way Woman’s Home Companion rounded $18 per week up to “$80 per month or $960 per year,” so I’ve compared percentages of income as stated, and lightened my derived figures on this chart.) I multiplied $18 by 52 weeks; WHC multiplied $20 x 4 x 12 months.)

Percent of income spent on Food, Lodging, and Clothes as budgeted in Woman’s Home Companion (1936) and Delineator (1924). Click to enlarge. It assumes living in a rented room, probably without a kitchen, and eating many meals out.

Perhaps, during the Depression, food cost more, leaving less money for clothing? Or had mass produced fashions become much more affordable?

Just for fun, I tried to find comparable items in the Sears Roebuck catalogs for 1924 and 1936, always choosing the cheapest similar items I could find to build a stenographer’s wardrobe.

Comparing a Working Girl’s Clothing Prices, 1924 and 1936

After browsing through Sears Roebuck Catalogs for 1924 and 1936, I’m struck by the decrease in some clothes prices. (In both cases, I looked for the very cheapest, not the mid-priced, garments.)

Skirts and Blouses

Wool & wool blend skirts from Sears catalog, Fall, 1936. About $2.00 each. The cheapest costs $1.00.

Inexpensive blouses were easier to find in the thirties, too.

Inexpensive blouses from the Sears catalog, Fall, 1924. Three of these cost less than a dollar each, but the most expensive is $3.48 — or more, in stout sizes.

Blouses from Sears catalog, Fall 1936. Six cost $1 each, and the others are less than $2. Could any woman make her own blouse for $1 (pattern 15 cents, thread, material @ 14 to 69 cents per yard, and buttons)? Maybe.

A typist could buy a skirt and blouse for less than $3.00 in the thirties, or about $4.50 in the twenties. But she’d have to settle for the cheapest clothes available from stores like Sears, not from upscale department stores.

Dresses suitable for the office:

The cheapest Sears dresses (excluding cotton housedresses) cost about $5.00 in 1924:

Wool dresses suitable for for the office, Sears catalog, Fall 1924. These three were among the very cheapest in the catalog, with many more dresses in the $8 to $16 range. The average price of the 11 dresses described on this page is $7.39.

In 1936, most Sears business dresses were made of Celanese, rather than wool, so they are not strictly comparable.

Dresses from Sears catalog, Fall 1936. The $5 dress on the right can be transformed with different necklines.

The cheapest nineteen thirties’ office dresses from Sears are about $4; and the variety in this lowest price range is much bigger than in the twenties. Office workers with only one or two dresses could make it seem like they had more by wearing different collars. (See One Good Dress in the 1930’s. ) Patterns for “change-about” dresses were also available. In 1936, the Woman’s Home Companion budget allowed a stenographer just four dresses per year, at $5 each.

Coats

You could find a winter coat for about $9 at Sears in the twenties or the thirties. Of course, a coat was expected to last at least two years.

Inexpensive coats from Sears catalog, Fall 1924. Pure Wool cost more than ” wool velour” or duvetyn.

Better Sears coats cost two to four times as much as these. In 1924-25, a fur-trimmed wool coat from the B. Altman catalog cost $110 to $115:

Better quality fur-trimmed coats from Sears could cost $49 in 1924. And our “stenographer” had only $156 to spend on an entire, year-round wardrobe — coats, shoes, dresses, hats, stockings at about $1 per pair (a big ongoing expense), underwear, etc.

In 1936, The Woman’s Home Companion budgeted $12.50 for a winter coat, every other year. These coats from Sears are a real bargain — assuming that they actually kept you warm and dry.

Shoes:

Inexpensive shoes from Sears cost much less in the 1930’s than in the 1920’s:

In 1936, The Woman’s Home Companion allowed a young woman four pairs of shoes per year — at $3 per pair.

Conclusion: A careful shopper, fresh out of college and earning $18 per week, could definitely make her clothing budget go farther in 1936 than in 1924 — but she would not be buying $6.50 shoes, and no one with an eye for quality would consider her well-dressed.

Skirts and blouses from the B. Altman catalog, 1925. The ensemble on the left cost $18.50, a whole week’s salary; the one in the middle was $24.25, and the one on the right cost $24.50.

No wonder there was a boom in clothing patterns and home sewing in the 1920’s — largely because early twenties’ dress styles were easier to make than ever before. Isaac Singer is credited with the invention of the installment plan, but you’d have to make a lot of clothes to amortize the cost of a sewing machine….

Sewing Machine Prices, 1925 and 1936

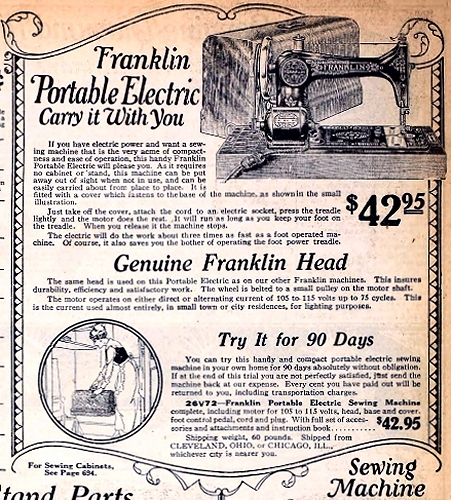

In 1925, you could get a treadle sewing machine from Sears for $33, or a portable electric for $43. By 1936, you could get an electric portable or table model from Sears for less than $30 — but inexpensive machines with the new, round shuttle cost more — about $38. In either year, we’re talking about two weeks’ wages for a working woman.

CAUTION: I did this study for fun, and tried to be accurate. But these samples are much too small for real scholarship. Since not all issues of Delineator and Woman’s Home Companion are widely available — or indexed — I wanted to let serious students of economics know that this material exists — and deserves a more thorough evaluation than I am capable of doing.