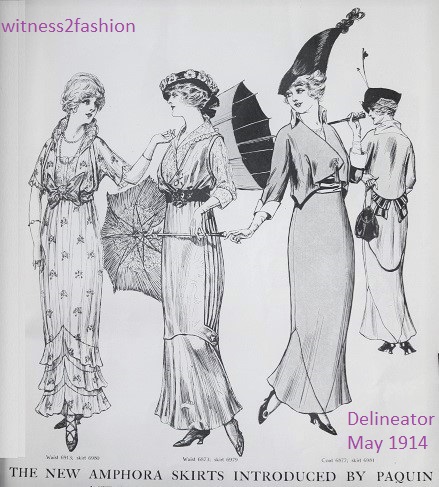

“The New Amphora Skirts Introduced by Paquin,” Delineator, May 1914.

“The New Amphora Skirts Introduced by Paquin” were fashion news in the summer of 1914. I didn’t understand, at first, because when I saw the word “amphora,” I first thought of the plain wine or oil jars that had pointed bottoms; many, many simple amphorae like these have been recovered by archeologists, especially from wrecked ships.

Amphora, terracotta; Greece, circa 3rd century BC. Image courtesy of Metropolitan Museum.

However, a Greek amphora (“jar”) can be highly decorated and have a base that flares out at the bottom:

Attic wine jar, circa 500 BC. Image courtesy Metropolitan Museum.

The “peg-top” skirts of 1914 — which get tighter at the bottom — accidentally resemble the plain, everyday jar, but were not called “Amphora skirts.”

Peg-top skirts (shaped like a child’s spinning top) narrow at the bottom, like this amphora. No wonder I was confused!

But the “Greek-vase” amphora skirt style “introduced by Paquin” resembles the more elaborate Greek wine vessel.

This is the type of amphora Paquin had in mind. Like the Greek vase, the skirts get narrow near the knee and then flare out at the bottom.

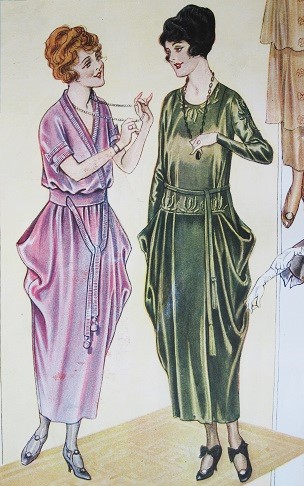

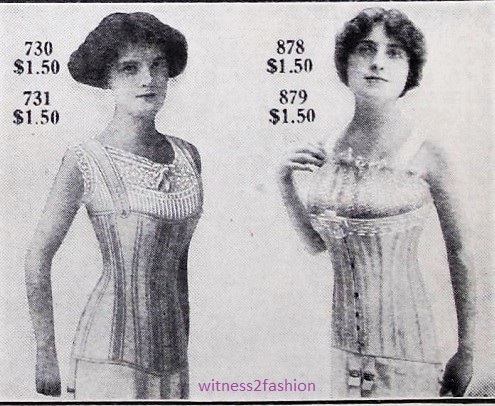

These Paquin-inspired amphora skirts have ruffles near the hem. Delineator, May 1914.

“Summer evening gowns will be the first to feel the influence of the new amphora or Greek-vase skirt. The softer versions of the amphora skirt, trimmed with ruffles of silk or lace are particularly pretty and they are delightful things to dance in. In fact, Madame Paquin had the new dances in mind when she designed her new skirt, a fact which accounts to a great extent for the width she has introduced in it below the knee.” — The Delineator, June 1914, page 19.

More amphora skirts introduced by Paquin.

“Most tub suits [i.e., made of washable fabrics] are made with straight gored skirts, the simpler peg-top models, or the new amphora skirt with a circular flounce at the sides. The latter skirt will be very popular for summer suits, for it is very easy to make and to launder, and is most comfortable for walking.” — Delineator, June 1914.

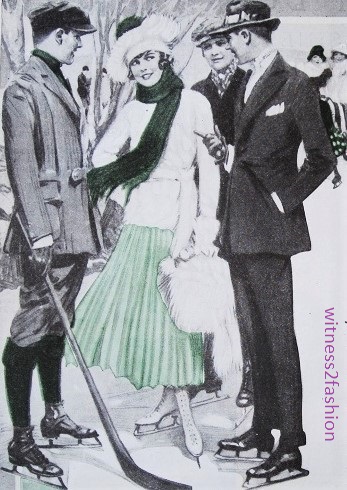

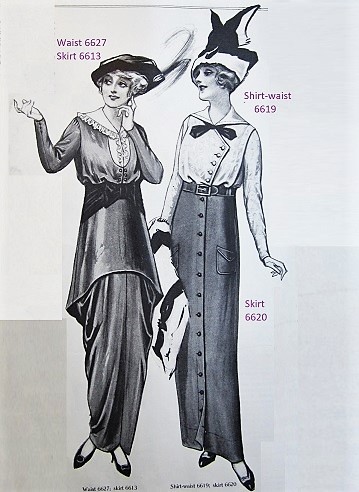

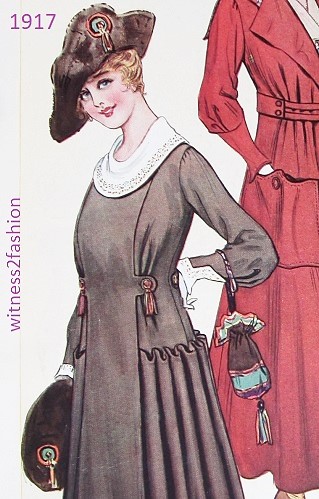

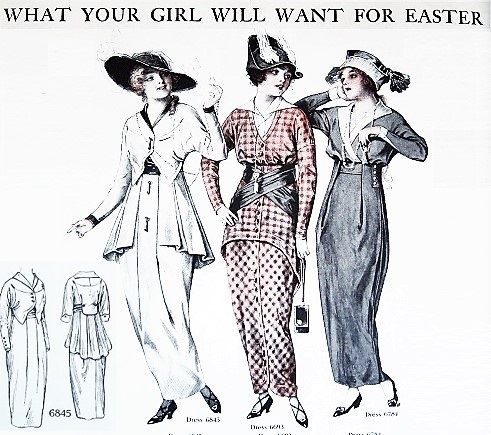

To give you an idea of why the “amphora skirt” was a change in direction, here are some images of the narrow-bottomed peg-top skirts that dominated early 1914 fashions:

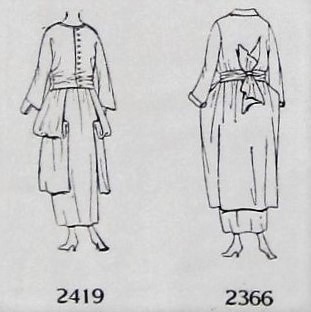

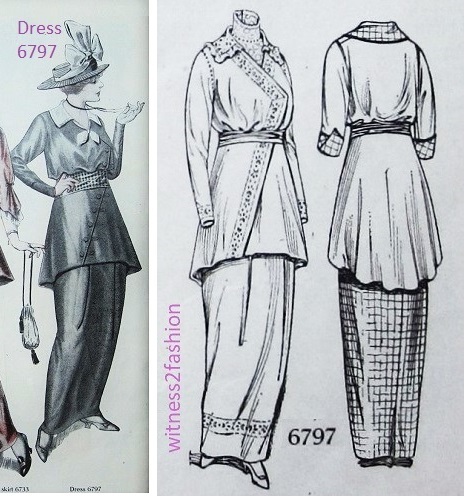

Butterick patterns from March 1914, Delineator.

Look at these restrictive, narrow-bottom hems:

Narrow hems, wide hips, create the need to take tiny steps. Peg-top skirts; March 1914.

Butterick peg-top skirt pattern 6818, from April 1914.

Butterick skirt 6770 is typical of the silhouette of early 1914. The center back has a small opening at the bottom, and probably in front, also.

How did they walk in these? Nos. 6818 and 6770 had slight openings. A back view of No. 6736 shows a slight opening in front and fullness in the rear:

Butterick skirt 6736 is narrow in front, but has ease for walking (or dancing) in the back. March 1914.

These peg-top skirts are not the “hobble skirt” which cartoonists lampooned earlier in the century, but they are descended from it.

This skirt was not made for long strides. Butterick 6914.

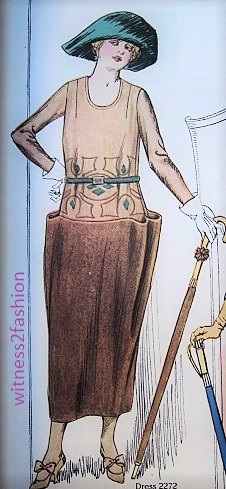

Two views of Butterick Amphora skirt 6978. June 1914.

Amphora skirt 6981.

Amphora skirts with lace or silk ruffles (left) and one with an insert, right.

Back views of 6979 and 6981. May 1914.

Alternate views of skirt 6980. May 1914. “The softer versions of the amphora skirt, trimmed with ruffles of silk or lace are particularly pretty and they are delightful things to dance in.”

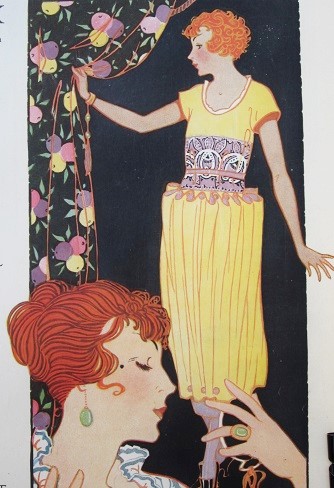

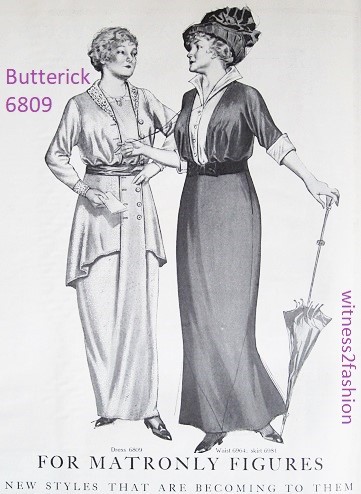

You didn’t have to be young to appreciate the greater movement possible with the amphora skirt:

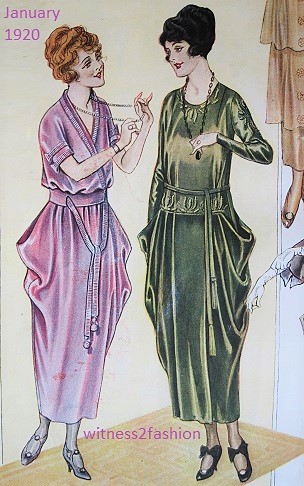

Two mature figures showing the skirt options available in Summer of 1914.

Fashion could accommodate more than one “look” in 1914.

It’s always nice to have a choice!

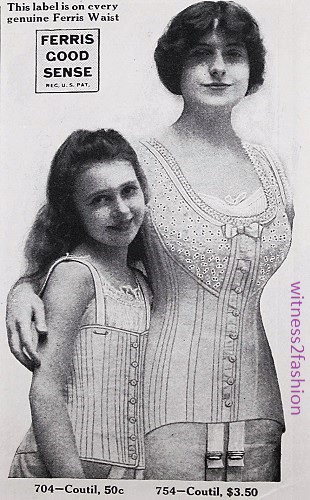

“While Paquin has been introducing the amphora skirt with its widened base, Cheruit and Premet have been experimenting with pantalets….” The Delineator, June 1914, page 19.

If you want to read more fashion predictions for 1914, click here.