Low heeled chic: Shoes from Sears, Fall 1966.

A few years ago I enjoyed watching a young woman in England on YouTube; she was a fan of the “Sixties” look and even went to great lengths to find authentic 1960s’ synthetic fabrics for the clothes she made. Her hair and makeup were appropriate. But I eventually stopped watching her because she kept getting the shoes wrong. Those Mary Quant dresses were generally not worn with high stiletto heels! (Very 1950s.)

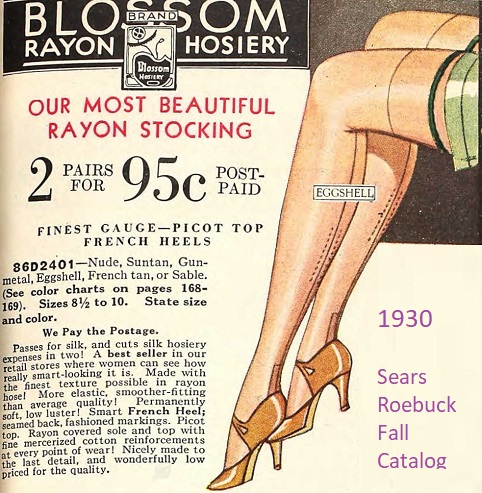

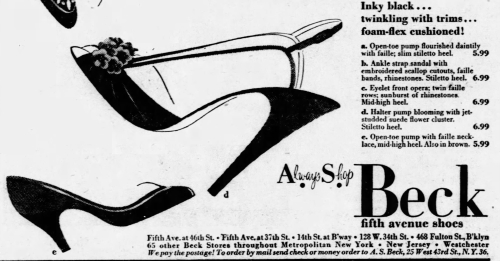

Stiletto Heels advertised in the New York Daily News, August 1953. Very 1950s. Not youthful.

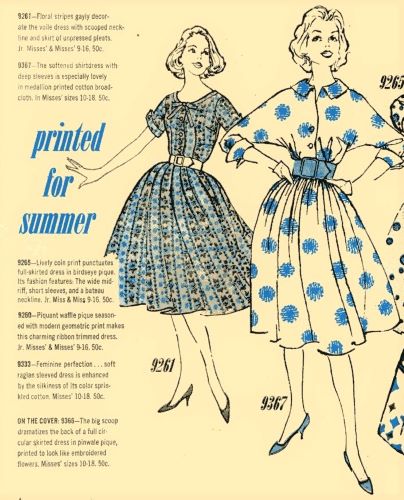

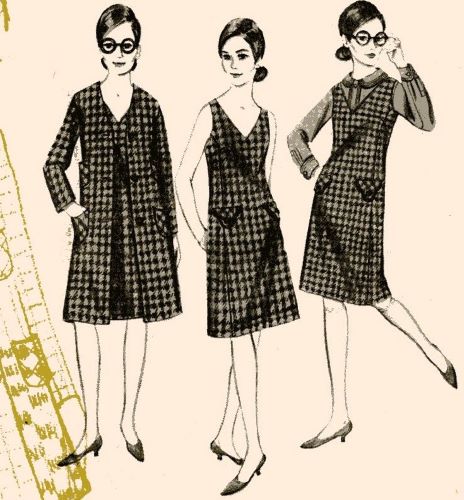

Butterick Fashion News features more Mary Quant patterns. April 1965. Notice the shoes.

These were callled “Kitten” heels, only about one inch high. Sears catalog, Spring 1966.

I was 20 years old, in college, in 1965. My friends and I were great Beatles fans. We loved youthful English Fashion. Of course, I’m not just trusting my memory about the shoes: “Since their introduction in 1950s, [stilettos] slowly went out style in 1960s, only to triumphantly return during 1970s when new “needle” style came into fashion. ” — from “History of Stiletto Heels.” The secret of the exceptionally narrow high heel was steel instead of wood, as this article from Popular Science explains.

These high heels are from 1958, when skirts still covered the knee — and 2 inches below it. From The Gazette, Montreal, 2/2/1958.

I had some of these “spike heels” in 1962 — not at all suitable for walking down steep hills in San Francisco! But in the mid-sixties, as the skirts got shorter, young women’s fashion shoes were actually comfortable.

Even with a Mary Quant suit, low heels were worn. BFN, April 1965.

Low heeled fashion shoes from Sears, Spring 1966.

My favorite shoes from 1966 were very similar to those green ones at the bottom. Mine weren’t from Sears, but they were bright pink. They went well with a couple of blue paisley dresses that had a touch of shocking pink as part of the pattern.

You could even wear flats (with half-inch heels) for all but the most formal occasions. BFN April 1965. Note the Mary Quant separates, including shorts, pants, blouse and skirt for a mix and match wardrobe.

Flats and Kitten heels from Sears, Fall 1967.

Those blue Mary Jane flats with the white trim and heels are definitely youthful chic.

1960s’ flats could have 3/4 inch heels, half inch heels, or 3/8 inch heels.

A variety of flats, Sears Spring 1966.

I also bless Quant for her “Empire” influenced dresses. BFN April 1965.

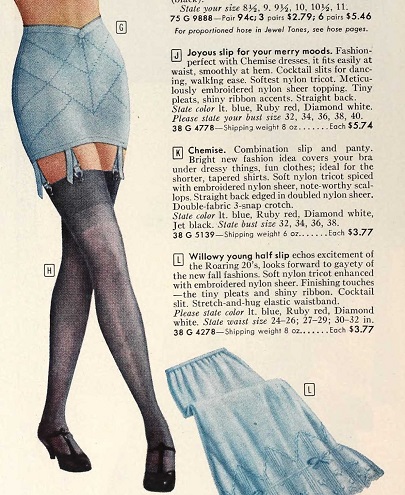

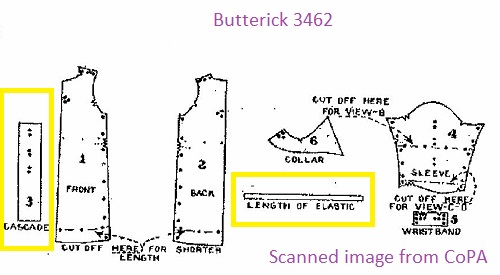

Quant played with ways of avoiding the tight-waisted fashions of the 50s. She introduced a high waist, like the one above, and a dropped waist evoking the 1920s.

Mary Quant pattern in BFN April 1965. Notice the shoes.

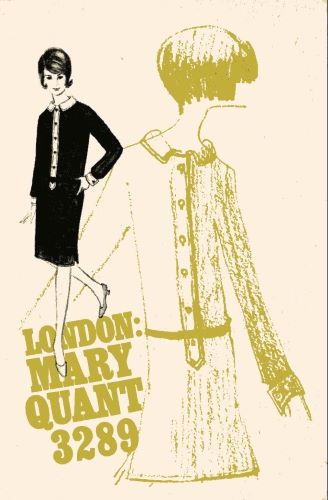

The neat white collar was a feature of many, many Quant-influenced designs, sometimes with a long center button placket or a variation on the necktie.

Another Mary Quant suit — this time with pants and a skirt to match the jacket and extend your wardrobe. BFN April 1965.

The matching trousers,1965.

Notice that 1960s’ sleeveless dresses did not always cut away at the shoulder. (I personally think that a sleeveless top that completely exposes the shoulder is more flattering.)

This is not to say that no young women wore very narrow heels in the 1960s, but they were generally not more than 2 3/4 inches high. They looked higher because the part of the heel that touched the floor was only about 1/4 inch square.

Narrow heels, but not “spiked heels.” These are all 2 3/4 inches high.

The college I attended owned an Italianate mansion built by a (temporarily) wealthy San Franciscan called William Ralston.

It included a mirrored ballroom, oval in shape, with wooden floors laid in a parquet pattern of dark and light. College dances were held there until people realized that those 1/4 inch square heels were destroying the floor. My father, who knew how to operate heavy equipment, once measured my 1962 spiked heels and did some math: a 130 pound woman wearing 1/4 inch wide heels exerted the same pressure per inch as a steam roller. Add to that the popular dance called “the twist” and it’s no wonder spiked heels were drilling holes in the century-old floor!

These heels from 1956 were lethal to some wooden floors. Image from Clarion Ledger, Jackson Mississippi, Sept. 1956.

So what did we wear with cocktail and formal dresses? Low, narrow heels. Continue reading