Ad for Gossard Bust Confiners, Delineator, March 1910, p. 250.

As discussed in the wonderful book Uplift, for centuries the breasts were supported from below, by a corset which pushed them up.

In the mid-twenties the uplift brassiere was invented, which supported the breasts from the shoulder (with the combination of bra straps and an elastic band below the breasts.)

In the mid-twenties the uplift brassiere was invented, which supported the breasts from the shoulder (with the combination of bra straps and an elastic band below the breasts.)

No drooping breasts (see the “BEFORE” dotted line) when you wear the A.P. Uplift bra.**** Ad from Delineator, April 1930.

But until the modern brassiere was invented,** women’s breasts were often subject to exaggeration (pushed up and padded in the early 1900s) or suppression — “confined” and flattened. All aboard for the history herstory tour…. *****

Women’s corsets for regular figures, 1907 and 1926. Both from Delineator magazines.

In 1907, the “big bust, big hips” S-curve figure was supported by a corset which covered only the bottom of the breasts.

The Nemo Self-Reducing Corset for stout women, Delineator, November 1907.

This was a problem for large- (even slightly large-) busted women. If the corset hits just a little too low, your breasts droop over the top, or slip out of the corset when you raise your arms. So, like wild beasts or prisoners, breasts needed to be “confined.” Something stronger than the chemise or camisole (worn under the corset) was needed

This Corslette provided boned support to large breasts. Ad, Delineator, November 1907, p. 856. Corslette made by Arthur Frankenstein & Co. [no, seriously.]

“It holds the bust high or low ….”

Text of the Corselette ad, 1907. It could be worn without the corset for outdoor sports.

“A boon for the stout. Reduces Bust Measure 3 to 4 inches [OMG– Is this the first Minimizer bra ad?] ….Holds the bust high or low and prevents the flesh overriding the corset…. Double Boned Special deep back for Stout and Long Waisted.”

Front view of boned Corslette bust supporter, 1907. The shadow shows where her corset stops.

Elastic back of Corslette Back and Bust Supporter. 1907.

By 1910, a straight, slim silhouette was coming into fashion, and the top of the corset was getting too low to support the breasts.

Lower corsets appeared in this National Cloak Co. ad. February 1910.

Bust confiners to the rescue!

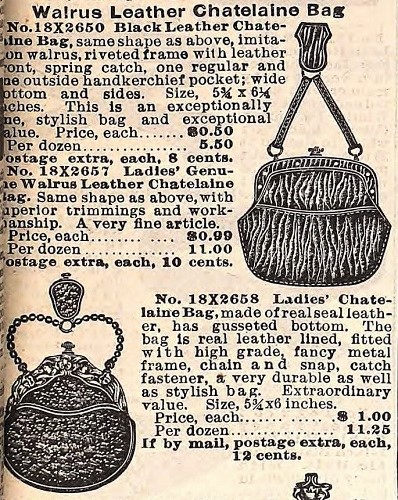

Gossard Bust Confiner ad, Delineator, March 1910.

Detail, Gosssard Bust Confiners, 1910.

Text of Gossard Bust Confiner Ad, 1910.

“The most striking change in the new corsets this season is the lower bust, which to many women will be a grateful improvement. With the low corset, a bust confiner is indispensable to give graceful contour and the desired straight, slender figure….”

Gossard “bust confiner” Style 54 was made to be sewn over the top of the corset, as shown here.

This Gossard Bust Confiner fastens in the front, like a corset cover, with hooks and eyes.

Unlike a corset cover,*** it was heavily boned.

In 1912, the spelling of the new “brassiere” was flexible. Ad for the Siegel-Cooper catalog. Delineator, September 1912.

“Brassiere” is not what a bust-supporting garment was called in France, but American advertisers chose that word to describe this new garment.

Ad for De Bevoise brassieres, “far superior to any corset cover.” June 1910.

The hook at the center front waist of the brassiere attached it to the corset.

In 1912, Paul Poiret was very influential, introducing a long, straight silhouette with a very high waistline and a raised bust. In 1815, women wore a bust-supporting corset under Empire fashions. This photo of a model wearing a high-waisted fashion by Paul Poiret gives an idea of the problem of a corset without bust support. (Her dress and chemise are doing whatever supporting there is.)

One of Poiret’s models, photographed in 1912. Delineator, June 1912. Her breasts seem to be hanging over the top of her corset.

In his book, En Habillant l’Epoque, Poiret told a story about one of his models (not necessarily this one) that has stuck with me for years:

“Am I the only one to know that this bird of paradise concealed the vilest of bodies, … that her breasts, empty and unspeakably awful, had to be rolled up like pancakes in order that they might be packed into her majestic bodice?” — Quoted and translated by Quentin Bell in his book, On Human Finery. [I imagine that Poiret originally said they were rolled like “crepes.”]

OK, the brassiere needed to be invented! But…. The brassieres of 1914 through the early 1920s treated breasts as something which needed to be confined, suppressed, and compressed…. (I wish I could come up with a joke about the monobosom and “solitary confinement.”)

DeBevoise Brassiere ad, May 1914. Delineator.

“The silhouette … for 1914 … is the straight figure, with small hips, large waist, and no bust,” wrote Eleanor Chalmers. Delineator, April 1914, p. 38. (Surprise: this fashion didn’t start in the 1920s.)

1917 fashion illustrations often show a very low bust (a fashion which would be appreciated by some women.)

By 1917, the low bust was an option for chic women.

The natural, uncorseted look meant that breasts could be worn low, although “stout” women were always advised to wear a brassiere.

Famous dancer and fashion icon Irene Castle, an early adopter of bobbed hair, is obviously choosing to go without a brassiere.

Irene Castle’s breasts are not “confined” in this photo from 1917.

Nevertheless, some young women with naturally high busts would choose to wear a breast-flattening brassiere.

Butterick pattern illustrations, September 1917.

It’s hard to believe that young models could achieve a bust this low and flat without a flattening brassiere.

Couture evening dress by Doeuillet, sketched for Delineator, September 1917. Young face; low, flat bust.

That is not a “natural” figure silhouette for a woman.

By 1917, advice was that “With a low corset even a slender woman requires a brassiere or bust confiner.”

Delineator article, Sept. 1917.

This DeBevoise low backed brassiere (like the one in the Delineator illustration above) was recommended under thin evening dresses [probably to prevent nipples from showing.] June 1914, Delineator.

Model brassiere ad, Aug. 1917. From Ladies’ Home Journal.

This “Model” brassiere gives a more natural silhouette (although it implies one wide, single breast rather than a pair.) It has seams over the bust points, so it would flatten the bust somewhat.

A [monobosom] brassiere was recommended for all stout women. It supports the breasts by smashing them and pushing flesh toward the sides. Delineator, February 1917.

Sketch of a couture dress by Paquin, Delineator, December 1917. This model’s bust is oddly low, even though her arms are raised.

1920: This DeBevoise brassiere produces a low curve with no separation between the breasts.

As early as 1920, bust-flattening brassieres and bandeaux, designed for that purpose, were being sold. I was excited to find an ad for the “Flatter-U” brassiere, which I had read about but never seen:

Ad for the Kabo “Flatter-U” brassiere and bust flattener. Delineator, November 1920.

“Especially designed to flatten any unlovely bulge at the diaphragm, bust or shoulders. It really does flatter you, and it makes a flatter you.”

The Flatter-U brassiere, 1920.

This “snugly fitting” bust confiner from 1920 came with a lacy camisole. Kabo Corset Co. ad from Delineator, November 1920.

In the same ad:

Kabo brassiere, ad from November 1920. Delineator.

“…From the slim girlish thirty-two to the full figure of mature lines. It retains the flesh in trim, youthful smoothness….”

[“Youthful smoothness?” How “youthful,” exactly? Age ten?]  It’s 1920 — not yet what we think of as “the Twenties,” but the “boyish” figure is already starting. (“Boyshform” was another punning brand name like “Flatter-U.”)

It’s 1920 — not yet what we think of as “the Twenties,” but the “boyish” figure is already starting. (“Boyshform” was another punning brand name like “Flatter-U.”)

The change didn’t happen overnight. These ads are also from 1920:

Ad for Treo Paraknit Elastic Brassiere. Delineator, February 1920. It’s something like a modern sports bra….

“Model” brassiere ad, Delineator, April 1920. It shows a natural curve but promises “slenderized girlish lines.”

Not all 1922 fashion illustrations show this bust shape, but they were the shape of the future in 1922. Delineator, March 1922.

Long brassiere, from an article in Delineator, February 1924.

Left, a bust-flattening “corselette;” right, a long, flattening bandeau worn with a girdle. Detail from ad for DeBevoise corset company, April 1925.

Buttterick brassiere patterns, Delineator, July 1926. For 36 to 52 inch bust.

Girdle, corselette, and brassiere/bandeau with girdle, Delineator, February 1926.

** Not long after the uplift brassiere became popular in the 1930s, bust padding was reintroduced. (Corset, 1932.) You could buy “Indestructible Breast Forms” in 1939. In 1947, the “push-up” bra was invented by Frederick Mellinger, who started Frederick’s of Hollywood — which is still selling padding to those who think they need it.

*** A corset cover, 1914:

Corset cover, 1914. It is smooth and princess seamed, but it buttons down the front over the corset, so it would have to be very tight to prevent the breasts from popping out over the corset top.

**** By 1926, patents were applied for by at least three “uplift” companies: Model, A.P. (G.M. Poix & Co.) and Maiden Form. (source, Uplift: The Bra in America, by Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau.}

***** This post generalizes based on images from Delineator and Ladies’ Home Journal — just two sources. [Not good scholarship!] For a scholarly history of brassieres in this period (including patented devices) I recommend the well-researched book Uplift: The Bra in America, by Jane Farrell-Beck and Colleen Gau.

NOTE: Most of these images are ones I discovered recently, but some appeared in previous posts. I shared many 1920s’ undergarments in “Brassieres, Bandeaux and Bust Flatteners” (click here), “Underpinning Twenties Fashion: Girdles and Corsets” (click here), “Garters, Flappers & Rolled Stockings” (click here.) And “Corsets and Corselets.” For what happened after the Twenties, see “Changing the Foundations of Fashion, 1929 to 1934.”

Some slim women wore a girdle or corset with a brassiere…

Some slim women wore a girdle or corset with a brassiere…

In the mid-twenties the uplift brassiere was invented, which supported the breasts from the shoulder (with the combination of bra straps and an elastic band below the breasts.)

In the mid-twenties the uplift brassiere was invented, which supported the breasts from the shoulder (with the combination of bra straps and an elastic band below the breasts.)

It’s 1920 — not yet what we think of as “the Twenties,” but the “boyish” figure is already starting. (“Boyshform” was another punning brand name like “Flatter-U.”)

It’s 1920 — not yet what we think of as “the Twenties,” but the “boyish” figure is already starting. (“Boyshform” was another punning brand name like “Flatter-U.”)