Image from Godey’s Magazine, April 1841, found through UCLA’s Digital Image Collection. Casey Fashion Plates rbc2847

UCLA Library Digital Image Collection: Online Collections Related to Fashion and Costume

While following up recommendations for online Museum collections, I accidentally discovered this wonderful site, which I have barely begun to explore. It acts as a portal to many online collections and research materials. The entire UCLA Library Digital Image Collection must be huge (click here to see the Fashion home page), since there are dozens of sites (with descriptions and live links) related to just the site for Fashion and Costume (click here). For a list of accessible fashion magazines and newspapers, click here. Below you’ll find just a small selection of the extraordinary collections you can find through the Digital Image Collection.

Casey’s Fashion Plates

The image at the top of this page is from the collection of Casey’s Fashion Plates at the Los Angeles County Library — over 6200 images of hand-colored fashion plates. (Click here.)

“The Joseph E. Casey Fashion Plate Collection at the Los Angeles Public Library contains over 6,200 handcolored fashion plates from British and American [and other] magazines dating from the 1790s to the 1880s. All of the plates are indexed and digitized for online viewing.” It includes thousands of dated images from early 1800’s sources, including Ackerman’s Repository, Godey’s Magazine, Ladies’ Museum, Ladies’ Magazine, La Belle Assemblee, Petit Courrier des Dames, and many, many more.

This digitized collection is really user-friendly, grouping the plates by date instead of by source. (You could search by magazine name if you wanted to.) You can search by date, too. Type in a year and pages and pages of plates appear. I chose 1815; this is one of many images that I found. (Let’s pretend it’s Jane Austen and her sister, Cassandra.)

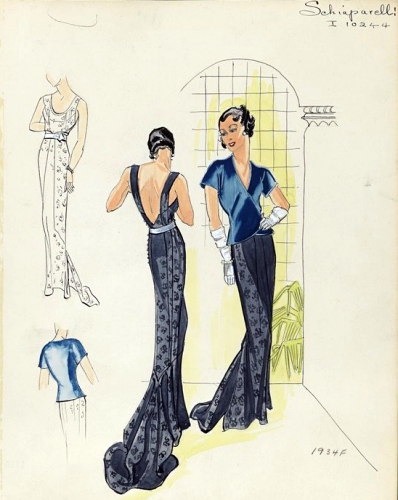

Brooklyn Museum’s Henri Bendel Fashion and Costume Sketch Collection

Another wonderful collection accessible through the UCLA site is the Henri Bendel Fashion and Costume Sketch Collection 1912 to 1950. (924 images are online at present) This archive is in the possession of the Brooklyn Museum, but you don’t have to go to Brooklyn to see hundreds of sketches of dresses (and even bathing suits), including many designer names. (Click Here.)

It’s also well-thought out: when your mouse hovers over the thumbnail image, a description and date appears. Click to get a larger view and more data. There are over 11,000 sketches in the Bendel Collection, but most of the 924 that are online are for the era 1912 to early 1920s. (They are gorgeous, and most are in color! If you are a fan of styles from the Titanic era and the first years of Downton Abbey, prepare to spend hours here.) I saw designs attributed to Doucet, Worth, Callot Soeurs, Lanvin, Premet, and many other “name designers.” Among the few sketches from the 1930’s that have been put online was this evening gown by Schiaparelli:

Bonnie Cashin Collection of Fashion, Theater, and Film Costume Design

“The collection contains Bonnie Cashin’s personal archive documenting her design career. The collection includes Cashin’s design illustrations, writings on design, contractual paperwork, photographs of her clothing designs, and press materials including press releases and editorial coverage of her work.”

Lovers of Bonnie Cashin designs will enjoy the photos and design sketches of many of her classic coats, knits, etc. (Click here.) The images are under copyright, but you can see a sample sketch for a characteristic tweed coat by clicking here. If you searched a little longer, you could probably find a photo documenting the finished coat. This is a huge archive.

You can also see more about Bonnie Cashin at the next online collection I’ve chosen from UCLA’s Digital Image Collection:

The Drexel Digital Museum Project Historic Costume Collection

The collection is searchable, (and images are under copyright) but this link will take you to the Galleries page — which includes slide shows of Bonnie Cashin clothes and Villager Sportswear textiles! Click here.

“The Drexel Digital Museum Project: Historic Costume Collection (digimuse) is a searchable image database comprised of selected fashion from the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection (FHCC), designs loaned to the project by private collectors for inclusion on the website, fashion exhibitions curated by Drexel faculty and fashion research by faculty and students. To best present and create access to this online resource, the image standards of the Museums and the Online Archive of California initiative and the metadata harvesting protocols of the Open Archive Initiative have been implemented to insure sustainability, extensibility and portability of the digimuse digital archive.” —

A World of Riches, Digitized

I will add some of these links to my sidebar of “Sites with Great Information,” so they will be easy to locate in the future. But first, I’m going take a coffee break and read a copy of the French Vogue, February 1921 (click here) thanks to the UCLA Library’s Digital Image Collection!