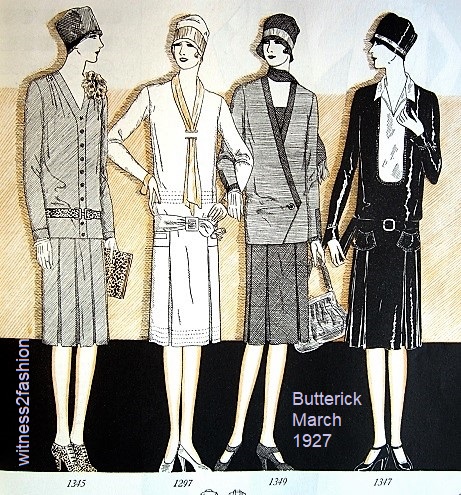

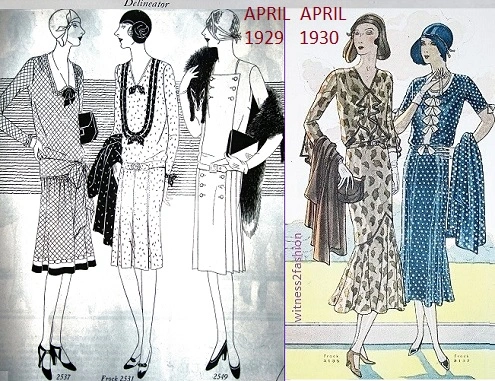

Only one year separates these Butterick patterns from Delineator magazine. This is rapid fashion change.

The change in fashion that took place between Fall of 1929 and Spring, 1930 — just a few months — fascinates me. The fact that a completely different fashion silhouette was adopted during a time of economic crisis — when pennies were being pinched — makes it even more astonishing.

Just to get our eyes adjusted and refresh our memories of 1929 before the change, here are several images of couture and of mainstream Butterick sewing pattern illustrations from July 1929.

French couture sportswear, illustrated by Leslie Saalburg in Delineator, July 1929. Short and un-fussy.

These fashions are unmistakably late 1920s. Note the hem length, which just covers the knees. There is a crisp, geometric quality about many of these outfits.

Couture sportswear illustrated by Leslie Saalburg for Delineator, July 1929.

Patterns for home use:

Spectator sportswear; Butterick patterns illustrated in Delineator, July 1929. The dress at left is soft and flared, a hint of things to come. The dress at right is crisply geometric. Both are short.

1920’s day dresses, Butterick patterns 2697 and 2707. Delineator, July 1929. Mostly straight lines.

Butterick patterns for sportswear, Delineator, July 1929. Simple, pleated, short.

Whether we look at French couture or home sewing patterns, the silhouette and the length are definitely “Twenties.”

In the 1929 Fall collections, couturier Jean Patou showed longer skirts — well below the knee — and took credit for changing fashion from the characteristic Twenties’ silhouette to the longer, softer, Thirties’ look. (A few other couturiers also showed longer dresses, but he took the credit for being first.)

French couture fashions sketched for Delineator, November 1929. The large illustration at left is an ensemble by Patou — noticeably longer than the other designers’ hems.

“Paris revolutionizes winter styles.” Compare the hem on the dress by Patou, second from left, with those from Molyneux (left, very “Twenties”) Cheruit (third from left,) and Nowitzky (also “Twenties” in spirit, far right.)

Below is the Fall 1929 version of Chanel’s famous black dress. (In the original, from 1926, hems had not reached their shortest length.)

This variation on Chanel’s famous little black dress — with a slightly different placement of tucks –falls just below the knees in 1929, the season when Patou was pioneering longer dresses.

By Fall of 1929, Chanel’s “little black dress” (a sensation in 1926) is just below the knee. It also has a natural waist.

You may have noticed that waistlines are rising as hems are falling; that’s a topic deserving an entire post, but….

Delineator, October 1929, p. 25. “Higher Waists, Longer Skirts.”

The flared dress at left has a softer, less geometric look, and shirring near the natural waist instead of a horizontal hip line. Delineator, October 1929. This dress seems to be “in the stores” rather than a Butterick pattern.

Between July couture showings and October, 1929: That is how fast commercial manufacturers picked up on the new trend for longer skirts and natural waistlines.

Butterick patterns in Delineator, October 1929.

Delineator (i.e.,Butterick Publishing Co.) had offices in Paris where the latest couture collections were sketched (and copied.) In this case, longer skirts appeared on patterns for sale very quickly. (The process of issuing a pattern took several weeks, and the magazine had a lead time of a month or so, as well.)

When these patterns appeared in April, 1930, nothing was said about their length. Old news!

Dresses for women, up to size 48. Butterick patterns from Delineator, April 1930, p. 31. From left, “tiny sleevelet,” “flared sleeves,” “white neckline,” and “short kimono sleeves.”

By April 1930, what was notable about these dresses, to the editors of Delineator, was the variety of their sleeves!

Back views of Butterick 3143, 3179, 3173, and 3180. Delineator, April 1930, p. 31.

Longer styles had been in the news for several months.

Butterick patterns from Delineator magazine, January 1930.

Butterick patterns from Delineator, February 1930. Hems have fallen. Waists are in transition.

The most interesting article I found about this change from “Twenties” to “Thirties” was in Good Housekeeping magazine, November 1929, pp. 66 and following.

In “Smart Essentials of the Winter Clothes,” fashion editor Helen Koues wrote:

“They differ from any we have had since the war…. To be sure, last season Patou and a few houses tentatively raised the waistline, and we talked about it and made predictions. But now the normal or above normal waistline is here, and anything remotely resembling a low waist is gone. We have had it a long time, that low waist and short skirt, and it is only fitting and logical that it should make way for some sort of revival. [“Directoire, Victorian, Princess….”] We have worn high waists and long skirts before — both higher and longer. But coming with a greater degree of suddenness than any change of line has come for some years, it is an inconvenient fashion. What are we going to do with our old clothes? [My emphasis.]

“The new silhouette will be taken up just as fast as the average woman can afford to discard her old wardrobe…. The average woman will replace what she needs to replace with new lines, but she will take longer, because she will wear out at least some of her old clothes. In three months, however, all over America the tightly fitted gown, the longer skirt, the high waist will have superseded the loose hiplines of another season. and the main reason for the speed of this change is that we are ready for it. We are bored with the old silhouette, for we have had it too long — so long, in fact, that… we were beginning to think that we would wear short skirts and low waists till we die…. The psychological moment has come….

“Skirt lengths are particularly interesting: for sports, three inches below the knee is the right length; for street clothes, four inches below, and for the formal afternoon gown about five inches above the anklebone. Evening, of course, right down to the ground… and probably with as much length in front as back…. These are the average lengths.

“Skirts are slimmer than ever, if that is possible, or at least the effect is slimmer, because with the added length the flare necessarily begins lower down. But the flare is still there in full force….”

Colors for Spring, 1930. Butterick patterns in Delineator, March 1930. Flares, softness, and a coat that is shorter than the dress.

Koues also noted that the new three-quarter coat, “that strikes the gown just above the knee” was in style, although she did not mention that this, at least, was a break for women who could afford a new dress but not a new winter coat. Koues recommended wearing longer knickers (underwear) in winter to make up for the shorter coat.

Short coats or long jackets, February 1930, Delineator.

Vogue, October 26, 1929 reminded readers “We told you so!”

If you have access to Vogue magazine archives you may enjoy a timeline of Vogue fashion predictions from October 26, 1929. It began, “We told you so! If you are one of the many women who are complaining that the new mode means a completely new wardrobe, that you were caught unawares, we take no responsibility. For two whole years, we have been reiterating and reiterating a warning of the change to come.”

Here are some highlights of Vogue‘s predictions:

JANUARY 1, 1928: “The Waist-Line Rises as the Skirt Descends…”

JANUARY 13, 1928: “Skirts ….. Will Be Longer” — “Waist-Lines Will Be Higher” — “Drapery and the Flare Will Be Much in Evidence.”

APRIL 13, 1929: “What looked young last year looks old this season — all because longer, fuller skirts and higher waist-lines have been used so perfectly that they look right, smart, and becoming.”

JUNE 22, 1929: “The hemline is travelling and so is the waistline. One is going up, and the other is coming down.”

Vogue ended, “Need we say more? Surely, Vogue readers are well prepared.”

This is what designers in Paris were showing in Spring, 1930.

Paris Couture, sketched for Delineator, May 1930. Every one has a long skirt and a natural waist.

I began with several images of patterns and couture from July 1929. Here are some dresses from July 1930, showing how completely the Twenties’ look had been “superseded” by the Thirties — in one year.

The Twenties are over. The Thirties are here. Patterns from Delineator, July 1930.

Naturally, in 1929-1930 some women thought the new long skirts made them look “old” while some thought they looked “youthful;” but that is a story for another day!