A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the popularity of striped coats in 1924.

This week I found this photo in Alison Lurie’s book The Language of Clothes, illustrated with images assembled by Doris Palca.

A British fashion photograph of motoring and sports coats, 1924, from The Language of Clothes, by Alison Lurie.

The Language of Clothes, by Alison Lurie, 1981

I was de-accessioning my library, and had listed this book on Amazon, but I didn’t have to read more than a few sentences to realize that I want to read it again. Lurie’s observations about fashion are perceptive, very well-written and often very amusing. Her comment on these coats is:

“Women entered the second decade of the twentieth century shaped like hourglasses and came out of it shaped like rolls of carpet.”

When I was teaching, I always stressed that “Costume communicates.” We all speak the language of clothes, and we constantly make judgements based on our reading of what other people wear. Lurie’s book is about the subtle statements and psychological impulses behind our clothing choices, with chapters on “Clothing as a Sign System,” “Youth and Age,” Fashion and Status,” “Fashion and Sex,” and many other topics that explore the clothes we usually take for granted. Her comments on the fashions of the 1920s, in the chapter “Fashion and Time,” interested me particularly, because I have been thinking many of the same thoughts while looking through pattern illustrations of the twenties — but Lurie anticipated my ideas by thirty years.

And she writes really well, so that there is a lot of information packed into her seemingly effortless prose.

Dressing as Children: Thoughts on 1920s Styles

After summarizing several theories about why women minimized their breasts and hips in the twenties, Lurie reminds us that . . .

“It has been sugested that women were asserting their new-won rights by dressing like men; or, alternatively, that they were trying to replace the young males who had died in World War I.

“…But a glance at contemporary photographs and films shows that women in the 1920s did not look like men, but rather like children — the little girls they had been ten to twenty years earlier….

“…And although [the flapper] might have the figure of an adolescent boy, her face was that of a small child: round and soft, with a turned-up nose, saucer eyes, and a “bee-stung” mouth.

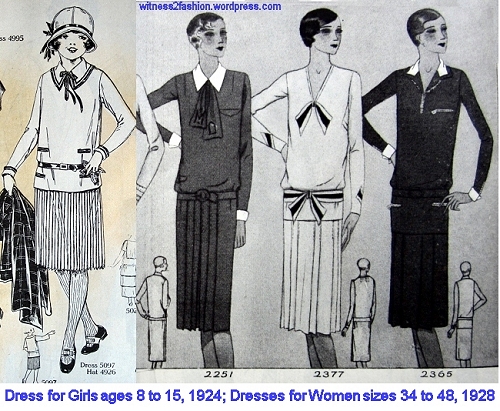

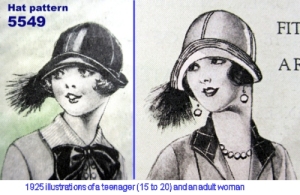

I have been noticing that patterns for young women, aged 15 to 20 — i.e., ‘flappers’ — were illustrated with very round-headed, big-eyed, baby-like heads, like the prototypical flapper cartoon character, Betty Boop.

Illustrations of a teenager and an adult woman wearing hats made from the same pattern, 1925. Delineator magazine.

Very large eyes, spaced far apart, in a round — rather than oval — head, with a tiny nose and “rosebud lips;” those are the traits associated with an infant’s head.

Alison Lurie goes on to say, “One popular style of the 1920s was the dress cut to look like a shirt, with an outsize collar and floppy bow tie of the kind seen on little boys ten or twenty years earlier. [See above, left.] Another favorite was the Peter Pan collar, named after [the boy who] . . . was chiefly famous for his refusal to grow up. . . . Middy blouses and skirts were now worn by grown women as well as children, and the ankle-strap button shoes or “Mary Janes” once traditional for little girls became, with the addition of a Cuban heel, the classic female style of the twenties.”

“I Won’t Grow Up”

My own observation is that dresses considered suitable for little girls aged 8 to 15 (or younger) in the early 1920s became the adult fashions of the later 1920s. When adult women were still wearing mid-calf-length skirts, in 1924, 12-year-old girls were wearing skirts that came just to the knee. Two years later, adult women — not just ‘flappers’ — were wearing knee-length skirts. The curves of a sexually mature female body were suppressed, or at least de-emphasized. The ideal may have been a ‘boyish’ figure, but it was also the figure of a little girl, too young for adult responsibilities, but insisting upon adult freedom of behavior.

Earlier in the century, young women looked forward to the day when they could “put up” their hair and let down their hems. By 1925, women were reverting to schoolgirl clothing styles: dropped waist lines, short skirts, pullover dresses, and middy-type blouses worn outside their skirts rather than tucked in (a look previously only seen on gym suits and children’s outfits.) Here’s another example of a child’s dress influencing the adult dress on the right:

At least, The Language of Clothes got me thinking more deeply about fashion trends. I’m looking forward to reading it straight through– but it’s hard not to skip ahead to such enticing topics as “Sexual Signals: The Old Handbag,” and the underlying meanings of “Color and Pattern.” It’s available in used hardcover for about $10 plus shipping.