The Van Raalte Company is probably better known today for its gloves, stockings, and underwear, but hat veiling was one of its first products. In 1915, Zealie Van Raalte applied for a patent on his special hat veil which had an opening for the crown of the hat, and “which can be readily and quickly secured to the hat with the least possible delay and trouble in securing the correct adjustment, and which is detachable or removable at all times.” Dollhouse Bettie has written a fine series of illustrated articles on the history of the company. Click Here.

“A Veil Makes a Plain Face Pretty…”

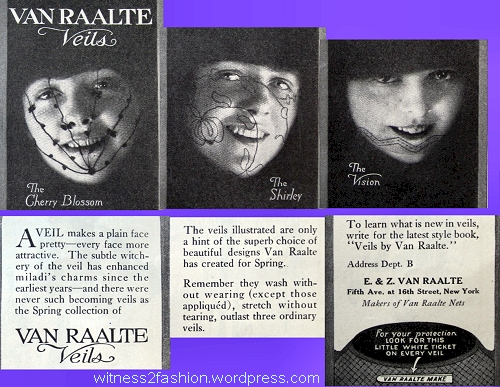

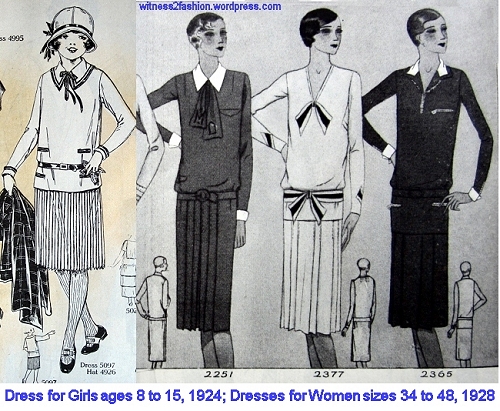

“A veil makes a plain face pretty — every face more attractive. The subtle witchery of the veil has enhanced miladi’s charms since the earliest years — and there were never such becoming veils as the Spring collection of Van Raalte Veils.” According to Dollhouse Bettie, the first Van Raalte plant opened in 1917, so this is a very early advertisement, one of a series that ran in Butterick’s Delineator magazine that year. “The Cherry Blossom” and “The Shirley” veils are shown drawn tightly over the face. (“The Vision” seems to stop above the chin and gives me the impression of a tribal tattoo!) Perhaps not coincidentally, hats with veils appeared on some of the pattern ilustrations in the same issue:

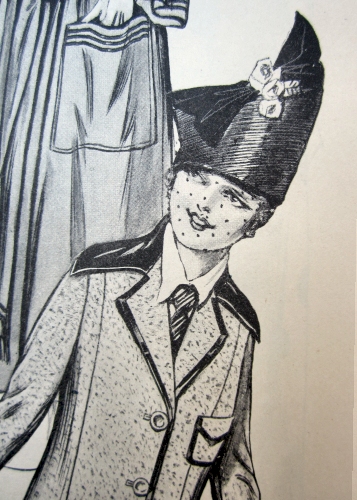

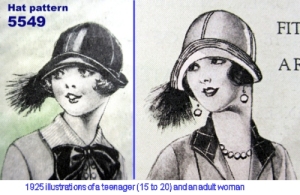

Two of these illustrations seem to show the same hat, which has a veil similar, but not identical to, Van Raalte’s “Shirley.”

I often see the same hat used repeatedly over several months in Delineator pattern illustrations. Apparently the illustrators worked from live models who were accessorized from a stock of hats, purses, boas, etc.

The “Winsome” Veil

“A white veil makes the fairest face seem fairer — and gives a fashionable touch to the Spring or Summer costume. [Suntans were not yet in fashion in 1917.] Since this veil slips over the hat and exposes the crown, it may be one of Van Raalte’s patented veils, or it may be tied behind the hat. Note the model’s lips — lip rouge was becoming acceptable on ‘nice’ women.

I love the way the handbag echoes the colors of the jewels on the hat. [The hat does not have a brown feather — that is part of the fur worn by an adjacent model.]

Long Veils

A veil this long was versatile and could be tied in place behind the hat, and (if the hat was not too big) even used to secure the hat on windy days. Riding in carriages or the open cars of 1917 often required something stronger than a hatpin to keep your hat from blowing off. [Henry Ford refused to make a ‘closed car’ until 1927, when the Model A was introduced to compete with the more comfortable cars being produced by his competitors.]

Van Raalte Veils could be identified by their small paper label: