I finally got my hands on a copy of Linda Przybyszewski’s The Lost Art of Dress (after reading several very favorable reviews, including this one from The Vintage Traveler). I had barely started reading the book when I found a paragraph on page 4 about the importance of home economists to the war effort in World War I:

“With the help of the home economists, the US Food Administration recruited some 750,000 women to help teach the rest of America’s women about food conservation . . . . The recruits got a pin, a badge, and a pattern for an apron. The white apron was named after Herbert Hoover, who was then head of the Food Adminstration. The Hoover apron’s claim to design fame was that it completely wrapped around your dress and protected it from spills, opening in the front with a large overlap. . . .”

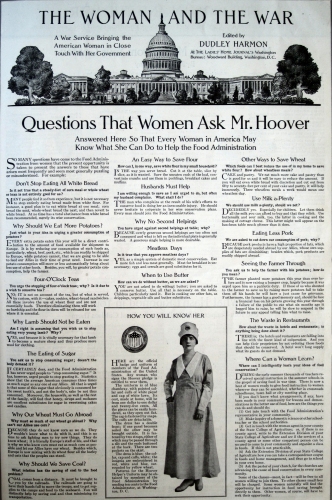

“I’ve seen one of those,” I thought. And here it is, from Ladies’ Home Journal, September, 1917.

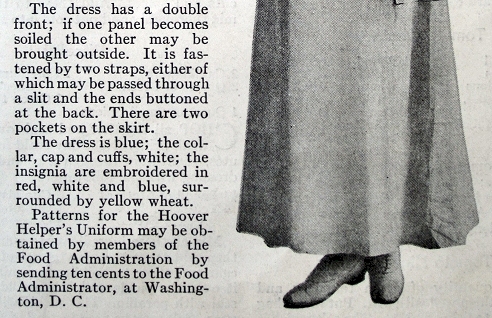

The Official Badge and Uniform of Members of the Food Administration of the United States, WW I. From an official article in Ladies’ Home Journal, Sept. 1917.

“. . . .Since it could overlap in either direction, you could wear it twice as long as a regular apron before it was too filthy to wear. It was practical, and sort of disgusting, but it became a popular design. Renamed “Hooverettes” or “bungalow aprons,” done up in perky prints with ruffles at the neck and sleeves, they were sold in stores as dresses over the next two decades.” — Linda Przybyszewski, The Lost Art of Dress, p. 4.

Przybyszewski cites an article by Joan Sullivan from Dress 26, “In Pursuit of Legitimacy: Home Economists and the Hoover Apron in World War I,” which I have not read. It’s available from The Costume Society of America.

I’ll print the picture of the uniform again, in two sections, so the text and details will be more legible:

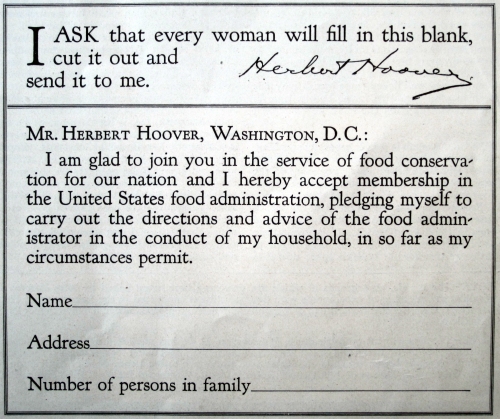

In spite of Dr. Przybyszewski’s description, the official apron was not white, but “of blue chambray.” The fact that the pieces all “open out flat” for ironing must have been a great point in its favor, like the removeable cuffs. Notice that “any woman who signs the Hoover pledge is entitled to wear” this uniform. The Hoover Pledge appeared in the August Ladies’ Home Journal and other women’s magazines.

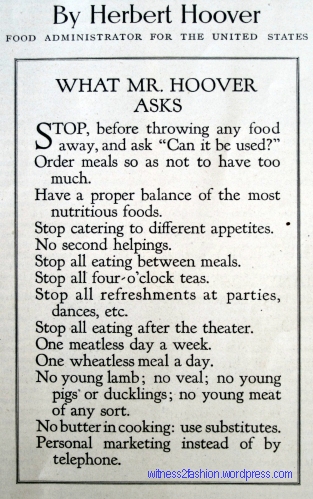

In spite of Dr. Przybyszewski’s description, the official apron was not white, but “of blue chambray.” The fact that the pieces all “open out flat” for ironing must have been a great point in its favor, like the removeable cuffs. Notice that “any woman who signs the Hoover pledge is entitled to wear” this uniform. The Hoover Pledge appeared in the August Ladies’ Home Journal and other women’s magazines.  Here are the rules these women were agreeing to follow:

Here are the rules these women were agreeing to follow:

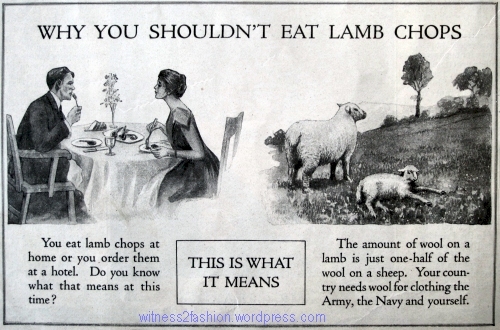

Wartime illustrations explaining the food conservation rules appeared throughout the Ladies’ Home Journal. Aug. 1917 .

American women had been reading about the sacrifices made by European women during the twenty months that passed before the United States entered the war. The women’s magazines showed pictures of women in uniform in England, of women filling previously male occupations, and American women were eager to do their part. Judging from the fashion illustrations and patterns available, they were also depressingly eager to wear uniforms, or clothing that looked like uniforms, as if one couldn’t volunteer to host a war relief fund-raiser until dressed like a pseudo soldier.

Aprons and House Dresses

It’s a little surprising to modern eyes to see this all-covering, sleeved garment described as an apron, but the distinction between aprons and house dresses remained blurry into the 1920s. The “Hoover apron” was very similar to these 1917 house dresses from Butterick — dresses which preceded the Food Administration uniform:

Butterick patterns, January 1917. From left, a negligee, a house dress, a wrap house dress, and a negligee. From Delineator magazine.

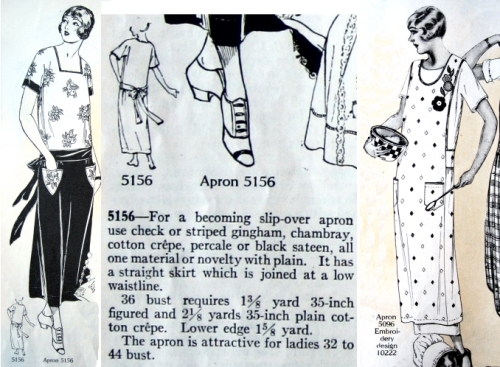

However, in the 1920s, aprons that we would call dresses, and which pulled on over the head, appeared equally with sleeveless aprons that primarily covered the front of the body.

[For those who do not remember the house dress, it was a dress — often with pockets — that was easy to launder and was worn while doing housework. Even in the 1940s, no woman with pretensions to the middle class would wear a house dress outside her own yard. In 1917, they were also called “porch dresses.”]

The floral garment in the center is described as an apron. The wrap dress on the right is a “house dress.” Perhaps some women would have called them Hooverettes?

Thanks especially for that clear explanation of “apron” and “house dress.” It can be very confusing! Wouldn’t it have been much more practical if those big cuffs weren’t white?

The popular Swirl wrap house dress was originally described as an apron, and that was in 1940.

My mother the nurse always claimed that the white accessories were a diabolical plot by the hospital admins. to keep the nurses busy! Actually, I think it had something to do with the appearance of hygiene.

Pingback: More About Wrap Dresses | witness2fashion

Pingback: American Red Cross Service Uniforms, 1917 | witness2fashion

Pingback: “Original and Becoming” Work Clothes, 1917 | witness2fashion

Pingback: McCall Fashions for January 1918 | PatternVault

Pingback: “Service Suits” for Girls, Boys, and Women in 1917 | witness2fashion

Pingback: Wrap-look Dresses from June, 1931 | witness2fashion