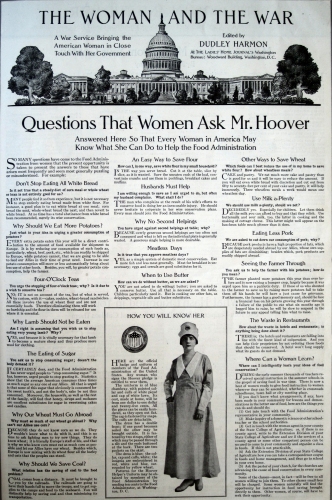

After the U.S. declared war in April of 1917, there was a great outpouring of volunteerism. Women were eager to support “our boys,” and magazines aimed at female readers were a perfect, pre-existing medium for the government to communicate with millions of households all over the country. Official articles like the ones quoted here appeared in both Butterick’s Delineator and Ladies’ Home Journal, among others.

Women Wanted to Wear Uniforms, Too

So many women wanted to wear some type of official uniform while doing “war work” that cautions were repeatedly issued.

Official Red Cross policy statement by William Taft, Chair of Central Committee, August 1917 issue of Ladies Home Journal.

The new, authorized Red Cross Corps uniforms (pictured above) were described in September, but the problem of unauthorized used arose again in October:

Clearly, there were unscrupulous people “raising money for the Red Cross” but not turning over all the proceeds to the charity. “Red Cross Bazaars” had to have prior approval at the local level or use of the name was not permitted. And only members of the Red Cross who had taken a loyalty oath and met other requirements could wear Red Cross uniforms.

There was a difference between being a Corps Member and being a Red Cross Nurse — only women who had completed two years of nursing training, who had an additional two years practical nursing experience, and who were registered nurses in their own state could apply to be a Red Cross Nurse. However, there were many other vital ways for a woman to serve through the Red Cross. Wearing any of these Corps uniforms required a permit.

American Red Cross Supply Corps Uniform & Clerical Corps Uniform, 1917

Supply Corps Uniform

“In this division of Red Cross Work the service of the members is to prepare surgical dressings, hospital garments and all other Red Cross supplies. The uniform is a white dress, or a white waist [i.e., blouse] and skirt, with dark blue veil and white shoes. Small Red Cross emblems are worn on the veil and on the left front of the dress. The arm band is dark blue, with a horn of plenty embroidered in white.” [Her scalloped collar gives the impression that she is wearing white clothing she already owned with the uniform head covering and armband.]

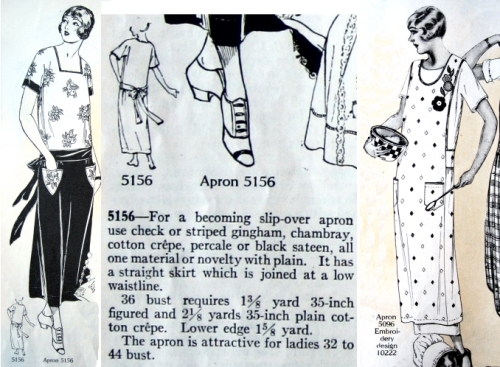

Women who wondered why they had to wear a head covering while making bandages and dressings were reminded that this was necessary “for sanitary reasons;” “she must also wear an apron for the same purpose.”

The Demand for Bandages: “The Red Cross could send all its available supply to Europe for instant use there and start all over again. . . .Wounded soldiers in France to-day are being bandaged with straw and old newspapers.” — William Howard Taft in Ladies’ Home Journal, August, 1917.

The official Red Cross patterns for making pajamas, surgeon’s gowns, etc., were available from pattern companies, stores, or Red Cross Chapters for 10 cents each.

Clerical Corps Uniform

“This service is designed to include the women who do the large amount of clerical work in an active Red Cross Chapter — the volunteer stenographers, bookkeepers, etc. The uniform consists of a one-piece gray chambray dress, a white, broad collar, white duck hat with yellow band, and white shoes. The Red Cross emblem is worn on the hat and on the left front of the dress, while the arm band is yellow, with two crossed quill pens embroidered in white.”

By October, the national headquarters of the American Red Cross was receiving 15,000 letters per day. To cope, it was decentralized, with thirteen divisions spread to large cities throughout the U.S. When you consider that women all over the country were being asked to roll bandages, to make hospital garments and supplies such as sheets and pillowcases, to knit warm scarves, sweaters and socks for servicemen, and to supply 200,000,000 “comfort kits” for soldiers, you can imagine the logistical nightmare of shipping and sorting that had to be done by the Supply Corps and the Clerical Corps. Shipping companies agreed to deliver packages addressed to the thirteen Red Cross collecting centers for two thirds the usual price, but all shipments from local Red Cross chapters had to have separate notices of shipment mailed, as well.

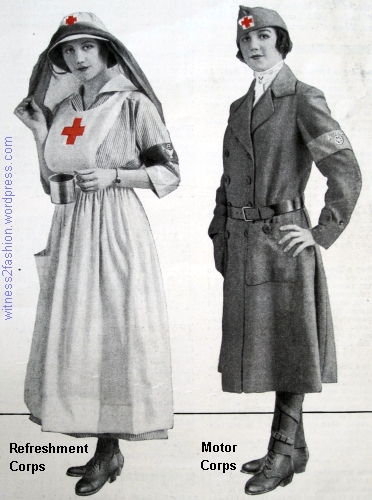

American Red Cross Refreshment Corps and Motor Corps Uniforms, 1917

Refreshment Corps Uniform

“The Corps feeds soldiers passing in troop movement or en route to a hospital, or furnishes lunches in the way of extras to troops in near-by camps. The uniform is a dark blue and white striped chambray dress, long white apron with bib, white duck helmet with dark blue veiling, and tan shoes. The arm band is dark blue, with a cup embroidered in white. A large Red Cross emblem is worn on the apron bib and a small one on the helmet.”

Presumably because of the dangers of fraternization, “no person under 23 years of age may be a member of the Refreshment Corps.” Also, because attempts had been made “to injure our soldiers through tampering with Red Cross articles,” all foodstuffs had to be prepared in supervised kitchens and “by persons whose devotion to the United States can be vouched for.” (Taft, October 1917.)

Motor Corps Uniform

“All women volunteer drivers for Chapter work are included in this service. Members may or may not furnish their own cars. The uniform is a long gray cloth coat with a tan leather belt, a close-fitting hat of the same material, riding breeches, tan puttees or canvas leggings and tan shoes. The Red Cross emblem is worn on the hat. The arm band is light green embroidered in white.”

Although her riding breeches are modestly covered by the length of the coat, this is a variation on a male chauffeur’s uniform. Most cars were open (and cold) in 1917. Whether or not you supplied your own vehicle for transporting troops, this uniform had to be purchased, not home-made. It cost about $25.

Who Can Wear These Red Cross Uniforms?

American Red Cross Nurses Uniforms

Alessandra Kelley, who writes the blog Confessions of a Postmodern Pre-Raphaelite, found a 1918 copy of The Red Cross Magazine with pictures and descriptions of the official uniforms for Red Cross nurses at home and serving overseas. She kindly photographed it in detail for the use of historians and re-enactors. Click here for a link to her great post about Nurses Uniforms.

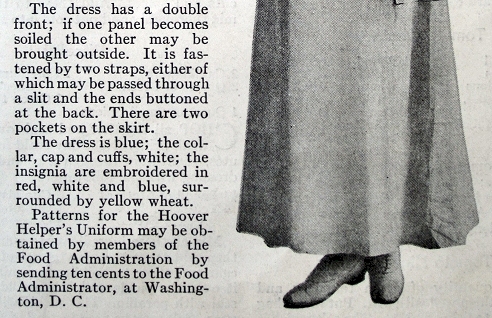

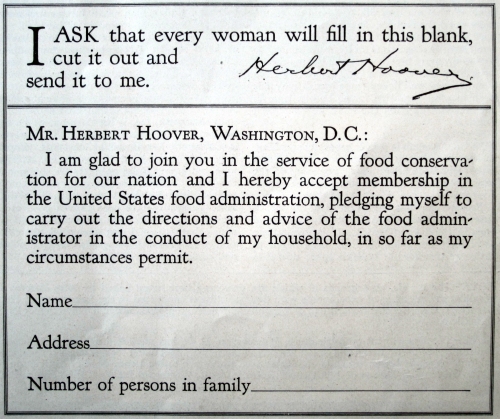

I have also written about the U.S. Food Administration Uniform, 1917.