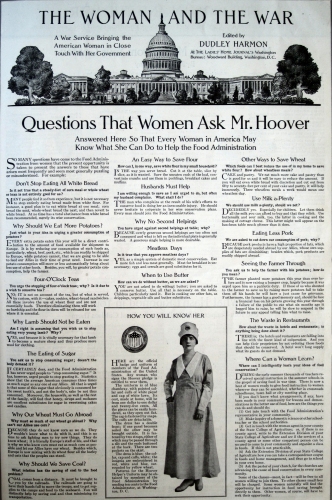

As often happens, a comment on one post — about the Official Uniform of the Food Administration in 1917 — led me to some new information. The Vintage Traveler mentioned the “Swirl” dress of the 1940s, which was also a wrap dress, perhaps a direct descendant of the “Hooverette” wrapped apron dress. According to Fuzzie Lizzie, the Swirl dress dates back to 1944. Visit her fascinating and well-illustrated article by clicking here.

That reminded me of other wrap dress patterns — more like house dresses than the “uptown” Diane von Furstenberg knitted jersey dresses that were ubiquitous in the seventies and are still with us today. There’s no doubt that the wrap dress, which preceded the Herbert Hoover wrapped apron dress, is a style with longevity!

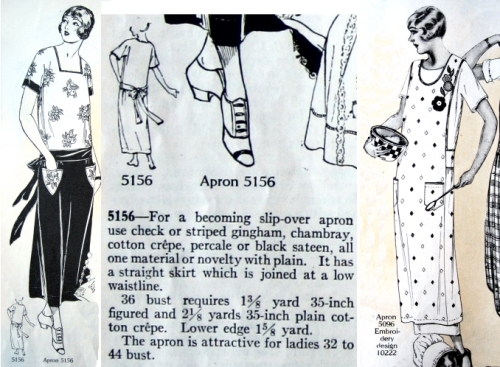

This wrap-around apron from 1917 closes with buttons, rather than ties. So does the 1952 version below.

Butterick B4790 Retro 1952 Pattern

This wrap dress, like the “swirl” dresses that preceded it, looks ready to wear out of the house. It has a button fastening, rather than a tie. It’s a long way from the Ethel Mertz look. [Vivian Vance, who played Ethel, was contractually required to look more dowdy than Lucille Ball.] A copy of a 1952 Butterick pattern, the envelope shows the dress open and laid out flat.

It looks like the wearer of this wrap dress would be well covered, avoiding a very embarrassing — and ass baring — experience I had with a 1960s back wrap skirt, which blew open while I was walking down a busy commercial street. I didn’t realize what was happening until cars started honking at me. Lesson learned: never wear a wrap dress that doesn’t wrap all the way to the side on the underlap!

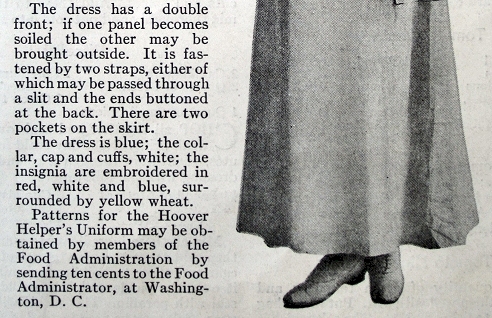

Simplicity Pattern #5449, dated 1964

To me, the bias binding on dresses like this one put them more in the “apron” family than in the housedress family. I have strong memories of bias bound dresses at the local dime store. They were usually made of very cheap fabric, heavily sized, and they turned limp and cheap-looking after their first washing. However, Simplicity # 5449 could be made of a good quality cotton fabric, and the envelope says that the “dress front laps to back fastening with tie ends,” so it would cover the wearer completely, fore and aft, even in a high wind.

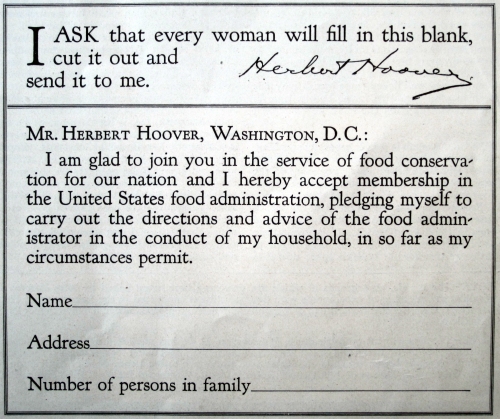

Simplicity Pattern #8278, dated 1969

This wrap dress from 1969 couldn’t possibly be mistaken for an apron or a housedress. It can also be made as a tunic and worn over flared trousers. But that’s the only way I would have worn it, because the back of the pattern shows that the front pieces are symmetrical.

When you sit down, this kind of wrap dress pulls open and exposes your knees and usually some underwear. Of course, a good dressmaker could alter the pattern and extend the skirt underlap to the side seam, and tie or button it in place, but I didn’t have that kind of patience or expertise in 1969.