This article suggests seven different work outfits suitable for American women in wartime. One of them, surprisingly, is a dress with a divided skirt — what would later be called a culotte skirt. Sadly, although the Ladies’ Home Journal sold its own mail order patterns, none of these outfits has a pattern number. The article is “editorial,” suggesting that outfits which would have been rather shocking a few months earlier may now be “safely” worn on the streets and in the stores of an America at war. I’ll show an overview first, and then describe each outfit with its accompanying text. Except where noted, all illustrations are from the same Ladies’ Home Journal article, dated September 1917.

Women in Trousers, 1917

Women were already wearing bloomers for gym classes and jodhpurs or riding breeches when on horseback. In July of 1917, a rival fashion magazine, Delineator, had suggested that a sort of trouser outfit might be worn for housework:

Butterick pattern No. 9294 for a smock dress over bloomers. House-dress No. 9288 is on the right. Delineator, July 1917.

“For the home-reserve corps comes this new costume (design 9294) suited to the woman who wants to go on active service — either at home, out camping, or for gardening.” The house-dress next to it shows a typical hem length for women. As skirts became shorter, they were usually worn with opaque stockings or boots.

The bloomer outfit above, with gathered cuffs, is a close relative of women’s pajamas like these, also from 1917 :

The Ladies’ Home Journal Suggests Some Trouser Outfits for 1917

“Even the most inveterate feminine ‘slacker’ will be lured into laborious occupations if such fascinating uniforms as these are to be worn.” [After World War I began in August, 1914, women in Europe began filling traditionally male occupations in order to free men for military service. “Land girls” worked on farms; women became train and street car conductors, munitions workers, heavy equipment operators, etc.]

“[These] trig knee-buttoned trousers …, worn with a laced skirted blouse, tam and laced high boots, were designed for an ardent motorist. Surely even the most stubborn opposition could be overcome at sight of these!” For an official Red Cross Motor Corps Woman’s Uniform, click here.

“It may be that the fair farm maid . . . has paused dissatisfied with her work, but surely no doubt could lurk in her mind as to the fitness of her well-made olive-drab khaki suit. Side fullness given by plaits [pleats] begins at the underarm and ends at the hem.”

“[Above] One may rake, pile, and burn autumn leaves in the serene consciousness that no flickering flame will catch on the strapped leggings worn with [this] pocketed bloomer suit. . . .”

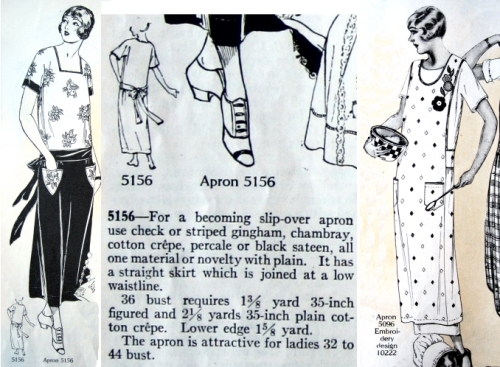

“Indoors expediency demands simplified dressing, and the adoption of such an attractive combination — apron, blouse, divided skirt — as shown above . . . made of ticking, may do much to encourage women to take up their housework seriously.” [Note the unusual “divided skirt!” In 1917, the word apron could refer to a garment we would now call a dress.]

“When marketing is part of the day’s routine, a long tucked smock of khaki with wide-bottom trousers… makes a work outfit one could safely venture out in.” [Think about what is implied by “safely.” The government encouraged women to collect their own groceries rather than having them delivered, freeing the deliverymen for active service.]

“Strapped leggings, a high buttoned collar, hip pockets and wrist straps effectively suppress any loophole which may hint of feminine softness in [this] public service uniform.” Oh, really ? Her pose makes me wonder exactly what public service she is performing! For official Red Cross service uniforms, click here.

“Indoors or out, one could find many reasons why and times when just such a quaint smock and short skirt as [these] could be worn.” I don’t know what the editors of Ladies’ Home Journal were thinking, but the Red Cross did not allow women younger than 23 to serve coffee and doughnuts to the troops. They had their reasons. Although artistic, this leg-baring outfit might be subject to misinterpretation.