Collage of hats from Delineator, Sept. 1917, p. 62. These are not home made hats, but give an idea of the current styles.

Collage of hats from Delineator, Sept. 1917, p. 62. These are not home made hats, but give an idea of the wide range of styles.

I started to collect images of ladies’ hats from 1917, and discovered that I have far more material than I realized. The Ladies’ Home Journal ran a series of articles on home-made hats in 1917; women were encouraged to waste nothing, as part of the war effort. Similar make-your-own hat articles ran in September and November.

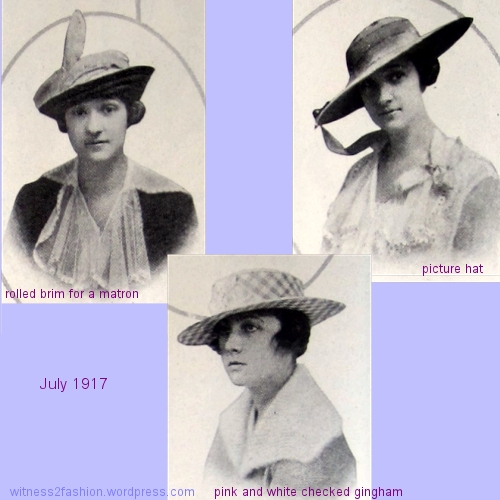

July 1917: Smart Hats From Ten-Cent Foundations

In July, women were encouraged to make their own hats as a patriotic duty: “As the call for recruits arouses the fighting spirit of the men, it also stirs the inherent thriftiness of the American girl to prove her preparedness to make many of her own clothes and fight the high cost of living.” [At Envisioning the American Dream, Sally Edelstein has been sharing wartime ads and posters aimed at the American woman in 1917. Click here for Part 1 of her series.]

Hats to make, Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1917. A rolled brim hat trimmed with bird wings for a married woman, a picture hat trimmed with tiny apples, and a pink and white gingham covered hat.

Notice the military phrase: “ready for active service in town or country.”

Hats to make, and a buckram frame foundation; Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1917. The hat on the right is a “mushroom hat” with braided straw under the brim.

“The frames on which the hats on this page are made are of light buckram like this [bottom center above,] and cost 10 cents each.” Several of these hats have cloth covering the frame on top, but their brims are “faced with straw.” The straw hat braid was bought by the yard and stitched together to fit the shape of the brim. Lynn McMasters shows how it’s done here.

A pre-formed hat frame or foundation like this can be ordered online, but it won’t cost ten cents any more. There’s a decent selection of wired, buckram frames at Hat Supply.com. You can buy wired brims separately.

These are the last two hats from the July article:

A pink linen sailor hat and a hat with a quilt-pieced crown. Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1917. The “quilt” hat’s brim –on the right — was faced with yellow [straw] braid.

September 1917: Hats You Can Make From Patterns

In September, The Ladies’ Home Journal wrote about “Hats You Can Make from Patterns.” The LHJ sold its own sewing patterns, but you had to write to the appropriate editor and ask for the pattern by number, enclosing a 4 cent stamp for each hat pattern.

“Hats You Can Make from Patterns” in Ladies’ Home Journal, September, 1917. Middle of page 85. Hairstyles were also illustrated. The hat in the center is a Tam.

The black velvet hat on the left is trimmed with tight spirals of white soutache braid.The black velvet hat on the right has a “top crown of white Georgette crepe, trimmed with a white worsted cockade.

Left: “In these war times, the designers cannot overlook the [military] fatigue-cap crown, as copied on this wide-brimmed hat of blue satin with appliqued red roses.” Right: A blue satin hat with a white satin facing, trimmed with a white tassel (which seems to be falling from the top of the crown.)

Left: “This is what may be done with red and blue ribbon and a national emblem.” Right: “Beaded pins still make a point of trimming smart hats, as you can see by this tall velvet-crowned, satin brimmed matron’s toque.” [A toque is defined as a hat without a brim. Fashion writing was as inconsistent 99 years ago as it is today.]

There was a strong military influence on women’s fashions during World War I. Pattern companies offered military insignia for trimming women’s dresses, hats and bags. The hats below were illustrated in Delineator magazine. Not only were the military cap (top left) and the shako (bottom right) popular, Napoleonic era bicorns and tricorns reappeared.

Women’s hats, Delineator pattern illustration, May, 1917. Military influence on women’s hats: An officer’s cap, a tricorn, and a shako.

Hats in fashion illustration, Ladies’ Home Journal, Nov. 1917. A shako at the left, a bicorn at the right.

The Ladies’ Home Journal also encouraged readers to make hats from unusual materials:

A hat made from the wool braid that used to be used for facing long skirt hems, and a hat covered with coarse-woven sacking. Ladies’ Home Journal. Sept. 1917. Pg. 84.

Fashionable women’s hats, Delineator, October 1917. These are not home-made, but the toques, tassel, asymmetrical rolled brim, and the shape at top left share some elements with the LHJ’s home-made hats.

Coming up: Part 2. In November, 1917, The Ladies’ Home Journal buys $25 hats and copies them for much less.