“If your hair grows so that a point can be made in the center of the back, have your barber cut it in a point.” — Celia Caroline Cole, in her article “Slicker ‘n’ Slicker,” Delineator magazine, January 1924.

I exerpted the first part of “Slicker ‘n’ Slicker” in Part 1 of this post. (Click here to read it.) (And thank you to Dinah and Cristina , et al, for their really informative comments!) If you watch Downton Abbey, you have probably seen the episode where Lady Mary gets her hair cut into a sleek bob with a point in the back. [After looking at many images from 1924 through 1925, I realized that the thick point above her nape was not what was bothering me; it was the length of her hair in front.]

Louise Brooks probably had the most iconic sleek bobbed hair in the movies (click here), but she didn’t have the pointed back shown in the illustration above, which, as Celia Cole says, was only possible for about one in fifty women. The really “slicker ‘n’ slicker” hair that “looks like paint” probably belonged to elegant Josephine Baker, the American girl who became a legendary star in France. (Click here.) She even marketed a hair preparation called “Bakerfix.”

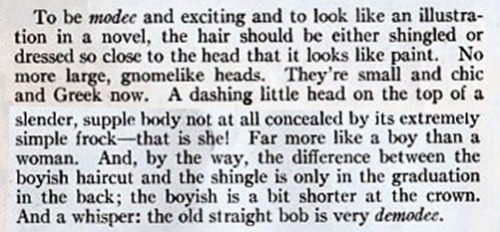

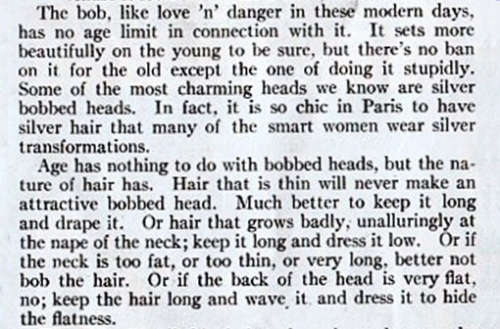

More from “Slicker ‘n’ Slicker,” January 1925

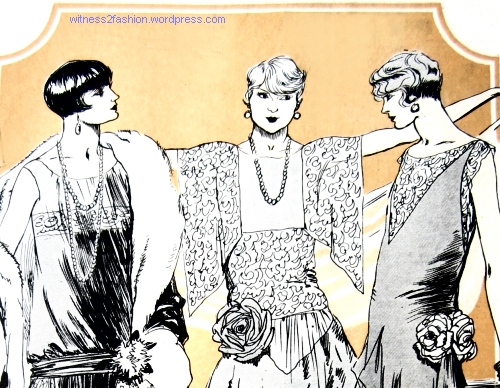

“The friendliest shingle is to have it cut long on the sides so as to cover the ears. . . . A lovely little sloping curve from behind the ear down to the sharp little point.” Two pattern illustration models from May, 1925. Butterick’s Delineator magazine.

“And long or short, the hair must be very neat — no more tousled heads — brushed until it shines, and for most faces waved in large, loose undulations.”

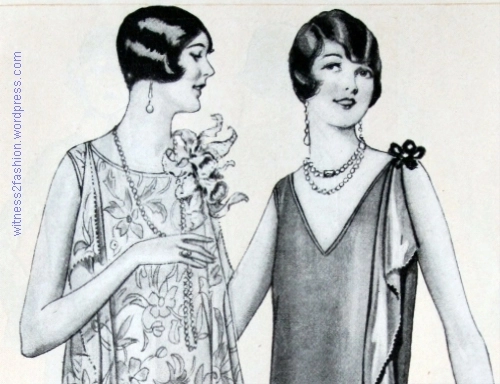

A Gallery of Mid-Twenties Hair Styles from Delineator Illustrations

A few months later, in January, 1925, the girl above left would have been among those who were advised to have the hair in back tapered or thinned “with a razor so that it does not stand out.”

The blonde on the right has her hair cut almost like a man’s, long in front and tapered in back. She has tendrils falling on her cheek, like these other Paris models:

Very short hair on Paris models. The two on the left are from January 1925; the one on the right is from April, 1924.

A haircut like this gave you the option of pulling a lock from the front down to curl on your cheek on each side, or you could brush it straight back, like singer Dora Stroeva, pictured in Delineator, March, 1924.

Singer Dora Stroeva wears a severely mannish “Eton crop” in the “New in New York” column; Delineator, March 1924.

The “Eton crop,” named after the prestigious English boys’ school Eton College, was the subject of cartoons like this one:

The woman on the right is admiring a photograph of the man the woman on the left is engaged to marry. March, 1928, Punch magazine, reprinted in The Way to Wear’em by Christina Walkley.

The caption says, “Young woman (looking at a photograph of friend’s fiance). ‘Well, God bless you, my dear, congratulations and all that. He certainly looks twice the man you are.’ ” (For more “fashion” cartoons from The Way to Wear’em and other books, click here.)

However, most women felt the need for some hair near the face to “save it from that utterly revealed look.”

1925, Delineator. The woman in the center has had her hair thinned a little at the bottom, as advised in “Slicker ‘n’ Slicker.”

Having some hair around the face looked better with a hat.

Hair Styles That Are “Nice to Buy Hats For”

“Any one who has had short hair knows the joy of it — cool and free, easy to care for and nice to buy hats for.”

Hats and hair, story illustration, September 1924. Delineator.

It’s hard now to remember that women once wore hats whenever they went out in public, but through the 1920’s and 1930’s photographs of crowds rarely show a person without a head covering of some kind. The tight-fitting, head-hugging hats of the 1920’s required hairstyles that could survive being compressed, and still look presentable when a woman took her hat off at work or at home. No wonder hairstyles got “slicker ‘n’ slicker.”

It didn’t matter whether the hat was a turban, or a cloche, or a hat with a brim; part of the twenties look is those little poufs or curls or “guiches” that fill in the hollow of the cheek. Without them, a cloche hides all your hair, and the look is austere and rather grim. As Celia Cole put it, ” The dressing of the hair means to the face and head what shrubbery and trees mean to a brand-new house: they save it from that utterly revealed look.”

Hats illustrated with dress patterns, February 1925. Delineator. Imagine how different they would look with no hair visible.

Even a tiny wisp of hair on the cheek softens the hat and sculpts the face.

Which brings me back to Lady Mary’s haircut. Because the front was longer than any of the styles shown in these 1924-1925 illustrations, her haircut didn’t work very well with the hat of her riding habit. Her hair didn’t fit neatly into the hollow of her cheek. It got messy. That bothered me, like getting a piece of popcorn stuck to a back tooth.

Of course, when it comes to dressing actors, the rule is , “The physical attractiveness of the actor to the audience outweighs all other considerations.” It doesn’t apply to all characters — and not to extras — but it does apply to leading actors playing physically attractive characters. Sometimes we search through incredible amounts of research, until we find one example that justifies the style that best becomes the actor. Molly Ivins said that there is nothing so dangerous as a man who has only read one book.” I probably haven’t found the right book — and “I’m always hungry for more.”