“Smart Patterns and Becoming Maternity Gowns,” from Good Housekeeping, February 1930, p. 74.

You’d expect fashion coverage from 1930 to be interesting, as women were trying to adjust to natural waistlines and descending hemlines. Caroline Gray, writing in Good Housekeeping, combined her suggestions for the mature figure with suggestions for maternity fashions. (Can you guess which are which?)

“The new silhouette is definitely here! Waists are higher and skirts are longer, and whether we like it or not, if we wish to look smart we must try to adapt it to ourselves and make it becoming…. Find the exact place where a higher belt is most becoming to you and put it there, regardless of whether it is quite as high as the dresses you see…. Nothing will look truly smart on you unless it suits your figure…. When you are determining the length of your skirt, experiment until you find the exact spot where it will add the most to your height and slenderness, for that is what we all want to achieve this season.”

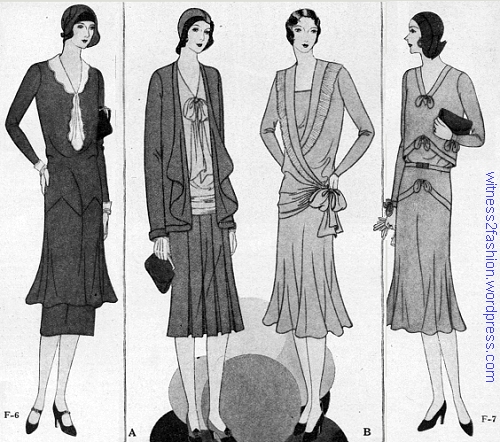

Good Housekeeping pattern F-7 was recommended in February 1930. Sizes 34 to 42. Not a maternity fashion.

“A small bolero is always becoming and makes the higher waistline more bearable.” The band at the hips echoes the familiar line of the twenties, but it follows the line of the bolero instead of running horizontally.

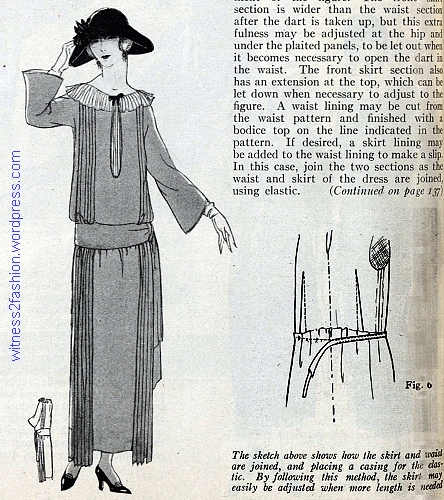

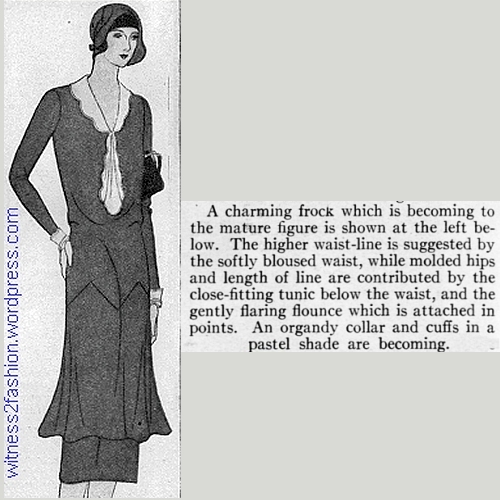

Pattern F-6 is also suggested as a transitional style for “mature” women:

Good Housekeeping pattern F-6 from February 1930, p. 74. The natural waist is fitted, but not accented. For sizes 36 to 42. The tunic gives both a short and a longer hemline.

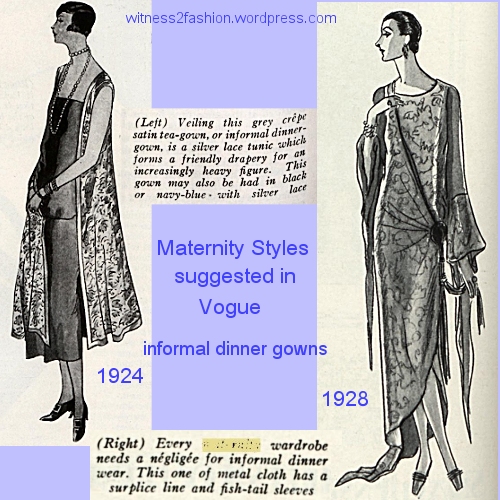

Of course, looking tall and thin is a challenge for most women even when they are not pregnant. Many writers in the 1920’s assumed that a woman’s goal was to conceal her pregnancy as long as possible.

“Maternity clothes have two objects: One is to make your condition unnoticeable, the other is to give you every physical advantage possible…. At this time you do not want to be conspicuous in any way.” — From The New Dressmaker, a Butterick book, c1921, p, 72.

To this end, Vogue suggested, in June of 1930, that pregnant women simply buy chic dresses in a larger-than-usual size, and have the neck and shoulders altered to fit.

“At first, concealment is easily effected by any woman with an eye for dress, but, after the figure is obviously changed, it is still possible to achieve, sometimes to the very end, the effect of a normal figure…. One should try to create the illusion of the naturally heavy figure, rather than be conspicuous for a disproportionate one.” — (Vogue, June 1930, pp 83, continued on p 102.) [This is 1930’s “pregnancy shaming:” it was better to be thought “heavy” than pregnant.]

Vogue suggested these fashionable gowns, among others, for the expectant mother in 1930:

Suggested maternity fashions, Vogue, June 1930. The one on the left was from Bonwit-Teller; the one on the right is a Vionnet tea-gown available from Jay Thorpe.

I’ll devote a later post to Vogue‘s other “just buy a bigger size” 1930 maternity suggestions.

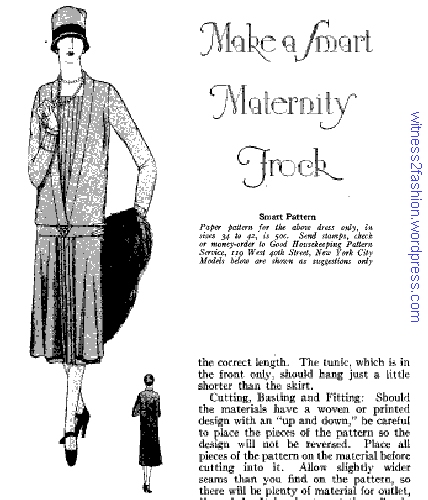

Here are the maternity styles suggested by Good Housekeeping in 1930:

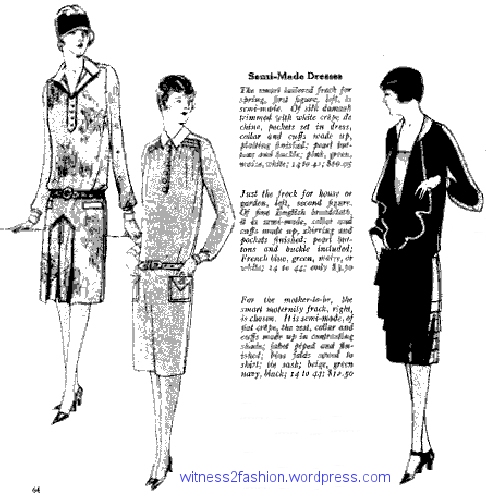

Maternity gown suggestions, Good Housekeeping, Feb. 1930, p. 74.

The article did not offer a pattern, or say that this suit and rather formal surplice dress could be purchased ready-made.

It’s hard to imagine how these dresses could be expanded enough, although the assumption was often made that you would constantly open seams, as your shape changed, and remake the dress as needed from wide seam allowances.

“It is much better to choose current styles that can be adapted to maternity wear and use them in preference to the special maternity clothes…. The slight alterations [!] that you make for maternity use can be changed back to normal lines after the baby is born.” (The New Dressmaker, circa 1921. Page 72.)

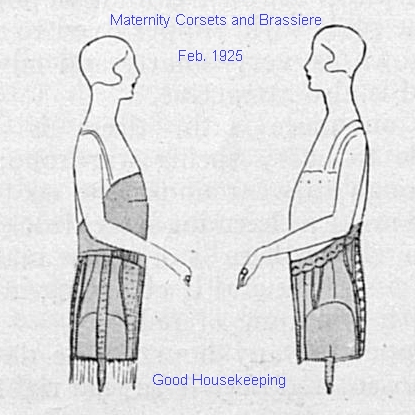

There Were Clothes Specifically for Pregnancy

Dressmaker Lena Bryant had found a market niche back in 1905, when her private clients began asking for maternity fashions (She used elastic in the waistbands, among other devices for making them expandable.)

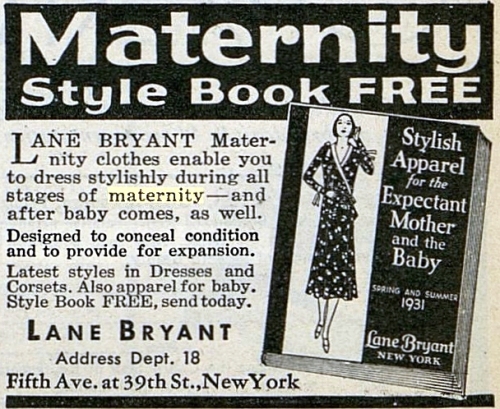

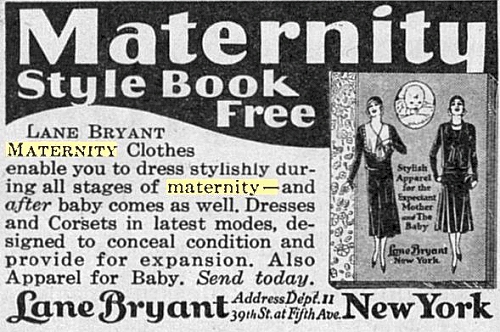

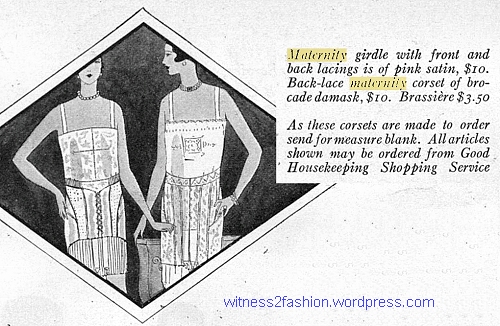

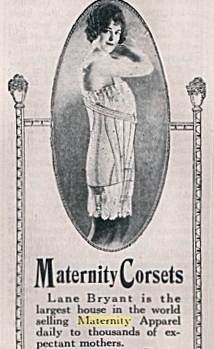

Lane Bryant ad for maternity corset, Ladies’ Home Journal, December 1917, p. 112.

“By 1904, [Lena] Bryant was successful enough to open her own shop on Fifth Avenue at 120th Street. In the process of obtaining a loan from Oriental Bank, her first name was misspelled, giving birth to “Lane Bryant.”

“Bryant soon turned to producing dresses as well as undergarments for pregnant women, who had a difficult time finding stylish clothes that fit well. Bryant designed a maternity tea dress, called “Number 5” after its place on the order form. According to Figure, no newspaper would run advertisements for her maternity dresses–it was against the mores of the day for “ladies in waiting” to appear in public. When Bryant finally managed to have a small ad run in the New York Herald, she sold out of maternity dresses the day it appeared.” — from Funding Universe (My McAfee security says it blocked ads from this site.)

Ad for the Lane Bryant maternity catalog, Delineator, March 1917. p. 43. “Portraying the prevailing New York fashions, but so adapted as to successfully conceal condition….Fit when figure is again normal.”

The Lane Bryant mail-order catalog passed $1 million in sales in 1917. (Oddly, that was an era that favored thick waists, very full skirts, and smock-type overblouses — one of the rare times when mainstream fashion was perfectly suited to accommodate pregnancy.) Lane Bryant promised that their dresses would “automatically adjust” to fit after the baby was born — making them a good investment.

Chanel styles, 1916, from Fashion Through Fashion Plates by Doris Langley Moore.

Teen-aged girls in California, circa 1918. Waists were thick (and high) and skirts were full.

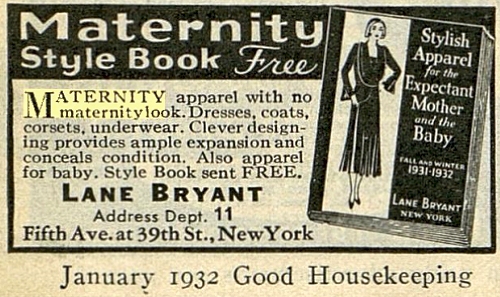

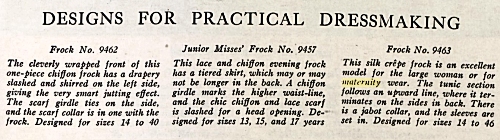

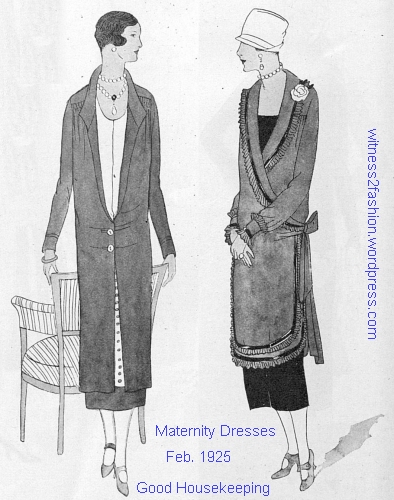

However, of the many decades when fashion was cruel to the chic pregnant woman, the early nineteen-thirties may hold the crown. These are maternity dresses. (Seriously.) The mores of the publishing industry meant that they could not be illustrated on a visibly pregnant body.

The illustration shows three versions of Companion-Butterick maternity dress pattern 6948, from Woman’s Home Companion, August, 1936. To read more about it, see Who Would Ever Guess?

A long, slender ideal silhouette plus soft, clinging fabrics, narrow hips, flat tummies, and (often) a decorative belt at the natural waist — combined with the idea that pregnancy was shameful and had to be concealed — must have made pregnant women feel frustrated in the thirties. Talk about an impossible ideal!