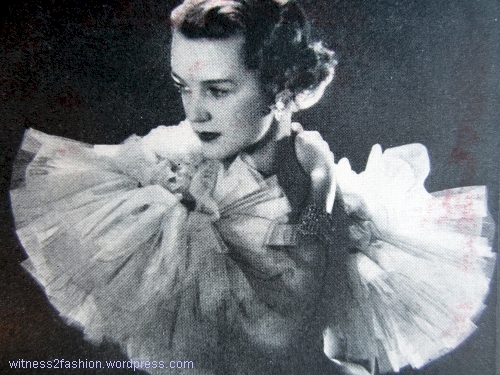

Butterick Patterns designed by Travis Banton for Helen Twelvetrees in Disgraced. Delineator, August 1933. “Below is the gown that brings forth all the ‘Oh’s’ and “Ah’s” when Miss Twelvetrees models it in ‘Disgraced.’ “

Today, costume designer Travis Banton is more remembered than actress Helen Twelvetrees. (No, that was not the name she was born with.) These patterns from August, 1933 are the last two Starred Patterns in the Butterick series that began in May of 1933. Butterick’s Delineator magazine had so much faith in this wedding gown design that it was the star of its own article a month later.

Disgraced is a Pre-Code melodrama. In it, Miss Twelvetree’s character, a fashion model named Gay, begins living with a rich wastrel in the belief that he will marry her. Instead, he plans to marry wealthy Julia, and Gay only discovers his plan when she has to model Julia’s wedding dress. Murder ensues. See the movie poster here.

Butterick pattern 5297, Delineator, August 1933. Designed by Travis Banton for the Paramount movie Disgraced.

The text of the article says that Butterick 5297 can be worn without the cape collar, but I’m afraid that the alternate view was not illustrated.

“Change-about” dresses were popular in the heart of the Great Depression.) Vintage Pattern Wikia has a larger image of this design, from the Fall 1933 Butterick catalog. The Delineator article was also printed in Butterick Fashion News.

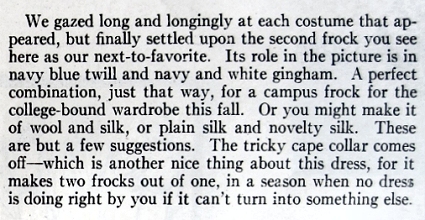

The wedding dress, Butterick 5299, was described in the Delineator in August:

“If, by any chance, you’re contemplating marriage, and you’re in the ususal dither about what to wear for the Big Moment, we urge you do do just one thing. Take yourself on the run to the nearest theater showing Helen Twelvetree’s latest picture, ‘Disgraced.’

“In this picture — in which there’s plenty of excitement besides the clothes, you can take our word for it — Miss Twelvetrees wears a wedding gown that is our idea of a wedding gown. It had us practically in a swoon. All that blond loveliness of course helped, but even a plainer girl, we imagine, would look pretty glamourous in such a gown. It’s a satin affair, with a yoke of fine net, and a tulle veil that is like a cape and quite the most lovely one we’ve seen in years of weddings, on- and off-stage. The idea is to wear it down, all around, until after the ceremony, and then to toss it back off the face for the recessional.” — Delineator, August 1933, p. 53.

Butterick Starred Pattern 5299, a wedding gown designed by Travis Banton for the movie Disgraced. Detail. Delineator, August, 1933.

There’s a larger image from the Butterick Fall catalog, 1933, at Vintage Pattern Wikia.

Travis Banton, Costume Designer

When you think of Marlene Dietrich in extravagant and improbable 1930’s costumes, you’re thinking of Travis Banton. They first worked together on Shanghai Express, in 1932. [Her most famous line from the movie is, “”It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.”] Click to see Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express (1932.)

“Travis did more than any single person to make Marlene Dietrich the clothes horse of the movies.” — Hedda Hopper, quoted in Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers, by Jorgensen and Scoggins.

Born in Waco, Texas, in 1894, Travis Banton grew up in New York. After serving in World War I, he worked for a custom fashion house, where he designed a lavish bridal gown which was seen by silent mega-star Mary Pickford. She wore it for her 1920 wedding to the equally famous Douglas Fairbanks. Banton remained in New York, working for top design house Lucile (Lady Duff-Gordon). He started his own salon, while also designing costumes for Broadway shows. He moved to California and signed a contract with Paramount Studios in 1925, where he worked happily (and often uncredited) for Chief Designer Howard Greer.

In 1927, Banton designed Clara Bow’s costumes for the movie It, a picture with plenty of advance publicity (or notoriety.) Here are several clips of Clara Bow in It, which must have inspired ambitious shop girls to try to look just like her. (Note that some of her 1927 costumes have natural waists….)

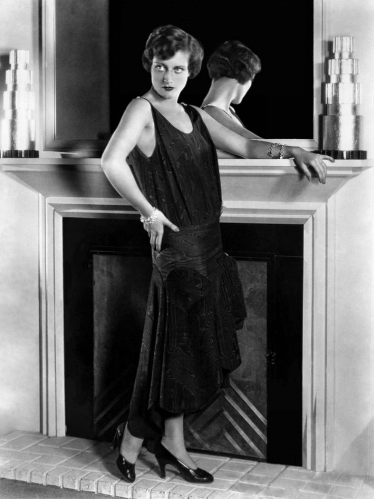

Marlene Dietrich in Angel, 1937. Costume by Travis Banton. Image from Creating the Illusion, by Jorgensen and Scoggins.

According to Creating the Illusion, Banton became known for form-fitting, lavishly embellished gowns. This heavily beaded dress for Marlene Dietrich in Angel (1937) cost the studio $8,000 ($135,000 in 2015 dollars.)

At the time, Banton’s salary was $1,250 per week. Paramount refused to increase it when his contract expired, so he left. [After watching a short commercial, you can see many more of his costumes from Angel at the IMDb site. Click here.]

Around 1940, Banton moved to 20th Century Fox, and in 1945 he moved to Universal. In the nineteen fifties he co-produced a clothing collection under the label “Marusia-Travis Banton.”

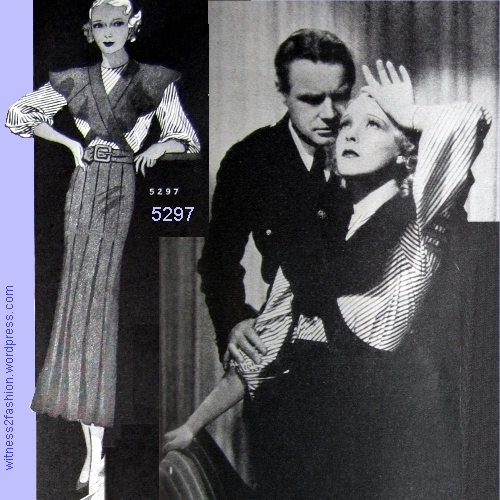

Carole Lombard in a beaded gown by Travis Banton. My Man Godfrey, 1936. Photo from Creating the Illusion.

The classic thirties comedy, My Man Godfrey (1936), featured Carole Lombard as a wealthy madcap in costumes by Travis Banton. [She wears this beaded outfit on a scavenger hunt to the city dump.] Here is that glittering gown in color.

If you have nine minutes to spare, this short film, “The Fashion Side of Hollywood”– which was made to publicize Travis Banton’s designs for several movies — is a treat. If you want to see a top model at work, watch the final segment; Marlene Dietrich poses in costumes that would look ridiculous on anyone else, and she looks wonderful. She clearly understood how to make the camera and lighting work for her!

This is the last of a series on Butterick Starred Patterns. Here are links to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.