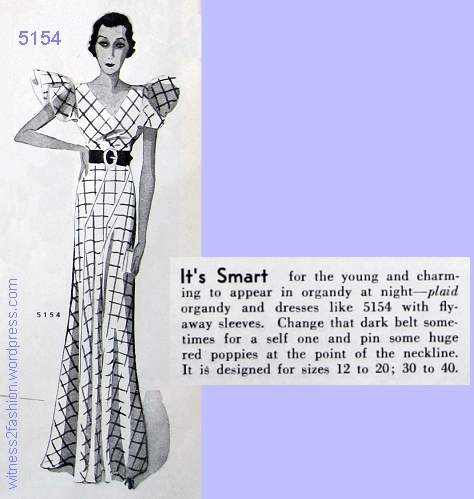

Part 1 of The Letty Lynton Dress, Adrian, and Joan Crawford’s Shoulders discussed one of the first movies Adrian designed for Joan Crawford: Letty Lynton (1932,) and its fashion influence. Here’s the Letty Lynton dress again:

Joan Crawford in “the Letty Lynton dress” designed by Gilbert Adrian. 1932. Image from Creating the Illusion, by Jorgensen and Scoggins.

The legend is that, because Joan Crawford had very broad shoulders, costume designer Gilbert Adrian decided to exaggerate them, instead of trying to distract us with styling tricks, and incidentally started the fashion for padded shoulders on women. And it is true that broad, padded shoulders for women came into fashion in the 1930’s and lasted through the World War II years.

Butterick Fashion Flyer, April 1938. Broad, padded shoulders for women — and impossible hips.

Butterick Fashion News, Sept. 1943. Broad, padded shoulders for women.

I’ve always been a little skeptical that Joan’s broad shoulders were ever a problem. This photo shows her in another evening dress from Letty Lynton.

Joan Crawford in another dress from Letty Lynton. Adrian often made bare-shouldered dresses for her. From Creating the Illusion.

You wouldn’t say she looks unattractive, or unfeminine…. In fact, she often wore costumes that bared her shoulders, like this one. from 1934.

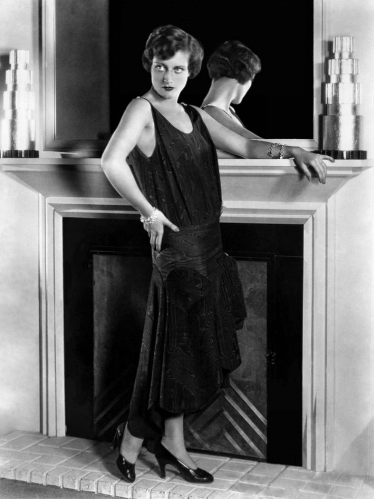

Here she is in the 1920’s:

Joan Crawford in the 1920’s. From Pinterest.

Crawford had been making movies since the 1920’s, and the truth is, if you want your hips to look smaller, it’s a good idea to make your shoulders look wider. (Or stand sideways….) A woman’s hips are not — in nature — inches narrower than her shoulders, although that is the way women were drawn in fashion illustrations from the twenties and thirties.

Fashion illustrations, July 1928. Delineator. Women don’t have hips that narrow.

Most women’s hips are as wide as, or wider than, their shoulders. Even Norma Shearer, “the Queen of MGM,” didn’t look fabulous photographed straight on in this twenties’ outfit.

Butterick fashion illustrations, Jan 1934. Delineator. Even wearing a really tight girdle will not make normal, childbearing hips that small.

The ruffled shoulders of the famous “Letty Lynton” dress are twice as wide as her hips. In this film clip, as Crawford is seen from the back, standing against a ship’s railing, her waist and hips look very narrow — like a fashion illustration.

Wide shoulders and full sleeves were also used to enhance the illusion of a tiny waist in the 1830’s and the 1890’s.

Wide shoulders and full sleeves create the illusion of a tiny waist, in 1832 and in 1895. Left Casey Collection; right, Metropolitan Museum.

The same “trick” reappeared in the 1980’s, to make waists and hips look smaller. Click here.

McCall’s bridal pattern 9452 (1985) and Vogue 9816 (1987). Full sleeves, wide shoulders.

I do believe another story that Adrian told — as quoted in Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers, by Jay Jorgensen and Donald L. Scoggins. They mention that Adrian designed the costumes for Joan Crawford in more than thirty-two movies, “…and in the process, created the padded-shoulder silhouette that defined the 1940s.”

“Crawford insisted on a free range of movement in her clothing. During fittings, she would rotate her shoulders with arms outstretched to ensure the fabric in her costumes could move with her. When Adrian was not designing in jersey or a fabric that stretched, he would let the clothes out across the back. He heavily padded Crawford’s shoulders to take up the slack in the fabric….” He said, “She is constantly in motion. When she is in the fitting room, she is always walking around, swinging her arms above her head to be sure she has freedom.” — Adrian, quoted in Creating the Illusion.

I’m certainly not in Adrian’s league, but I remember fitting an 1840’s bodice on an opera singer who kept crossing her arms in front of her body as far as possible, hunching her back, and popping the back of the muslin open.

“It fits all right, but I can’t do that!” she complained.

“Do you need to do that on stage?” I asked.

“Uh, no….” Luckily for me, she was a lot more reasonable than Joan Crawford.

Joan Crawford’s broad shoulders were probably an asset when she was wearing 1920’s styles.

Joan Crawford in the 1920’s. From Pinterest. If you want to look thin in a twenties’ dress, stand sideways.

Joan Crawford first rose to stardom playing a series of flappers in Our Dancing Daughters; Paris; Sally, Irene and Mary; The Taxi Dancer; The Duke Steps Out, and Our Modern Maidens. This video shows scenes from Our Dancing Daughters. (Also Pre-Code! note the panties, and her break-away skirt.) In 1932 she starred in Letty Lynton and in Rain (as Sadie Thompson , a prostitute with few illusions,) and appeared in Grand Hotel.

I admire her most in Grand Hotel . She plays a sympathetic role as a stenographer/part time prostitute trying to survive during the Depression. In this clip, she makes her situation clear to John Barrymore.

Crawford wore a “show biz” version of the Letty Lynton dress when she danced with Fred Astaire in Dancing Lady (1933). Here she is in another 1933 version of the Letty Lynton dress.

In this Hurrell photo, from 1934, you can see the padded shoulders on her evening gown. In 1937, her jacket is definitely padded like a man’s. The effect is even broader when done in fur: click here. Finally, here she is with Adrian, in 1939, and in Humoresque, 1946.

Most of these links are to a wonderful site: the photo gallery at joancrawfordbest.com. It’s well worth a visit, because Joan Crawford’s costumes were very influential in the mass market, and because — no matter what the style was, she could really wear a hat!