A little girl communicates with her “Paw Pa” through an ear trumpet. Family photo.

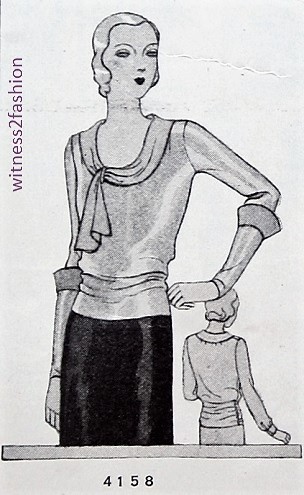

“Can you hear me now?”

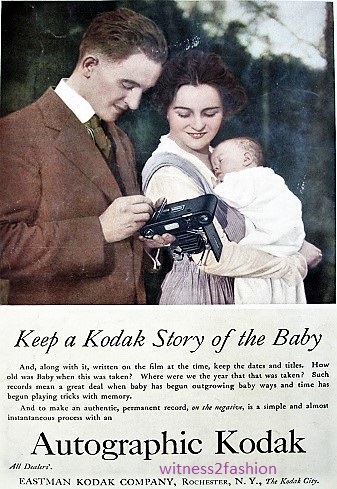

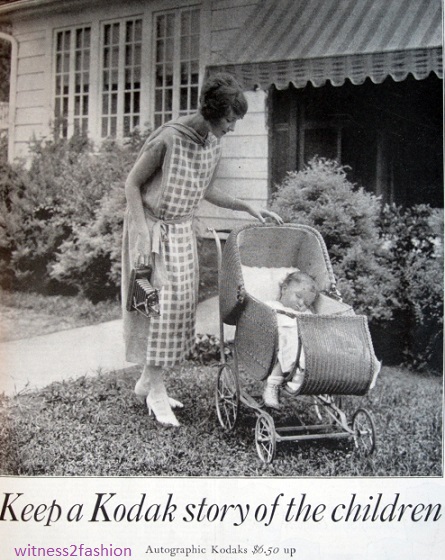

It’s time for my annual reminder to keep a box of unidentified family photos and an acid-free pen or a pencil at hand for the quiet moments at family gatherings.

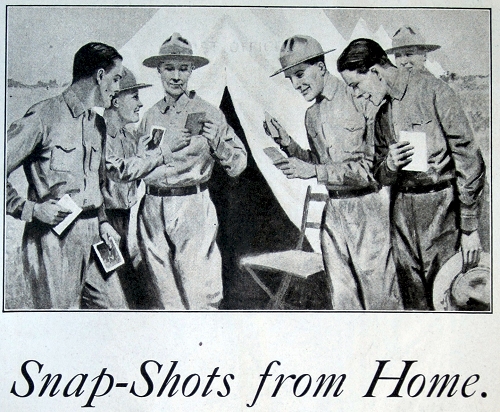

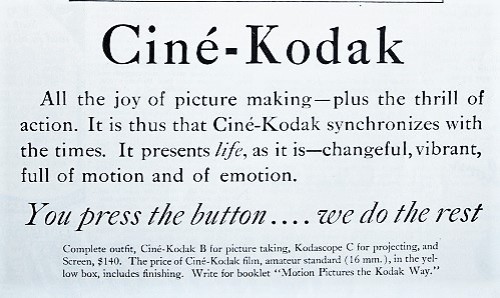

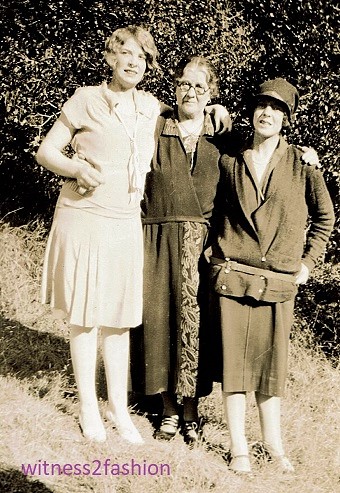

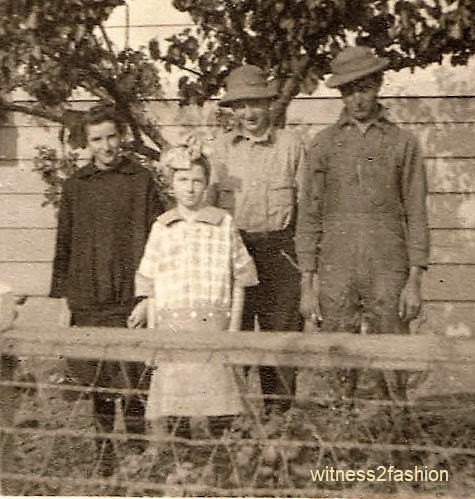

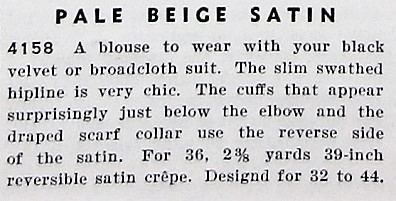

Gertrude, Mack, and Nina Holt with their mother “on her 70th birthday” (1938.) They lived in Pulaski, Tennessee, and sent this to their brother Leonard, in the Army in San Francisco. “I sure do wish Leonard was on here and then the 4 children and mother could all be together.”

Any time you gather with your eldest relatives and friends is a good time to chat about the past. Family stories need to be passed down. (Bonus: you won’t have to talk politics….)

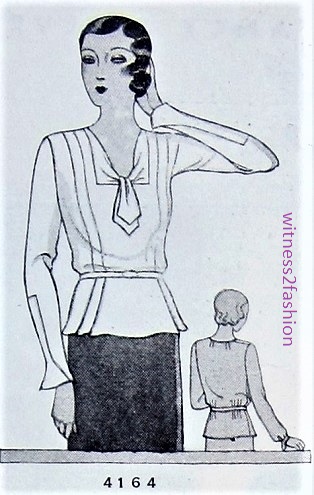

If you think you’ve heard all the stories before, consider that now that you are fully adult, seniors may be willing to tell you things they wouldn’t speak of when you were a child: failed marriages, lost loves, siblings who died young or were never mentioned for some other reason. (I certainly learned some surprising things when I asked as a adult!) Perhaps there is a terrific story behind one of those faces. Besides, sometimes the stories are funny — and just waiting to be told when the time is right.

Today’s photos come from a side of my family I never knew. My aunt Dorothy’s husband, Leonard H. Holt, died suddenly a short time before I was born.

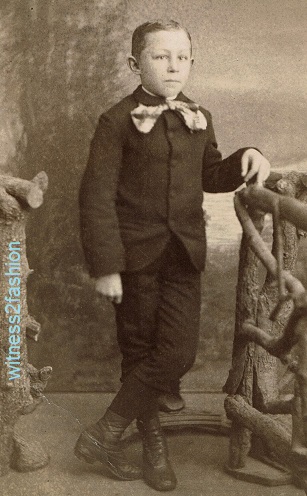

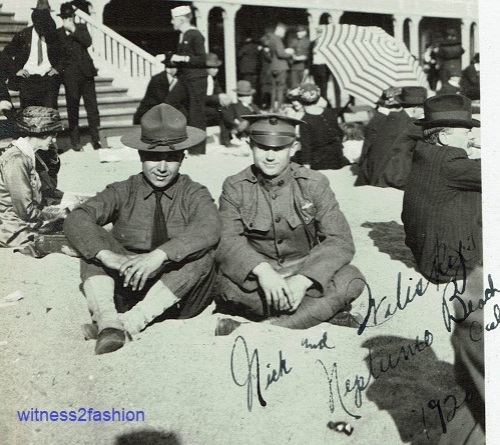

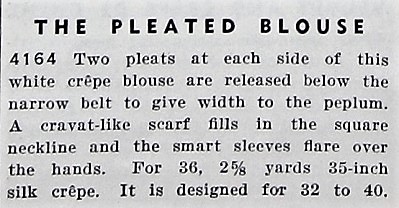

My uncle Leonard Holt, serving in World War II.

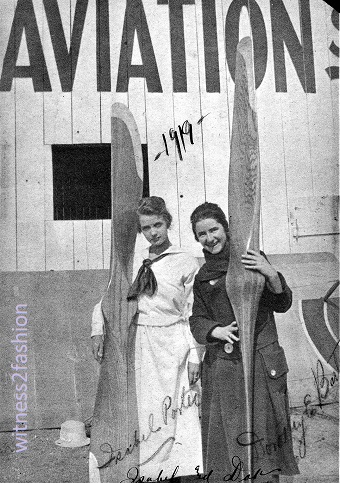

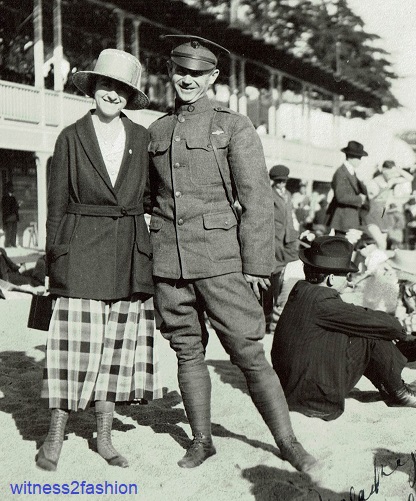

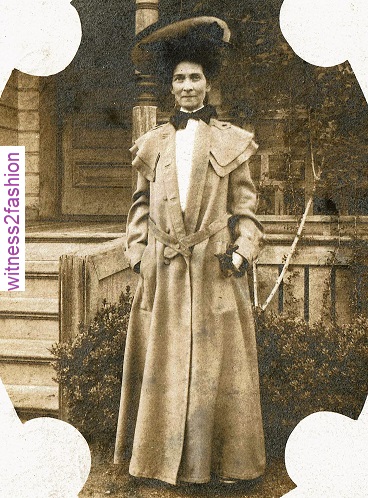

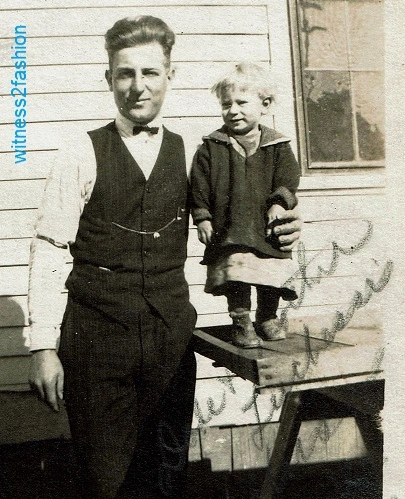

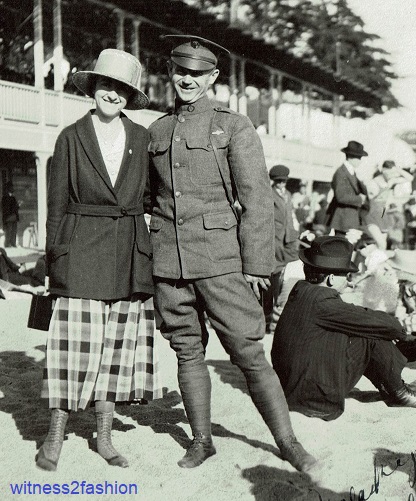

Dorothy, Holt, and Dorothy’s mother. Redwood City, CA, about 1919.

Dorothy is dressed in hiking clothes, and Holt is wearing “civvies” although he served at nearby Camp Fremont, an Army training camp during the First World War.

L. H. Holt standing in front of a Southern Pacific Railway building in San Francisco. Picture dated 1923.

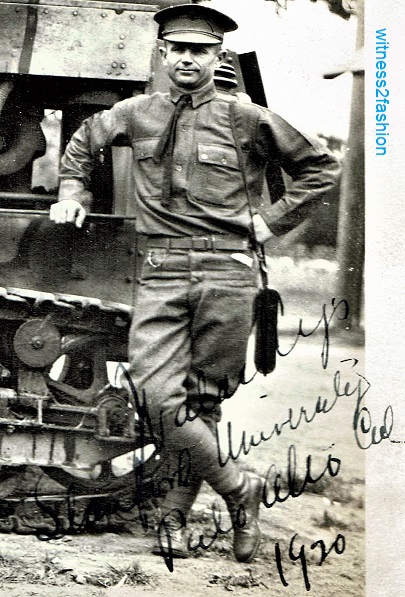

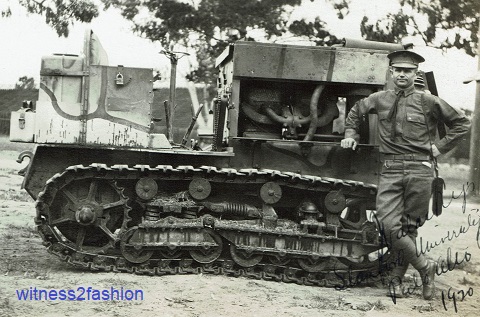

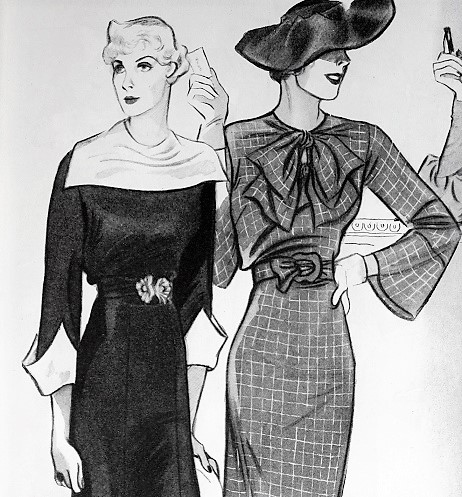

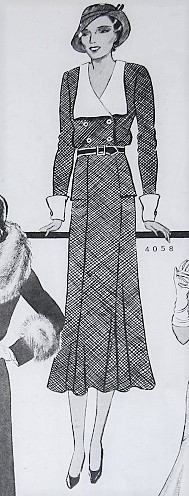

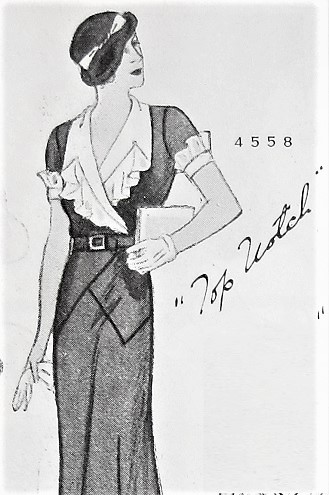

Dorothy did tell me that Holt was very particular about his clothes, and had his army uniforms tailored to fit well. Look at his elegant shoes! After Dorothy died, I found some of Holt’s silk shirts (with white French cuffs and made for a detachable collar) stored in the cedar chest that once held her wedding linens — a “hope chest” as unmarried girls called them. Holt’s shirts were beautiful, in soft pastel colors or stripes that epitomized the Arrow Shirt man’s look.

I think they were married about 1925. In 1930, Holt was still in the Army, and the couple lived on the Presidio, a beautiful Army base in San Francisco.

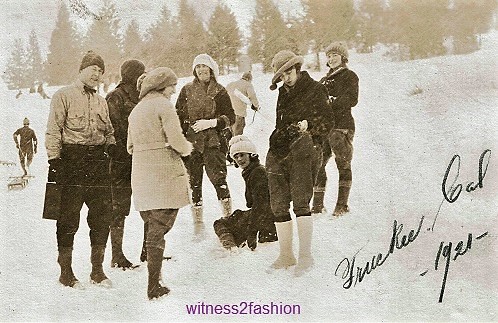

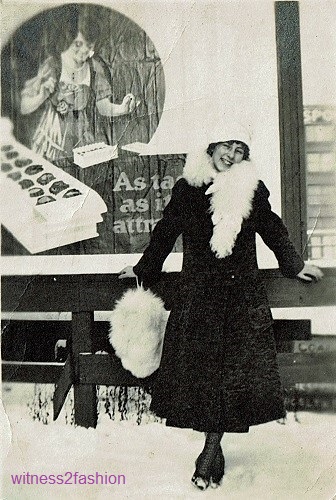

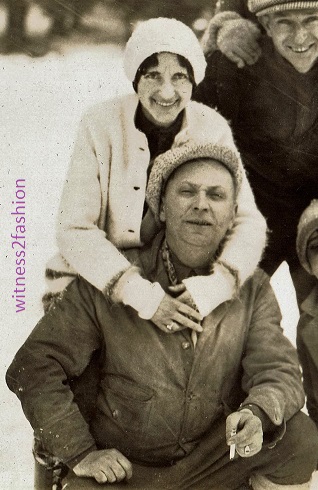

Dorothy and Holt vacationing in the snow, early 1930s.

In spite of war-time travel restrictions, Holt’s nephew (?) Jody Holt (serving in an Army band at the time) was visited by his sweetheart “Miss Meek” and his mother (?) Sally Holt, in San Francisco. 1945.

Holt died of a heart attack not long after this happy family visit.

Dorothy was so grief-stricken that she had a sort of breakdown, and didn’t speak of him very often, but she kept up a correspondence with his large family, including the Garners (his mother’s family) in Tennessee. In 1975, someone sent her a photo of the old family home on the farm:

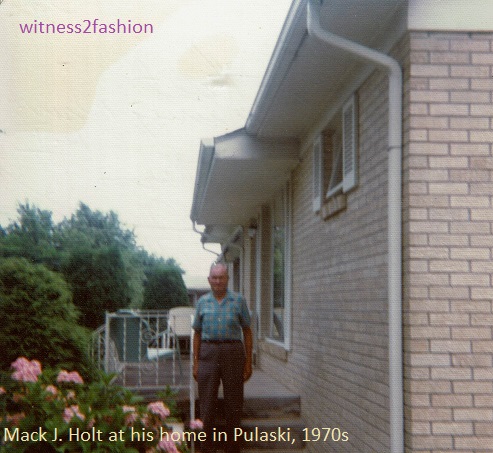

“The little old home on the farm, Pulaski, Tenn, Oct. 1975. Mack Holt’s Farm.”

Mack was still alive, and his new home was much larger.

Holt’s brother Mack apparently kept the old family farm, maintaining the tiny old farmhouse, and lived in a newer, larger house — a family success story. There is great information on the back of the photo, including “Mack J. Holt, Murry Drive” & “Leonard’s brother.”

The great thing about photos exchanged by mail is that they are often labeled or signed, including long notes on the back — a treasure for genealogists.

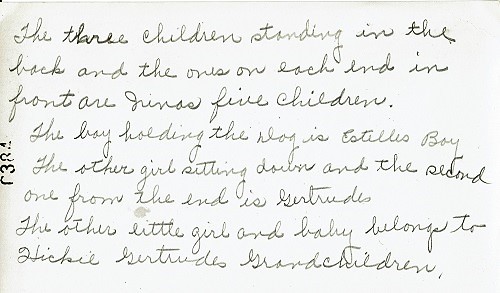

Many of these children are Leonard and Dorothy’s nieces and nephews. The back of the picture is full of information.

The back of a photo of many Holt family children. It tells us that Holt’s sister Nina had five children, and that his sister Gertrude had children (one called Hickie) and grandchildren. I don’t know who Estelle was, but that’s a trail to follow.

This photo gave me the names of Nina and Gertrude’s husbands: (Oddly, there’s another Mahlon in the family, her uncle….)

“Nina + Howard” and “Gertrude + Mahlon”

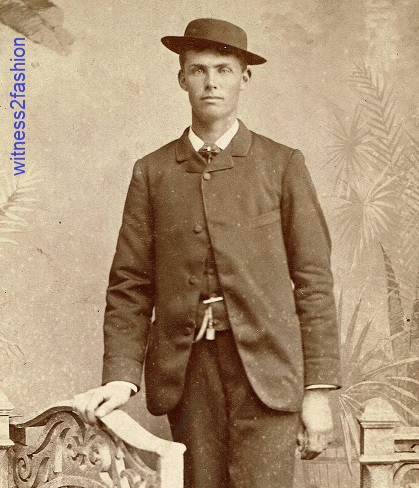

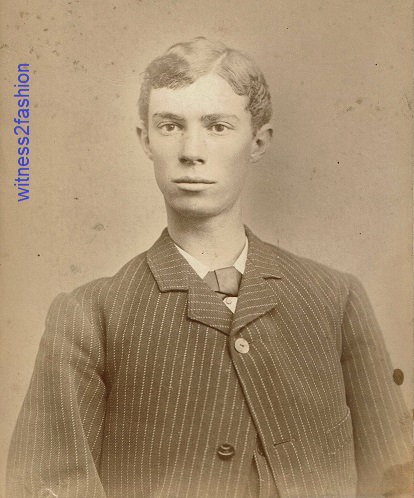

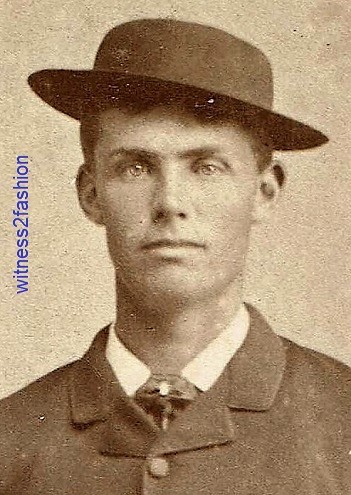

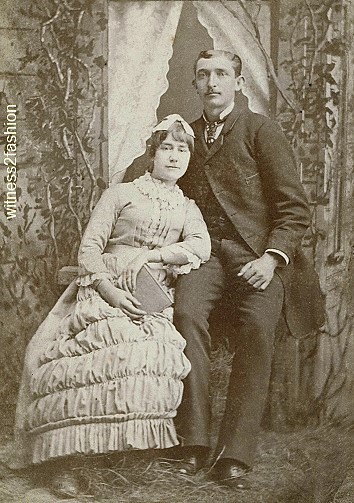

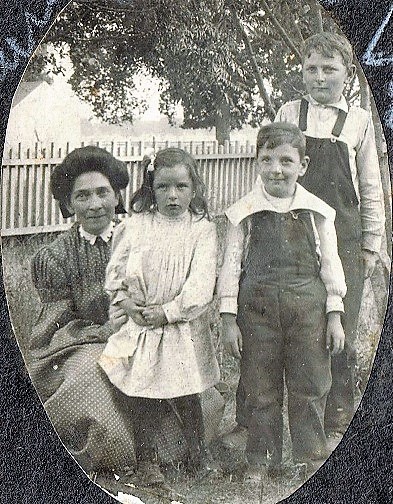

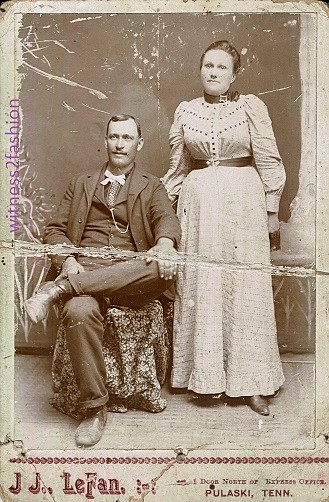

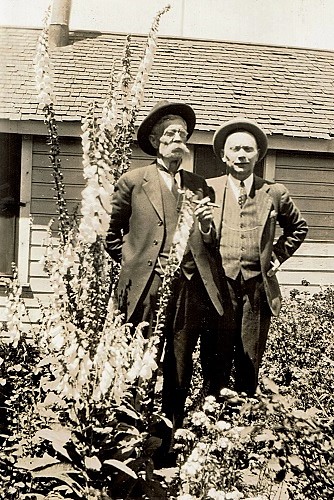

This photo is so old that is has cracked, but luckily the faces and their names are intact: “Leonard’ s Father The Holt Boys John & Mahlon Holt.” JH is on the right.

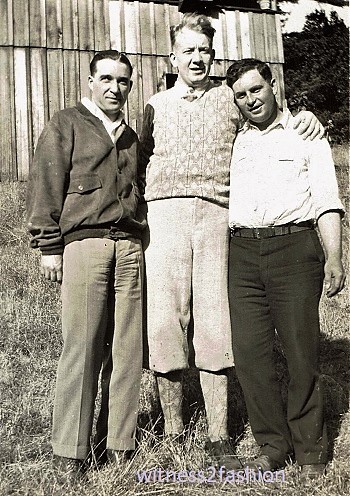

Unfortunately, not all the pictures mailed from Tennessee are labeled.

All I know about this couple is that they were photographed in Pulaski. Is this the same mustached man who appears far right in the large group photo below?

Perhaps there are folks in Pulaski, Tennessee, who will recognize their ancestors in this large, undated picture. (It’s 7.5 x 9″) I’d be happy to send it to someone who’d treasure it.

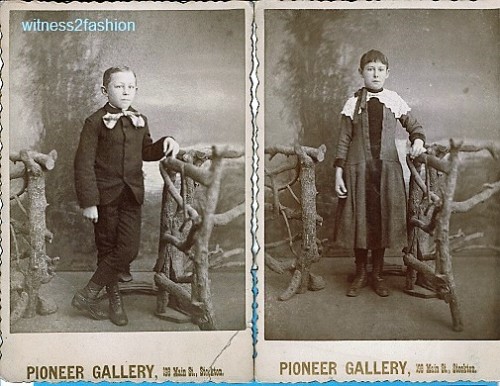

Studio photograph of the Holt family of Pulaski, Tennessee. There are no names on the back, but I think I recognize John Holt, standing 2nd from right, from another photograph. (He died in 1904.) I believe one of the young boys is Leonard H. Holt.

The woman seated center in this photograph appears to be wearing a mourning hat and black veil.

Detail of woman in widow’s cap.

Could the man seated in front, with a large mustache, possibly be this mystery man, photographed with both Holt and Dorothy, probably in the 1920s?

Unknown man with very large mustache, standing with Leonard H. Holt, probably at the Presidio in San Francisco, probably 1920s.

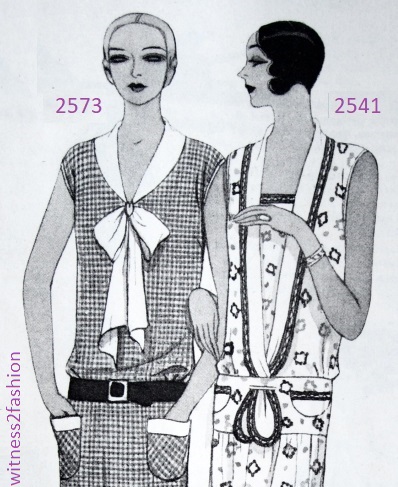

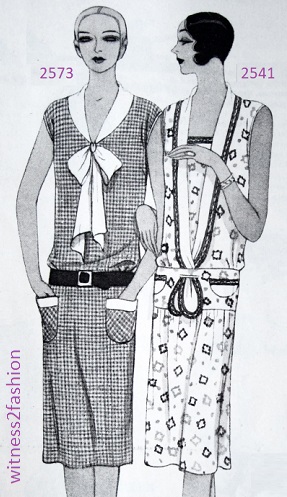

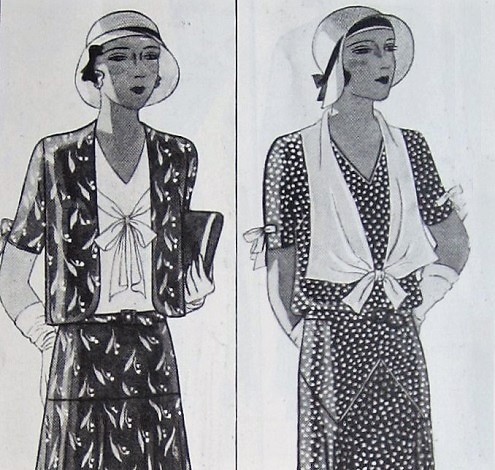

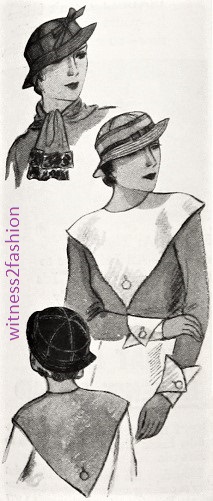

Mustached mystery man with Dorothy Barton Holt, probably at the Presidio in San Francisco, and, judging from her clothing, in the 1920s.

I believe this man was a visiting relative — there are many pictures of him. I could easily believe he’s from Tennessee….

[For any genealogist interested in the large group picture — or in any of these people, I believe these are relatives of Leonard H. Holt, born in Pulaski, Giles County, Tennessee on February 2, 1893 or (probably) 1894. His parents were John Richard Holt (1868-1904) and Metta Ann Garner (1868-1939). Their other children included Gertrude “Mamie” Holt (1893-1986), Katrina “Nina” Holt (1897 – ?), and McCallum “Mack” Holt (1900-?) My Uncle Holt (his wife never spoke of him by any other name) died of a heart attack while serving in California in 1945. At the time of his death, according to his wife, he held the rank of captain. They were childless. I think he was a Freemason, and Dorothy belonged to the Eastern Star — for those who can search such records. I have many photos of Holt family relatives, and no one to give them to.] You can contact me through witness2fashion@gmail.com

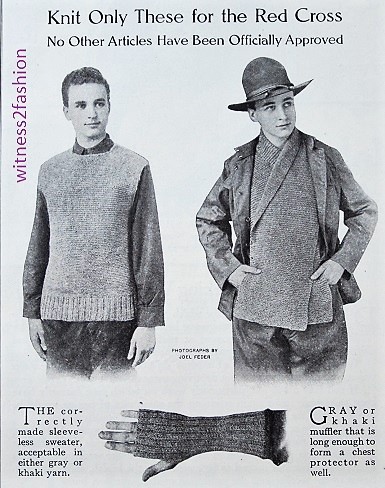

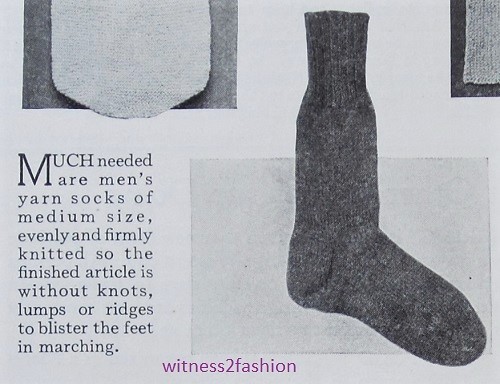

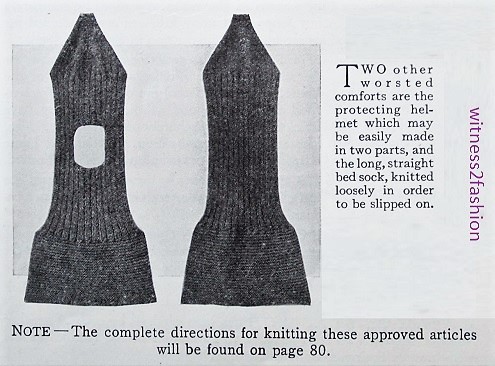

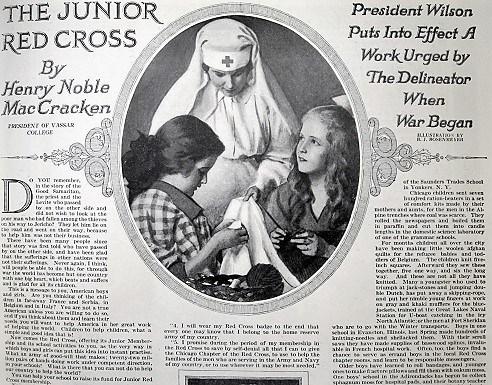

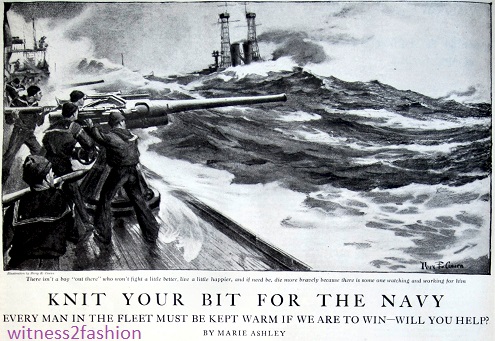

However, “In war more men die from exposure and illness than from wounds. Every hour that you waste, you are throwing away the life of one of our soldiers.” “Don’t say you are too busy to knit — it isn’t true.”

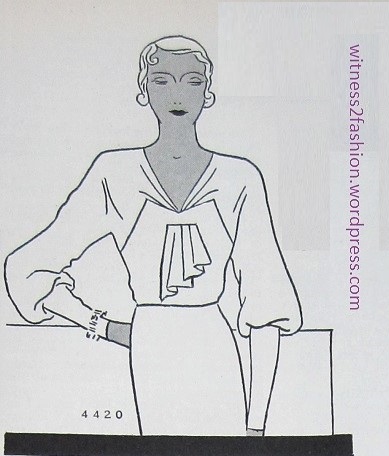

However, “In war more men die from exposure and illness than from wounds. Every hour that you waste, you are throwing away the life of one of our soldiers.” “Don’t say you are too busy to knit — it isn’t true.”